Full Uluru Statement: Read the entire document about the Voice

Read the entire Uluru Statement from the Heart and decide for yourself what you think about its agenda for Australia and reconciliation.

Since July debate has raged over the length of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, and whether it is a one page document or something much longer.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and other Voice to Parliament supporters point to the first page and call it a “simple and gracious” request.

Opponents of the Voice say that the longer document is divisive and reveals a much bigger agenda including treaty and reparations.

Below, we have reproduced the entire text of the longer version of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, which was revealed in the results of a Freedom of Information request to the National Indigenous Australians Agency, so you can read the whole thing and make up your own mind.

See the full statement below:

ULURU STATEMENT FROM THE HEART

We, gathered at the 2017 National Constitutional Convention, coming from all points of the southern sky, make this statement from the heart: Our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander tribes were the first sovereign Nations of the Australian continent and its adjacent islands, and possessed it under our own laws and customs.

This our ancestors did, according to the reckoning of our culture, from the Creation, according to the common law from ‘time immemorial’, and according to science more than 60,000 years ago. This sovereignty is a spiritual notion: the ancestral tie between the land, or ‘mother nature’, and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples who were born therefrom, remain attached thereto, and must one day return thither to be united with our ancestors.

This link is the basis of the ownership of the soil, or better, of sovereignty. It has never been ceded or extinguished, and coexists with the sovereignty of the Crown. How could it be otherwise?

That peoples possessed a land for sixty millennia and this sacred link disappears from world history in merely the last two hundred years? With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this ancient sovereignty can shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

Proportionally, we are the most incarcerated people on the planet. We are not an innately criminal people.

Our children are alienated from their families at unprecedented rates. This cannot be because we have no love for them. And our youth languish in detention in obscene numbers. They should be our hope for the future.

These dimensions of our crisis tell plainly the structural nature of our problem. This is the torment of our powerlessness. We seek constitutional reforms to empower our people and take a rightful place in our own country.

When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish. They will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country. We call for the establishment of a First Nations Voice enshrined in the Constitution.

Makarrata is the culmination of our agenda: the coming together after a struggle. It captures our aspirations for a fair and truthful relationship with the people of Australia and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

We seek a Makarrata Commission to supervise a process of agreement-making between governments and First Nations and truth-telling about our history. In 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard.

We leave base camp and start our trek across this vast country. We invite you to walk with us in a movement of the Australian people for a better future.

OUR STORY

Our First Nations are extraordinarily diverse cultures, living in an astounding array of environments, multilingual across many hundreds of languages and dialects.

The continent was occupied by our people and the footprints of our ancestors traversed the entire landscape. Our songlines covered vast distances, uniting peoples in shared stories and religion. The entire land and seascape is named, and the cultural memory of our old people is written there.

This rich diversity of our origins was eventually ruptured by colonisation. Violent dispossession and the struggle to survive a relentless inhumanity has marked our common history. The First Nations Regional Dialogues on constitutional reform bore witness to our shared stories. All stories start with our Law.

The Law

We have coexisted as First Nations on this land for at least 60,000 years. Our sovereignty preexisted the Australian state and has survived it.

‘We have never, ever ceded our sovereignty.’ (Sydney)

The unfinished business of Australia’s nationhood includes recognising the ancient jurisdictions of First Nations law.

‘The connection between language, the culture, the land and the enduring nature of Aboriginal law is fundamental to any consideration of constitutional recognition.’ (Ross River)

Every First Nation has its own word for The Law. Tjukurrpa is the Aṉangu word for The Law. The Meriam people of Mer refer to Malo’s Law. 5 With substantive constitutional change and structural reform, we believe this surviving and underlying First Nation sovereignty can more effectively and powerfully shine through as a fuller expression of Australia’s nationhood.

The Law was violated by the coming of the British to Australia. This truth needs to be told.

Invasion

Australia was not a settlement and it was not a discovery. It was an invasion.

‘Cook did not discover us, because we saw him. We were telling each other with smoke, yet in his diary, he said “discovered”.’ (Torres Strait)

‘Australia must acknowledge its history, its true history. Not Captain Cook. What happened all across Australia: the massacres and the wars. If that were taught in schools, we might have one nation, where we are all together.’ (Darwin)

The invasion that started at Botany Bay is the origin of the fundamental grievance between the old and new Australians: that Australia was colonised without the consent of its rightful owners.

