Robert J. Hawke: The man who changed Australia forever

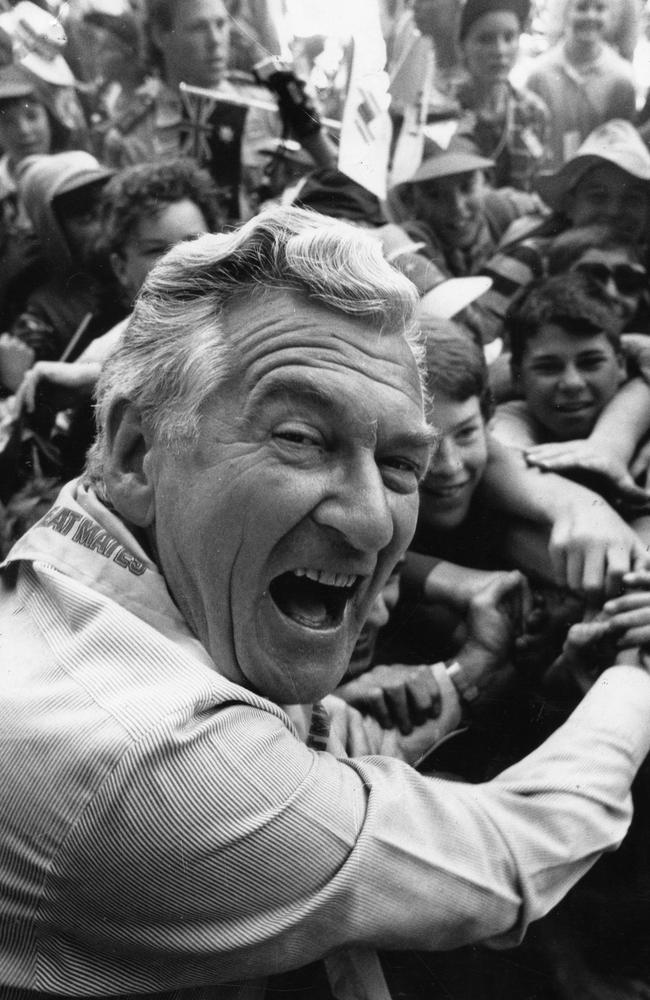

Robert J. Hawke was as Aussie as the next guy. Known as just “Bob” to most Australians, his popularity soared as he used his wit, vigour and genuine love of his country to change the nation forever in an unforgettable way.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When news broke that Bob Hawke had passed silently from this life, a busy nation gripped by the tension of a federal election seemed to stop.

Social media was filled with outpourings: tributes, memories, skolled beers, a poignant letter he penned as prime minister to a little girl who’d lost her grandma.

Australia has lost prime ministers and celebrities before, but few of their absences will be felt as keenly as that of Hawke, whose persona was one part brilliant, one part bad boy, and 100 per cent Australian.

From the humble roots that seem common to so many great leaders, Hawke’s time in office was one where he pointed Australia in the direction we needed to go to step into the future.

In his death, now, his memory is a reminder of how far we have come from a past that seems at once both simpler and more sophisticated.

Bob Hawke was many things to many people but the most endearing public image that cemented his popularity was a boat race.

