From terrified enemy captives to pink bathtubs: ‘Fab Four’ nurse Colleen Thurgar on Vietnam

One of Australia’s “Fab Four” Vietnam nurses, who faced death in the war zone and hatred at home, is helping to lead an ambitious new mission.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“Go back home.”

It was a grim welcome offered by a Red Cross medic when fresh-faced Colleen Mealy arrived at her dusty military posting south of Saigon in 1967.

But the 23-year-old lieutenant couldn’t have obeyed, even if she had wanted to. As one of the so-called ‘Fab Four’ first Australian female army nurses sent to the Vietnam War, she was there to do a challenging job, starting immediately.

“We didn’t realise what we were heading into – or what we would be coming back to,” she recalls, referencing the public hostility faced by returning Vietnam veterans amid protests against Australia’s commitment to the war.

Five decades on, long after the combat ended and the vitriol faded, the former nurse – now a mother and grandmother, going by her married name of Thurgar – is helping to lead an ambitious new mission: to bring a personal graveside salute to all 523 Australians killed in that terrible conflict.

“Just go and say ‘thank you’ to the boys and let them know they are not forgotten,” says Mrs Thurgar, inviting all Australians to join the Vietnam Veterans Vigil this Thursday, August 3.

Some of those “boys” and many more of their brothers in arms were Mrs Thurgar’s patients and comrades during an extraordinary 12-month posting to the coastal Vung Tau field hospital.

Given just ten days’ notice, the ‘Fab Four” (the nickname bestowed by the media and borrowed from the Beatles at the height of Beatlemania) were flown first-class to Saigon – “I’d never seen so many planes, all military,” remarks Mrs Thurgar – then transferred to Vung Tau and that gallows-humour greeting. Amid primitive families, they set up their quarters and were straight into it.

“When we first started, we didn’t have shifts as such, we just worked. We would stand-to at dusk and dawn because that’s when most of the casualties occurred. If the casualties occurred overnight, they would helicopter them in at first light. So we would work through until everything was done. Then we could have a break.”

The constant pressure kept the medics too busy to dwell on the horrors they witnessed, says Mrs Thurgar, recalling in particular the carnage wrought by “Jumping Jack” mines and small-arms fire. Others presented with illness and accidental injuries.

The stoicism and humour of her Digger patients – a hallmark of the Anzac legend since WW1 – stood out, especially in comparison to their allies.

“When I visited the American hospitals there was a lot of noise, a lot of crying out. When our boys came in, there was no screaming or anything. They were just pleased to be here at the hospital.

“If they came in with a limb off or their leg strapped to their rifle, they’d always say ‘Sister, I hope the family jewels are okay’. And even if their leg was hanging off, they’d just say ‘Oh no, I won’t be dancing again’.”

Sometimes her patients included enemy prisoners, which Mrs Thurgar could find confronting, but “then again, I’m a nurse and that’s what you do – you look after patients”.

Among them were Viet Cong guerrilla women fighters. “They were as good as the men at fighting,” she says; but as captives they were “very frightened”, because once they had been patched up, Australia’s allies in the South Vietnamese army “would come in and take them away and we’d never see or hear of them again”.

She recalls her Fab Four colleague, Lieutenant Terrie Roche, trying to cheer up the terrified women by giving them lipstick. “She used to say, ‘Put some lippy on them, then she’ll feel good’. I’m thinking the poor woman has never seen lipstick in her life.”

The reality is, very few involved in that brutal conflict felt good. Total casualties are almost impossible to estimate, ranging from one million deaths upwards – the majority Vietnamese – with many more wounded, displaced and impoverished and the bloodshed spilling over into surrounding countries. Sixty thousand Australians served and more than 3000 were wounded; many of those returning suffered post-combat trauma; then had to contend with contempt and worse from a public that had welcomed their World War predecessors as heroes.

Mrs Thurgar, originally from SA and now based in Canberra, recalls seeing red paint tipped over one soldier; even the female nurses were flown home at night and told to wear civilian clothing, not uniform, to avoid negative attention.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the end of Australia’s 11-year involvement in Vietnam, with a national commemorative service in Canberra on Vietnam Veterans’ Day, August 18; and a medallion and certificate of recognition for all veterans, all of whom are ageing – many of whom are no longer alive.

