Migrant dreams of freedom under threat as anti-Semitism surges in Australia

Jewish migrants abandoned former lives in Europe, the Middle East and Africa for the promise of freedom offered by Australia. But now that precious sense of freedom is under threat as anti-Semitism surges.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Alex Ryvchin’s family fled the crushing oppression of the former Soviet Union for the expansive waters of Sydney’s eastern suburbs.

Dr Ivan Goldberg AM has devoted his life to medicine after sailing into Sydney Harbour following a five-week voyage to escape the racism of South Africa.

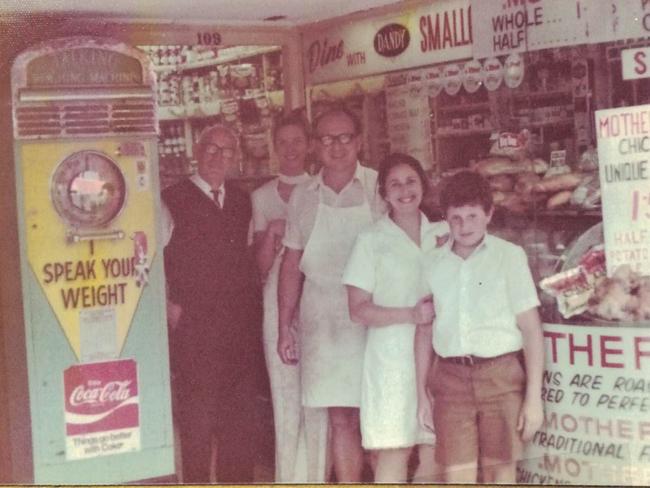

Journalist Michael Visontay’s family ran a thriving delicatessen amid the debauchery of Kings Cross after the family business was twice seized in Hungary, first by Nazis and then by communists.

And academic Dr Anita Frayman’s late father survived the unimaginable horrors of the Holocaust to arrive in Melbourne, orphaned but resilient, to live a good life until the ripe age of 94.

They are just some of the countless Jewish migrants whose families abandoned former lives in Europe, the Middle East and Africa for the promise of freedom offered by Australia.

Among them are billionaires including Meriton founder Harry Triguboff and Westfield founder Frank Lowy, former governor-general Isaac Isaacs and Josh Frydenberg, the nation’s first Jewish treasurer.

But that precious sense of freedom is now under threat as anti-Semitism surges amid the ongoing war between Israel and Hamas, a conflict more than 14,000km away that nonetheless has fractured Australian society.

Mr Ryvchin, co-chief executive of the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, said the reaction in Australia to the ongoing war had robbed many Jewish Australians of their faith in the nation they loved.

“I think the greatness of our community is we contribute to wider society, we’re part of wider society,” he says.

“That’s how we’ve always viewed ourselves. So I’m a bit fearful that because of the backlash we’ve received, because of the hatred we’ve seen, we’ve become a bit more tribal and insular and I think we need to overcome that.”

Hamas terrorists stormed the Nova Music festival in southern Israel on October 7 last year, killing 1200 people and kidnapping 250.

The Palestinian militant group has yet to release 60 living hostages and the bodies of 35 others, one of Israel’s conditions for a ceasefire.

Journalist and author Michael Visontay, 65, said dismay at the reaction, or lack thereof, by wider Australia darkly coloured the months following the October 7 attacks as the Jewish community faced increased hostility.

“That lack of compassion for what happened to Israeli people on October 7 was sort of the flame that lit our insecurity,” says Visontay, who has just published novel Noble Fragments about his family’s migration experience.

“We were expecting that there would have been an outpouring of compassion and solidarity. And when there wasn’t, we were shocked. And nobody’s really forgotten that.”

Mr Visontay’s father Ivan came to Australia in 1952 from Hungary, then under communist rule, after he survived a concentration camp to start a delicatessen in King’s Cross.

Both the communists and the Nazis had at different times confiscated the family delicatessen. The second time the business was stolen was the final discriminatory straw for the Jewish family.

“They [the Visontays] were able to have a good and secure life in Australia, have their own home, socialise with friends, raise a family and feel that they would be able to do that without any fear of the government turning against them,” said Mr Visontay, who is the commissioning editor of The Jewish Independent.

Last week Australia backed a United Nations resolution to recognise the “permanent sovereignty” of Palestinians after 20 years of voting against or abstaining from voting on the resolution.

It followed violent clashes between pro-Palestinian protesters and supporters of Israeli football team Maccabi Tel Aviv in Amsterdam that shocked the world and unleashed months of local tension over the war in the Middle East.

University of Sydney emeritus professor Suzanne Rutland, who has devoted her life to the study of Jewish migration, said after WWII most Jews wanted to escape Europe as soon as possible and said there were close to 120,000 Jews currently in Australia.

“Europe for them was a graveyard and they just applied everywhere,” she says.

“Of course they couldn’t immediately get to Israel because Israel as a separate country was only created on November 29 in 1947.”

Professor Rutland said survivors often worked very hard after arriving in their new country and created amazing success stories such as Mr Lowy and the late John Saunders, who co-founded Westfield.

“It’s very much a Jewish story that Jews want to work hard, they want to contribute to the country if they have freedom, if they’re accepted as equals – as Australia has offered all of us who are Jewish that chance,” she says.

Dr Ivan Goldberg, 77, was awarded Member of the Order of Australia for services to medicine, particularly in the field of ophthalmology.