Now is an opportunity for the First Nations to tell the truth about history in our own voices and from our own point of view.

And for mainstream Australians to hear those voices and to reconsider what they know and understand about their nation’s history. This will be challenging, but the truth about invasion needs to be told.

‘In order for meaningful change to happen, Australian society generally needs to “work on itself” and to know the truth of its own history.’ (Brisbane)

‘People repeatedly emphasised the need for truth and justice, and for non-Aboriginal Australians to take responsibility for that history and this legacy it has created: “Government needs to be told the truth of how people got to there. They need to admit to that and sort it out. “’ (Melbourne)

Invasion was met with resistance.

Resistance

This is the time of the Frontier Wars, when massacres, disease and poison decimated First Nations, even as they fought a guerrilla war of resistance. The Tasmanian Genocide and the Black War waged by the colonists reveals the truth about this evil time.

We acknowledge the resistance of the remaining First Nations people in Tasmania who survived the onslaught.

‘A statement should recognise “the fights of our old people”.’ (Hobart)

Everywhere across Australia, great warriors like Pemulwuy and Jandamarra led resistance against the British.

First Nations refused to acquiesce to dispossession and fought for their sovereign rights and their land.

‘The people who worked as stockmen for no pay, who have survived a history full of massacres and pain. We deserve respect.’ (Broome)

The Crown had made promises when it colonised Australia. In 1768, Captain Cook was instructed to take possession ‘with the consent of the natives’.

In 1787, Governor Phillip was instructed to treat the First Nations with ‘amity and kindness’. But there was a lack of good faith.

The frontier continued to move outwards and the promises were broken in the refusal to negotiate and the violence of colonisation.

‘We were already recognised through the Letters Patent and the Imperial statutes that should be adhered to under their law. Because it’s their law.’ (Adelaide)

‘Participants expressed disgust about a statue of John McDougall Stuart being erected in Alice Springs following the 150th anniversary of his successful attempt to reach the top end. This expedition led to the opening up of the “South Australian frontier” which lead to massacres as the telegraph line was established and white settlers moved into the region. People feel sad whenever they see the statue; its presence and the fact that Stuart is holding a gun is disrespectful to the Aboriginal community who are descendants of the families slaughtered during the massacres throughout Central Australia.’ (Ross River)

Mourning Eventually the Frontier Wars came to an end. As the violence subsided, governments employed new policies of control and discrimination.

We were herded to missions and reserves on the fringes of white society. 20 Our Stolen Generations were taken from their families.

‘The Stolen Generations represented an example of the many and continued attempts to assimilate people and breed Aboriginality out of people, after the era of frontier killing was over.’ (Melbourne)

But First Nations also re-gathered themselves. We remember the early heroes of our movement such as William Cooper, Fred Maynard, Margaret Tucker, Pearl Gibbs, Jack Patten and Doug Nicholls, who organised to deal with new realities.

The Annual Day of Mourning was declared on 26 January 1938. It reflected on the pain and injustice of colonisation, and the necessity of continued resistance in defence of First Nations. There is much to mourn: the loss of land, the loss of culture and language, the loss of leaders who led our struggle in generations past.

‘Delegates spoke of the spiritual and cultural things that have been stolen. Delegates spoke of the destruction of boundaries because of the forced movement of people, the loss of First Peoples and Sovereign First Nations spirituality, and the destruction of language.’ (Dubbo)

‘The burning of Mapoon in 1963 was remembered: “Mapoon people have remained strong, we are still living at Mapoon. Mapoon still exists in western Cape York but a lot of our grandfathers have died at New Mapoon. That isn’t where their spirits need to be. “’ (Cairns)

But as we mourn, we can also celebrate those who have gone before us. 25 In a hostile Australia, with discrimination and persecution, out of their mourning they started a movement – the modern movement for rights, equality and self-determination.

‘We have learnt through the leaders of the Pilbara Strike, we have learnt from the stories of our big sisters, our mothers, how to be proud of who we are.’ (Perth)

‘The old men and women were carrying fire. … Let’s get that fire up and running again.’ (Darwin)

Activism

The movement for political change continued to grow through the 20th Century. Confronted by discrimination and the oppressive actions of government, First Nations showed tenacity, courage and perseverance.