The Vietnam Veterans Vigil on August 3 – the brainchild of a small group of veterans including Mrs Thurgar and her former husband John Thurgar – brings a different touch. Aussies are invited to visit a gravesite or memorial at any time for a service of remembrance or to pay respect to the fallen and to show solidarity with their families, with a gesture large or small. Those who take part are encouraged to register their visit beforehand then take a photo and share it.

Among the 523 graves is that of the only Australian servicewoman listed as a fatality, Victorian army nurse Barbara Black, who was diagnosed with leukaemia in Vietnam and is regarded as a trailblazer for successfully lobbying for legal equality in female veterans’ entitlements before she died.

“I haven’t got a tick against her name,” muses Mrs Thurgar. “I hope someone is going to visit Barbara.”

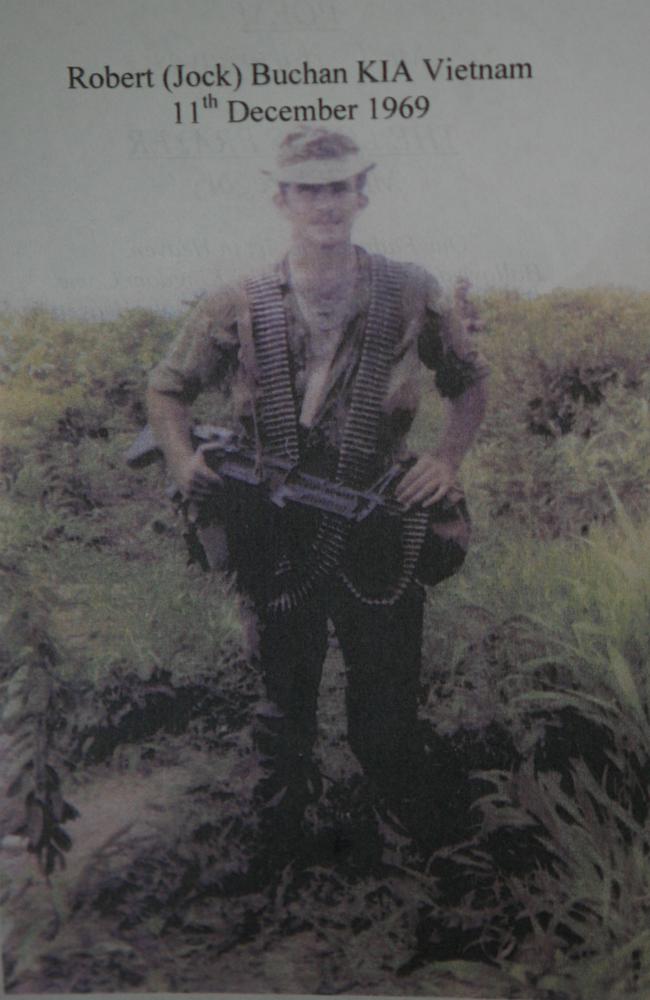

There are also gravesites in Malaysia and as far afield as Birkhill in Scotland, where lance corporal Robert Buchan is laid to rest and where a dusk service will be held.

After leaving the army when she fell pregnant, Mrs Thurgar moved into civilian nursing but maintained her veteran contacts as ACT chair of both the RSL and Legacy.

She continues to visit Vietnam – “I love it there” – and while this is a time of sombre remembrance, she celebrates the bonds she made there and occasional moments of levity.

Asked to share one, she cites the saga of the pink bathtub: how an offhand comment to her father about missing bathing facilities was passed on to their local MP, then went right up to the defence minister and top brass.

“A lot of toing and froing went on,” she laughs. “I got carpeted for it!”

Thinking it was all over, Mrs Thurgar was as stunned as anyone when “out of the blue up turns two pink bathtubs just before I was going home.”

The baths sat in the sand dunes, unconnected until later; but Mrs Thurgar says she went and sat in one anyhow, having a beer, thinking “Gee, Dad you caused me a lot of trouble”.

For a list of gravesites, ideas on how to be part of the vigil and to register, go to www.vvv.org.au

Originally published as From terrified enemy captives to pink bathtubs: ‘Fab Four’ nurse Colleen Thurgar on Vietnam