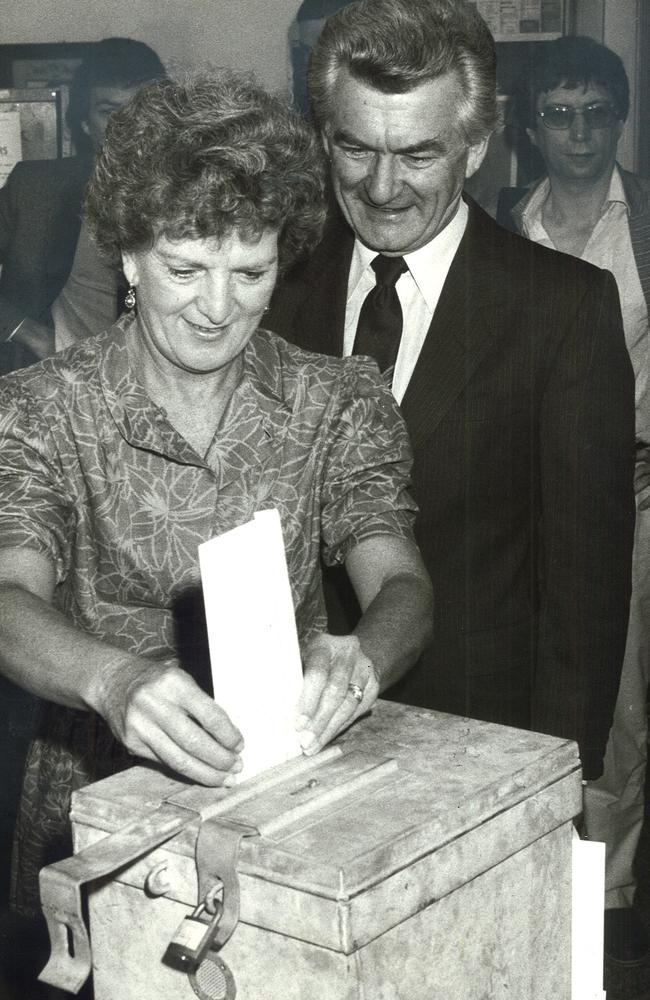

In 1983, Hawke was already widely and highly regarded as a union man who fought for worker rights and a broad social and economic reformer with courage and conviction as prime minister, backed by a hand-picked power-charged Cabinet.

There was also that dubious but legendary honour with the yard glass of beer, the general drinking and womanising.

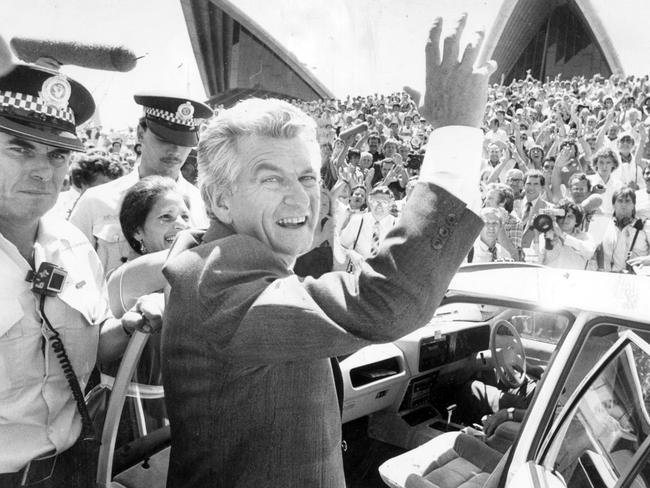

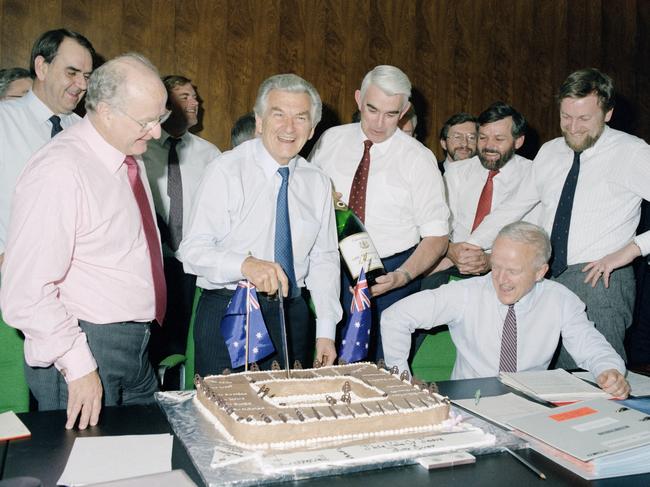

But in the public’s eye Hawke became one of them when Australia II wrested the 132-year America’s Cup trophy from the United States in one of the nation’s greatest ever sporting moments.

The victory, to end America’s year dominance in what was the longest winning sporting streak in history, lifted the national mood in the midst of an economic crisis but more so when their prime minister effectively declared the day a national holiday.