‘Those who came before us marched and died for us and now it’s time to achieve what we’ve been fighting for since invasion: self-determination.’ (Adelaide)

‘Torres Strait Islanders have a long history of self-government. The civic local government was established in the late 1800s, and in the 1930s after the maritime strikes, local councils were created, and in the 1990s, the TSRA. The Torres Strait Islander peoples also have rights under the Torres Strait Treaty.’ (Torres Strait)

Our leaders knew that empowerment and positive change would only come from activism.

Right across Australia, First Nations took their fight to the government, the people and the international community. From Yorta Yorta country, Yirrkala and many other places, people sent petitions urging the King, the Prime Minister and the Australian Parliament to heed their calls for justice. There were strikes for autonomy, equality and land in the Torres Strait, the Pilbara and Palm Island.

‘The history of petitions reminded people about the nationally significant Palm Island Strike. So many people from this region had been removed from Country to the “penal settlement” of Palm Island since its establishment in 1916. The Strike was also sparked by a petition, this time from seven Aboriginal men demanding improved wages, health, housing and working conditions, being ignored by the superintendent. We commemorate 60 years of the Strike in June 2017.’ (Cairns)

Our people fought for and won the 1967 Referendum, the most successful Yes vote in Australian history. In front of the world, we set up an embassy on the lawns of Parliament House and we marched in the streets of Brisbane during the Commonwealth Games.

In the west, grassroots leaders like the late Rob Riley took the fight on sacred sites, deaths in custody and justice for the Stolen Generations to the highest levels of government. Land Rights At the heart of our activism has been the long struggle for land rights and recognition of native title. This struggle goes back to the beginning. The taking of our land without consent represents our fundamental grievance against the British Crown.

The struggle for land rights has united First Nations across the country, for example Tent Embassy activists down south supported Traditional Owners in the Territory, who fought for decades to retain control over their country.

The Yolngu people’s fight against mining leases at Yirrkala and the Gurindji walk-off from Wave Hill station were at the centre of that battle. Their activism led to the Commonwealth legislating for land rights in the Northern Territory.

The epic struggle of Eddie Mabo and the Meriam people resulted in an historic victory in 1992, when the High Court finally rejected the legal fallacy of terra nullius and recognised that the land rights of First Nations peoples survived the arrival of the British.

Makarrata

The invasion of our land was met by resistance.

But colonisation and dispossession cut deeply into our societies, and we have mourned the ancestors who died in the resistance, and the loss of land, language and culture. Through the activism of our leaders we have achieved some hard-won gains and recovered control over some of our lands. After the Mabo case, the Australian legal system can no longer hide behind the legal fiction of terra nullius.

But there is Unfinished Business to resolve. And the way to address these differences is through agreement making.

‘Treaty was seen as the best form of establishing an honest relationship with government.’ (Dubbo)

Makarrata is another word for Treaty or agreement-making. It is the culmination of our agenda. It captures our aspirations for a fair and honest relationship with government and a better future for our children based on justice and self-determination.

‘If the community can’t self-determine and make decisions for our own community regarding economic and social development, then we can’t be confident about the future for our children.’ (Wreck Bay)

Through negotiated settlement, First Nations can build their cultural strength, reclaim control and make practical changes over the things that matter in their daily life.

By making agreements at the highest level, the negotiation process with the Australian government allows First Nations to express our sovereignty – the sovereignty that we know comes from The Law.

‘The group felt strongly that the Constitution needed to recognise the traditional way of life for Aboriginal people. … It would have to acknowledge the “Tjukurrpa” – “our own Constitution”, which is what connects Aboriginal people to their creation and gives them authority.’ (Ross River)

‘There is a potential for two sovereignties to co-exist in which both western and Indigenous values and identities are protected and given voice in policies and laws.’ (Broome)

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

The following guiding principles have been distilled from the Dialogues. These principles have historically underpinned declarations and calls for reform by First Nations.

They are reflected, for example, in the Bark Petitions of 1963, the Barunga Statement of 1988, the Eva Valley Statement of 1993, the report on the Social Justice Package by ATSIC in 1995 and the Kirribilli Statement of 2015.

They are supported by international standards pertaining to Indigenous peoples’ rights and international human rights law.

