Voice referendum: What ‘No’ vote means for Closing the Gap targets

Voters said ‘No’ to the Voice, but the issues about Indigenous disadvantage will not go away. Here’s what experts say must happen now.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The emphatic victory of the ‘No’ case in the Voice to parliament referendum will require the government to perform a tricky double act, Sky News Chief Election Analyst Tom Connell says.

“They need to do two things. They need to be seen to immediately be getting on with everything else, around cost of living, childcare, housing, health, and show that (the referendum) is not something that’s paralysed them,” Mr Connell said.

But the Voice campaign has also raised so many issues around Indigenous disadvantage, and the government can’t be seen to walk away from those problems, he warned.

Proponents of the Voice had suggested it would enable real progress in closing the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

Its defeat means the government will be forced to find new ways to solve a host of complex, deep-seated problems.

LIFE EXPECTANCY

The gap in life expectancy between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians will remain one of the toughest issues for the government to fix.

The longstanding goal has been to close that life expectancy gap by 2032 at the latest, and while there has been some improvement, the differential remains stark: on average, Indigenous men die eight and a half years younger, and Indigenous women die almost eight years younger, than non-Indigenous Australians.

Throughout the Voice campaign Health Minister Mark Butler highlighted some of the specific health issues that affected Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, including the incidence of rheumatic heart disease (the world’s highest), and an increasing cancer mortality rate.

Stewart Sutherland, Associate Dean First Nations from the College of Health Medicine at ANU, said some advances had been made on closing the gap targets since the “Coalition of Peaks” (peak Aboriginal and Torrest Strait Islander organisations) started in 2020, and he hoped that would continue.

“If we go back to not listening to Aboriginal opinion we go back to what it used to be, and that is bad health for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people,” he said.

Voices at the state level could go some way to filling the void left by a national body, Mr Sutherland said, but the federal government could also look at the committees that advise senior ministers.

“What currently happens on both sides of politics is they are small groups, and [they’re] not always a group of experts,” he said.

“So if the government wanted to stop slippage (in Indigenous health) they could have broader groups … and have them expert focused.”

HEALTHY YOUTH

The gap in health starts from pregnancy.

Ninety-four per cent of non-Indigenous Australian babies are a healthy birth weight, but that proportion drops to 89 per cent for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander babies.

The Productivity Commission dashboard on Closing the Gap measures shows progress cannot be assumed, with NSW, the NT and the ACT all deemed to have gone backwards in this area between 2017 and 2020.

Mr Sutherland said some measures in this area were seeing success, including anti-smoking education for mums and increased support for first time mothers, and these should be continued.

Nicole Breeze, UNICEF Australia’s chief advocate for children, said Indigenous children “experience more disadvantage than many other children in Australia”.

“These challenges are not new, and they are not decreasing. We must keep working to address these disparities and ensure young Indigenous people are represented in this discussion,” she said.

FINISHING SCHOOL

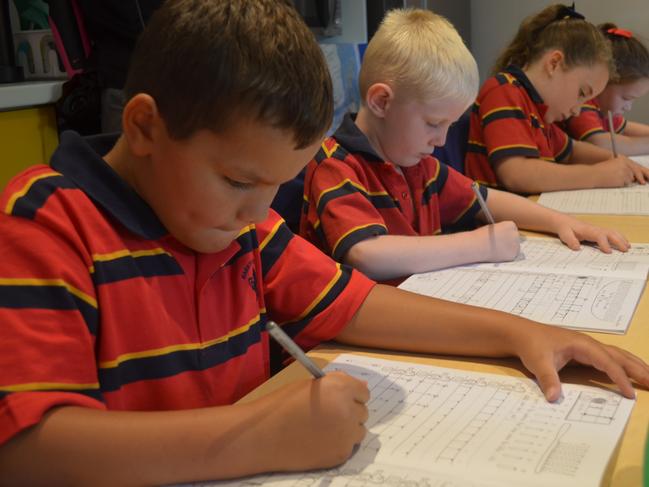

One area where progress has been made is the proportion of Indigenous kids finishing year 12.

In 2001, the rate was 40 per cent; in 2021 it was 68 per cent. While the growth is encouraging, it is still far off the rate for non-Indigenous Australians (nearly 91 per cent) and the 96 per cent goal set for 2031.

Australian Indigenous Education Foundation executive director Andrew Penfold said the government and private sector should fund projects that are evidence-based and have a proven track record, instead of wasting money.

His organisation offers children from low income Indigenous families scholarships to excellent boarding schools.

He said 93 per cent of kids on AIEF scholarships finish Year 12, and he has 17 years of data to prove what his organisation is doing works.

“We have kids from 400 different Indigenous communities that have graduated and gone on to be school teachers, engineers, business, owners, doctors and mechanics,” Mr Penfold said.

He said their success creates a ripple effect.

“We provide value for money for the taxpayer and have great retention rates,” Mr Penfold said.

“The government and the private sector should stop funding things that don’t work. They need to scale up funding for things that have proven track records.”

INCARCERATION RATES

The rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in prison are so shockingly high the issue was specifically referenced in the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017. “Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people,” the statement read.

Since then, the incarceration rates have climbed even higher.

In South Australia Indigenous people comprise almost a quarter (24 per cent) of the total prison population, while 60 per cent of Australian children in youth detention are Indigenous.

More than 120 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander organisations believe the way to reduce incarceration rates is to raise the age of criminal responsibility to 14.

Change the Record is one of the groups supporting the campaign.

Executive officer Maggie Munn said recently: “(We are) incarcerating children who don’t understand the gravity of their behaviour, and then wondering why that behaviour doesn’t change”.

“Children belong in schools and playgrounds and need to be supported to learn from their mistakes, not locked in cages,” Ms Munn said.

“The evidence on what works is abundantly clear: we need to fund culturally safe, trauma-informed, therapeutic, and non-punitive programs and services that keep children out of the legal system.”

COMMUNICATING WITH INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS

Advocates for the Yes case expressed hope the defeat of the Voice to parliament proposal would not silence Indigenous Australians.

During the referendum campaign, both Labor and the Coalition expressed support for the concept of “regional voices” – but as to how they would be administered, or function, there has been little detail.

THE REPUBLIC

The referendum result has prompted many to suggest it could also spell the end for the republic as well, with commentators suggesting the government is unlikely to want to anchor itself to another costly, time-consuming vote during the next term of parliament.

“When (the Voice) referendum was contemplated there was support up around 60 per cent, and now it’s failed,” Connell said.

“Republic support right now on published polling is around 50 per cent, so you’ve got something where it starts out a lot less popular and then it somehow has to survive the weight of the referendum process.”

The Voice result reinforced the idea that referendums need bipartisan support to succeed, Mr Connell said – so if the Coalition did not back a proposal for a republic referendum, there was little point proceeding with one.

But Australian Republic Movement CEO Isaac Jeffrey differed, saying the “no vote for the Voice, isn’t a setback for the republic, it’s a setback for the Voice”.

“Only 8 per cent of the country are rusted on monarchy supporters, meaning 92 per cent are either supportive of becoming a republic or are open to it,” he said.

“We will be working with the parliament to hold a new republic referendum – hopefully in the next term.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Voice referendum: What ‘No’ vote means for Closing the Gap targets