At about 6am one morning in 1962 he and his family sailed into Dawes Point at what is now the site of the Sydney Theatre Company’s Wharf Theatre after a five-week voyage from Cape Town.

“As we came down into the harbour, the mist lifted and we could see the harbour for what it was – absolutely magnificent,” he says.

“We came under the [Sydney Harbour] bridge and docked, and then we were all part of this group of people getting off with all our suitcases and things.

“It was a very exciting day, the beginning of a new life for us.”

Increasing racism in South Africa prompted Dr Goldberg’s family to abandon their former lives, leaving stable jobs and a house behind in Johannesburg.

But in Australia the family found an open and welcoming nation with a lifestyle similar to South Africa but without the underlying racial discrimination.

Dr Goldberg has family in Israel and has been shocked by surging anti-Semitism in Australia as well as a lack of condemnation from political and institutional leaders.

Nonetheless he says he still believes in Australia although he says the Jewish community has learnt they have to empower themselves and fight their own battles.

“I haven’t lost faith in the country,” he says.

Monash University’s Australian Centre for Jewish Civilisation director David Slucki says the Jewish community has not always been welcome in Australia but said it became more difficult to be publicly anti-Semitic after WWII.

“Anti-Semitism became less visible in a way but it never really abated,” he says.

“So what we’ve seen lately in terms of rising anti-Semitism, a lot of people think well maybe what we’re seeing has been under the surface and it’s sort of rearing its ugly head again.”

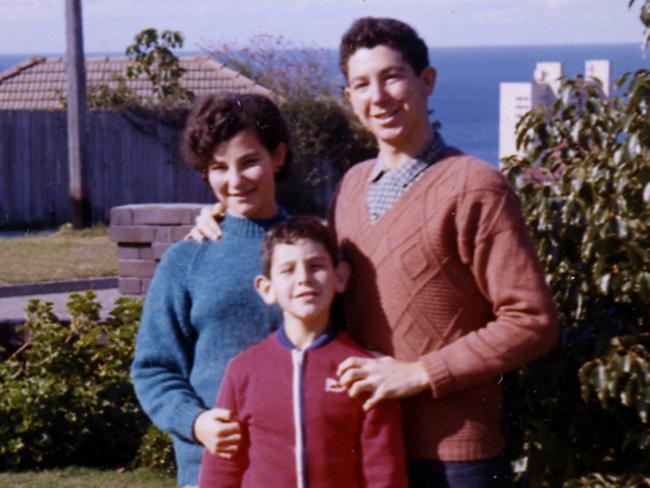

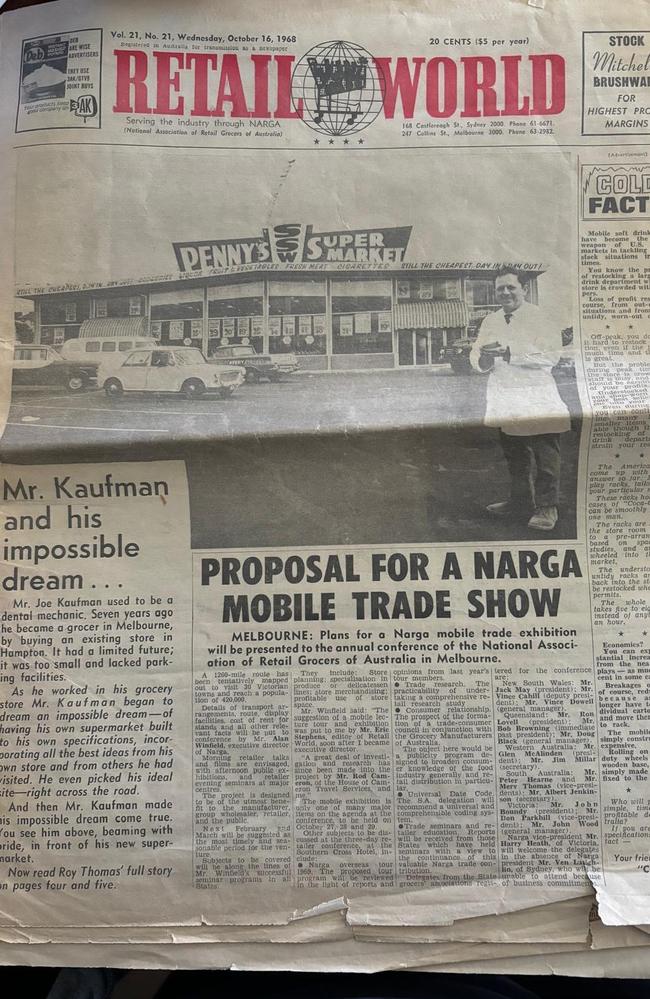

Dr Anita Frayman’s late father Joe Kaufman opened a supermarket in the Melbourne bayside suburb of Hampton after surviving the notorious Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany.

He was one of about 65 survivors who came to Australia, with the group eventually earning the moniker of Buchenwald Boys as they helped other Jewish migrants resettle into Australia.

“They [Buchenwald Boys] thought they were so fortunate to be in Australia,” says Dr Frayman, who has interviewed many of the group as part of her work.

“They loved every minute they were here … They thought Australia was just a marvellous country that treated them all really well.”

The Buchenwald Boys will celebrate the 80th anniversary of their liberation and their new lives in Australia at a ball in Melbourne next year.