These principles governed our assessment of reform proposals:

1. Does not diminish Aboriginal sovereignty and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty.

2. Involves substantive, structural reform.

3. Advances self-determination and the standards established under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

4. Recognises the status and rights of First Nations.

5. Tells the truth of history.

6. Does not foreclose on future advancement.

7. Does not waste the opportunity of reform.

8. Provides a mechanism for First Nations agreement-making.

9. Has the support of First Nations.

10. Does not interfere with positive legal arrangements.

1. Does not diminish Aboriginal sovereignty and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty

Delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues stated that they did not want constitutional recognition or constitutional reform to derogate from Aboriginal sovereignty and Torres Strait Islander sovereignty. All of the Dialogues agreed that they did not want any reform to have consequences for Aboriginal sovereignty; they did not want to cede sovereignty: Melbourne, Hobart, Broome, Dubbo, Darwin, Perth, Sydney, Cairns, Ross River, Brisbane, Torres Strait and Canberra.

The Barunga Statement called ‘on the Commonwealth Parliament to negotiate with us a Treaty or Compact recognising our prior ownership, continued occupation and sovereignty and affirming our human rights and freedoms.’

The Expert Panel’s report in 2012 stated that the legal status of sovereignty is as follows:

‘Phillip’s instructions assumed that Australia was terra nullius, or belonged to no-one. The subsequent occupation of the country and land law in the new colony proceeded on the fiction of terra nullius. It follows that ultimately the basis of settlement in Australia is and always has been the exertion of force by and on behalf of the British Crown. No-one asked permission to settle. No-one consented, no-one ceded. Sovereignty was not passed from the Aboriginal peoples by any actions of legal significance voluntarily taken by or on behalf of them.’

And the final report of the Joint Select Parliamentary Committee found that ‘at almost every consultation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander participants raised issues of sovereignty, contending that sovereignty was never ceded, relinquished or validly extinguished. Participants at some consultations were concerned that recognition would have implications for sovereignty’.

2. Involves substantive, structural reform

Delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues stated that the reform must be substantive, meaning that minimal reform or symbolic reform is not enough.

Dialogues emphasising that reform needed to be substantive and structural include: Hobart, Broome, Darwin, Perth, Sydney, Ross River, Adelaide, Brisbane, Torres Strait and Canberra.

This is consistent with the Kirribilli Statement that ‘any reform must involve substantive changes to the Australian Constitution. A minimalist approach, that provides preambular recognition, removes section 25 and moderates the races power [section 51 (xxvi)], does not go far enough and would not be acceptable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples’.

This is consistent with Article 3 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples: ‘Indigenous peoples have the right of self-determination.

By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development’.

In addition, the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples provides that ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to the recognition, observance and enforcement of Treaties, Agreements and Other Constructive Arrangements concluded with States or their successors and to have States honour and respect such Treaties, Agreements and other Constructive Arrangements’.

3. Advances self-determination and the standards established under the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

Many delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues referred to the importance of the right to self-determination as enshrined in Article 3 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

In 1988, the Barunga Statement called for the recognition of our rights ‘to self-determination and self-management, including the freedom to pursue our own economic, social, religious and cultural development.’ One of the fundamental principles underpinning ATSIC’s report on the Social Justice Package was ‘self-determination to decide within the broad context of Australian society the priorities and the directions of their own lives, and to freely determine their own affairs.’

Dialogues that referred to self-determination and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Peoples include: Hobart, Broome, Darwin, Perth, Sydney, Cairns, Ross River, Adelaide, Brisbane, Torres Strait and Canberra.

4. Recognises the status and rights of First Nations

Many delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues wanted the status and rights of First Nations recognised. Dialogues that referenced status and rights of First Nations include:

Melbourne, Hobart, Broome, Dubbo, Darwin, Perth, Sydney, Cairns, Ross River, Adelaide, Brisbane, Torres Strait 94 and Canberra.

The Barunga Statement called for the government to recognise our rights ‘to respect for, and promotion of our Aboriginal identity, including the cultural, linguistic, religious and historical aspects, and including the right to be educated in our own languages and in our own culture and history.’

One of the fundamental principles underpinning ATSIC’s report on the Social Justice Package was ‘recognition of Indigenous peoples as the original owners of this land, and of the particular rights that are associated with that status.’

Consistent with Article 3 on the right of self-determination, the preamble of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples recognises ‘the urgent need to respect and promote the inherent rights of indigenous peoples which derive from their political, economic and social structures and from their cultures, spiritual traditions, histories and philosophies, especially their rights to their lands, territories and resources’.

5. Tells the truth of history

The Dialogues raised truth-telling as important for the relationship between First Nations and the country. Many delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues recalled significant historical moments including the history of the Frontier Wars and massacres.

Dialogues that stressed the importance of truth-telling include: Melbourne, Broome, Darwin, Perth, Sydney, Cairns, Ross River, Adelaide, Brisbane, Torres Strait.

The importance of truth-telling as a guiding principle draws on previous statements such as the ATSIC report for the Social Justice Package.

The Eva Valley Statement said that a lasting settlement process must recognise and address historical truths. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples enshrines the importance of truth-telling, as does the United Nations General Assembly resolution on the basic principles on the right to a remedy and reparation for victims of gross violations of international human rights law and serious violations of international humanitarian law.

In its Resolution on the Right to the Truth in 2009, the Human Rights Council stressed that the victims of gross violations of human rights should know the truth about those violations to the greatest extent practicable, in particular the identity of the perpetrators, the causes and facts of such violations, and the circumstances under which they occurred.

And that States should provide effective mechanisms to make that truth known, for society as a whole and in particular for relatives of the victims.

In 2010, the UN General Assembly proclaimed the International Day for the Right to the Truth Concerning Gross Human Rights Violations and for the Dignity of Victims.

In 2012, the Human Rights Council appointed a Special Rapporteur on the promotion of truth, justice, reparation and guarantees of non-recurrence.

In 2013, the UN General Assembly passed the Resolution on the right to the truth.

6. Does not foreclose on future advancement

Many delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues stated that they did not want constitutional reform to foreclose on future advancement. Constitutional reform must not prevent the pursuit of other beneficial reforms in the future, whether this be through beneficial changes to legislation, policy, or moving towards statehood (in the Northern Territory) or towards Territory status (in the Torres Strait). Dialogues that referenced this include: Hobart, Sydney, Darwin, Torres Strait and Canberra.

7. Does not waste the opportunity of reform

Many delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues stated that constitutional reform was an opportunity and therefore should not be wasted on minimalist reform: a minimalist approach, that provides preambular recognition, removes section 25 and moderates the races power (section 51 (xxvi)), does not go far enough and would not be acceptable to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

Dialogues emphasising that reform needed to be more than a minimalist position include: Melbourne, Hobart, Broome, Dubbo, Darwin, Perth, Sydney, Cairns, Adelaide, Torres Strait and Canberra.

8. Provides a mechanism for First Nations agreement-making

Many delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues stated that reform must provide a mechanism for First Nations agreement-making.

Dialogues that referenced a mechanism for agreement-making include: Melbourne, Broome, Perth, Cairns, Ross River, Adelaide, Brisbane and Torres Strait.

The obligation of the state to provide agreement-making mechanisms is reflected in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Article 37 proclaims, ‘Indigenous peoples have the right to the recognition, observance and enforcement of Treaties, Agreements and Other Constructive Arrangements concluded with States or their successors and to have States honour and respect such Treaties, Agreements and other Constructive Arrangements’.

9. Has the support of First Nations

A message from across the First Nations Regional Dialogues was that any constitutional reform must have the support of the First Nations right around the country. The Dialogues emphasised that constitutional reform is only legitimate if First Nations are involved in each step of the negotiations, including after the Uluru Convention.

Dialogues emphasising that reform needed the support of First Nations include: Hobart, Broome, Dubbo, Darwin, Perth, Sydney, Melbourne, Canberra, Brisbane, Torres Strait, Adelaide, Ross River and Cairns.

The failure to consult with First Nations has been a persistent cause of earlier activism.

For example, the 1963 Yirrkala Bark Petition was launched by the Yolngu people after the Federal Government excised their land without undertaking consultation or seeking Yolngu consent. They complained that ‘when Welfare Officers and Government officials came to inform them of decisions taken without them and against them, they did not undertake to convey to the Government in Canberra the views and feelings of the Yirrkala aboriginal people.’

The Eva Valley Statement of 1993 demanded that the development of legislation in response to the Mabo decision have ‘the full and free participation and consent of those Peoples concerned.’

The importance of First Nations’ support is recognised by the United Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which states in Article 3, that through the right of self-determination, Indigenous peoples must be able to ‘freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development’.

The Declaration also recognises in Article 19 that, before any new laws or policies affecting Indigenous peoples are adopted, ‘States shall consult and cooperate in good faith with the indigenous peoples concerned through their own representative institutions in order to obtain their free, prior and informed consent’.

10. Does not interfere with positive legal arrangements

Many delegates at the First Nations Regional Dialogues expressed their concerns that any constitutional reform must not have the unintended consequence of interfering with beneficial current arrangements that are already in place in some areas, or with future positive arrangements that may be negotiated.

Dialogues that supported this principle were: Cairns, Torres Strait and Canberra (Wreck Bay).

Voice to Parliament

A constitutionally entrenched Voice to Parliament was a strongly supported option across the Dialogues. It was considered as a way by which the right to self-determination could be achieved.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples need to be involved in the design of any model for the Voice.

There was a concern that the proposed body would have insufficient power if its constitutional function was ‘advisory’ only, and there was support in many Dialogues for it to be given stronger powers so that it could be a mechanism for providing ‘free, prior and informed consent’.

Any Voice to Parliament should be designed so that it could support and promote a treaty-making process.

Any body must have authority from, be representative of, and have legitimacy in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities across Australia. It must represent communities in remote, rural and urban areas, and not be comprised of handpicked leaders.

The body must be structured in a way that respects culture.

Any body must also be supported by a sufficient and guaranteed budget, with access to its own independent secretariat, experts and lawyers.

It was also suggested that the body could represent Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples internationally. A number of Dialogues considered ways that political representation could be achieved other than through the proposed constitutional Voice.

These included through the designation of seats in Parliament for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (although there was some concern that these politicians would be bound by party politics), the creation of a ‘Black Parliament’ that represents communities across Australia.

There was discussion about how these reforms could be connected to a constitutional body. For instance, the body’s representation could be drawn from an Assembly of First Nations, which could be established through a series of treaties among nations.

Treaty

The pursuit of Treaty and treaties was strongly supported across the Dialogues.

Treaty was seen as a pathway to recognition of sovereignty and for achieving future meaningful reform for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

Treaty would be the vehicle to achieve self-determination, autonomy and self-government.

The Dialogues discussed who would be the parties to Treaty, as well as the process, content and enforcement questions that pursuing Treaty raises. In relation to process, these questions included whether a Treaty should be negotiated first as a national framework agreement under which regional and local treaties are made.

In relation to content, the Dialogues discussed that a Treaty could include a proper say in decision-making, the establishment of a truth commission, reparations, a financial settlement (such as seeking a percentage of GDP), the resolution of land, water and resources issues, recognition of authority and customary law, and guarantees of respect for the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples.

In relation to enforcement, the issues raised were about the legal force the Treaty should have, and particularly whether it should be backed by legislation or given constitutional force. There were different views about the priority as between Treaty and constitutional reform.

For some, Treaty should be pursued alongside, but separate from, constitutional reform.

For others, constitutional reform that gives Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people a voice in the political process will be a way to achieve Treaty.

For others, specific constitutional amendment could set out a negotiating framework, and give constitutional status to any concluded treaty.

Truth-telling

The need for the truth to be told as part of the process of reform emerged from many of the Dialogues.

The Dialogues emphasised that the true history of colonisation must be told: the genocides, the massacres, the wars and the ongoing injustices and discrimination.

This truth also needed to include the stories of how First Nations Peoples have contributed to protecting and building this country.

A truth commission could be established as part of any reform, for example, prior to a constitutional reform or as part of a Treaty negotiation.

ROADMAP

First Stage: Uluru

1. The delegates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Peoples gathered at Uluru this week to sign the Uluru Statement from the Heart which seeks constitutional reforms that will enable the establishment of a Voice of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Peoples, as the precursor to the establishment of a Makarrata Commission to supervise agreements with First Peoples at the local level.

2. As part of the Roadmap, the delegates endorse the following process for appointing a Makarrata Roadmap Working Group: a. One female and one male representative from each of the 13 Regions b. Representatives selected on the basis of their ability to contribute to the working group’s functions c. Representatives are signatories to the Uluru Statement from the Heart and committed to its strategic goal

Second Stage: Following Uluru

3. The Makarrata Roadmap Working Group will be assisted by an Expert Group and an appropriately resourced secretariat.

4. The Working Group will convene as soon as practicable following Uluru and meet with the Referendum Council to convey the Uluru Statement from the Heart, prior to the Referendum Council’s report to the Prime Minister and the Leader of the Opposition.

5. The Working Group will establish a program of meetings and shuttle diplomacy with representatives of the government, the opposition and all of the parliamentary parties and independent cross-benchers to advance the development of a Makarrata Roadmap to be settled between representatives of First Peoples and Parliamentary Representatives.

6. The Working Group will negotiate the specific wording of constitutional reforms. This wording will be brought back for endorsement to a national gathering of the Regional Dialogue representatives to be held at Garma on 4-7 August 2017.

Third Stage: Garma

7. The Uluru signatories will gather at Garma in August.

8. The Prime Minister, Leader of the Opposition and the leaders of the parliamentary parties, as well as independent cross-benchers will be invited to Garma to settle the Makarrata Roadmap.

9. The Roadmap will provide for the Parliament to legislate the Voice and any constitutional provisions will buttress the Voice.

Fourth Stage: Following Garma

10. The Working Group will continue to work with representatives of the government, the opposition and the parliamentary parties, including independent cross-benchers, on the details of the Bill establishing the referendum.

Fifth Stage: Establishing the Voice

11. The Commonwealth Parliament should legislate the powers, functions and representation of the Voice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Peoples.

12. The Voice should be established to enable it to perform its functions as a representative institution of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander First Peoples, enabling First Peoples to deal with the Executive Government of the day as well as the Parliament.

13. The Voice should be accommodated on an appropriate site within the parliamentary circle in Canberra.

14. The promulgation of a Bill to establish the Voice should follow this process:

a. A special Joint Parliamentary Committee should be established to report to the Commonwealth Parliament on a Bill, with 2 First Peoples representatives (one male and one female) from each State and Territory appointed by the First Peoples of that jurisdiction, and 2 representatives of each State and Territory (one government and one opposition) appointed by the parliament of each jurisdiction.

b. This Committee should report to the Commonwealth Parliament within 12 months of its appointment, and to each State and Territory parliament.

c. All First Peoples and representative organisations should be engaged in the design of the Voice and contribute to the development of a Bill.

d. Regional Conferences should be convened to give the opportunity for First Peoples to workshop the design of the Voice, and to make representations to the Committee.

15. A Bill establishing the Voice should be presented to the Commonwealth Parliament within the second year following a successful referendum or settlement of the Garma Makarrata Roadmap.

16. The Voice should be established within 12 months of the passage of the enabling Bill.

Sixth Stage: Towards Makarrata

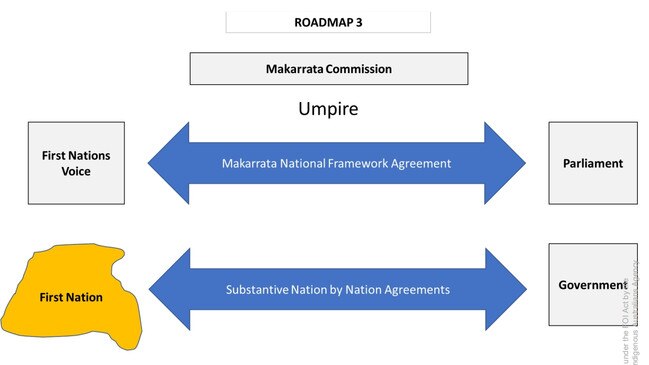

17. Following the report of the special Joint Parliamentary Committee on a Bill establishing the Voice, the Committee should undertake an inquiry into a second Bill establishing an appropriate institution (to be called the Makarrata Commission) to supervise the making of agreements between First Peoples and Australian governments.

18. Engagement and consultation with First Peoples and public hearings should follow the same process as for the promulgation of a Bill establishing the Voice.

19. The Bill establishing the Makarrata Commission should confer all necessary powers and functions to facilitate the settlement of a National Makarrata Framework Agreement between Australian Governments and First Peoples, as well as subsequent First People Agreements at the local level (named in the relevant ancestral language of the First Nation, representing for example the Meriam, Yorta Yorta, Anangu, Wiradjuri and the many First Nations of Australia). The role of the National Native Title Tribunal should be subsumed by the Makarrata Commission, which should have as one of its functions the role of a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to enable all Australians to face the truth of the past and to embrace a common hope for the future.

20. The consultation and negotiation leading up to the settlement of the National Makarrata Framework Agreement should take place between the Voice and the governments of all relevant jurisdictions in a process supervised by the Makarrata Commission.

21. The Makarrata outcome should be legislated by the parliaments of all relevant jurisdictions.