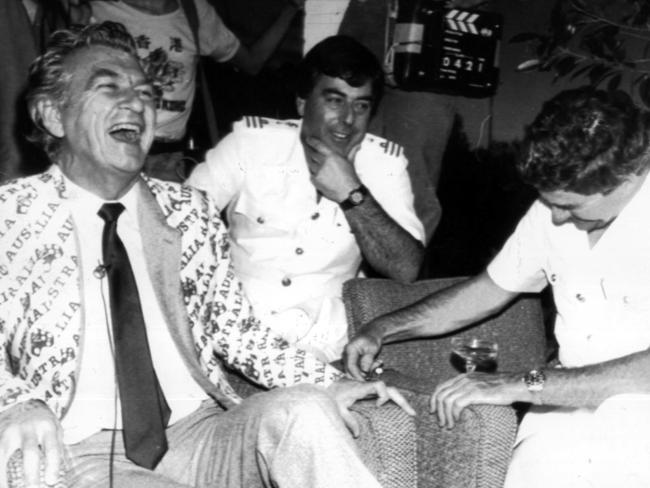

“I’ll tell you what … any boss who sacks anyone for not turning up to work today is a bum!” he said before bursting into a fit of laughter in what has become one of the most replayed filmed moments of the national political archive.

Hawke had earlier decided to take Cabinet meetings out of Canberra and hold them in other states as part of inclusion and national unity and sharing in the political power base that was the ACT.

It was fortuitous, or orchestrated, that in September 1983 the Cabinet meeting was in Perth from where the Australian syndicate’s yacht cup challenge was based.

As the race was held off the US east coast in Newport, Rhode Island, that night in Australia Hawke and his Cabinet stayed up to watch the live broadcast.

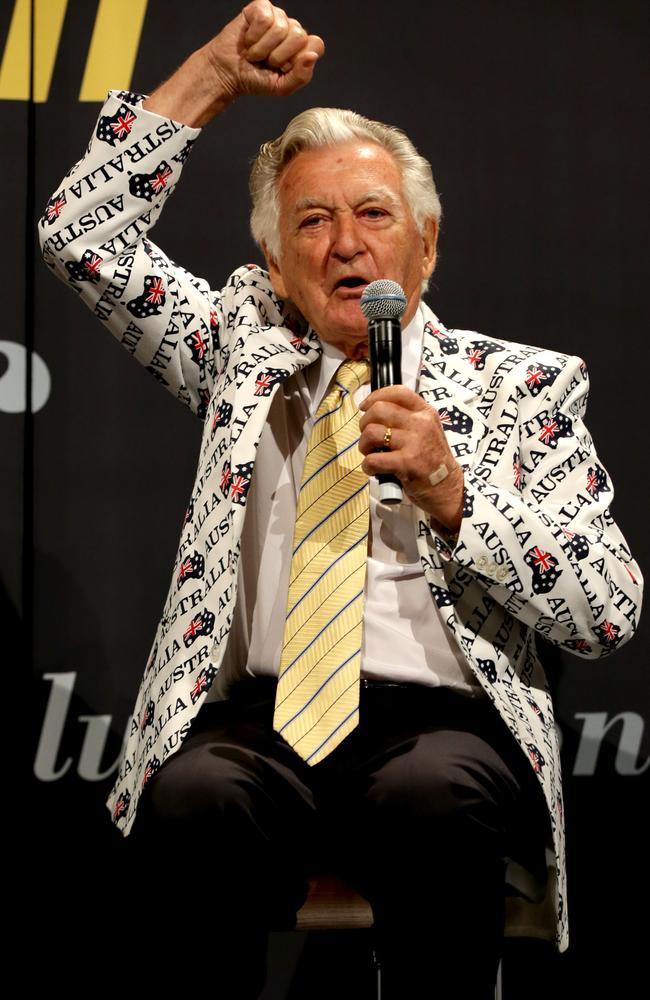

The next day, wearing a white jacket adorned with Australian flags, Hawke strode into the Royal Perth Yacht Club where revellers had watched the winged-keel Australia II’s stunning victory when he dropped his infamous ‘bum’ line.

The Cabinet meeting set for that day was postponed.

Many around the country skipped work and would cite the prime minister as saying it was OK.

Hawke united Australia in that moment and despite his own blue collar union career, the electorate broadly believed he would act in the interest of all.

“I’ve got to say of all the many brilliant things I said as prime minister I think the one that is remembered the most is what I said then, that the employer who sacked a worker for being late that day was a bum,” Hawke would say later.

“I still get regaled repeatedly with that one.”

The beer-drinking, cigar smoking, sports mad, self-confessed larrikin was one of the people who not only shared one of the country’s greatest ever sporting moments but effectively led the celebratory mood.

His uncut and natural response to a sporting triumph was not what the public had seen from their scripted, polished leaders.

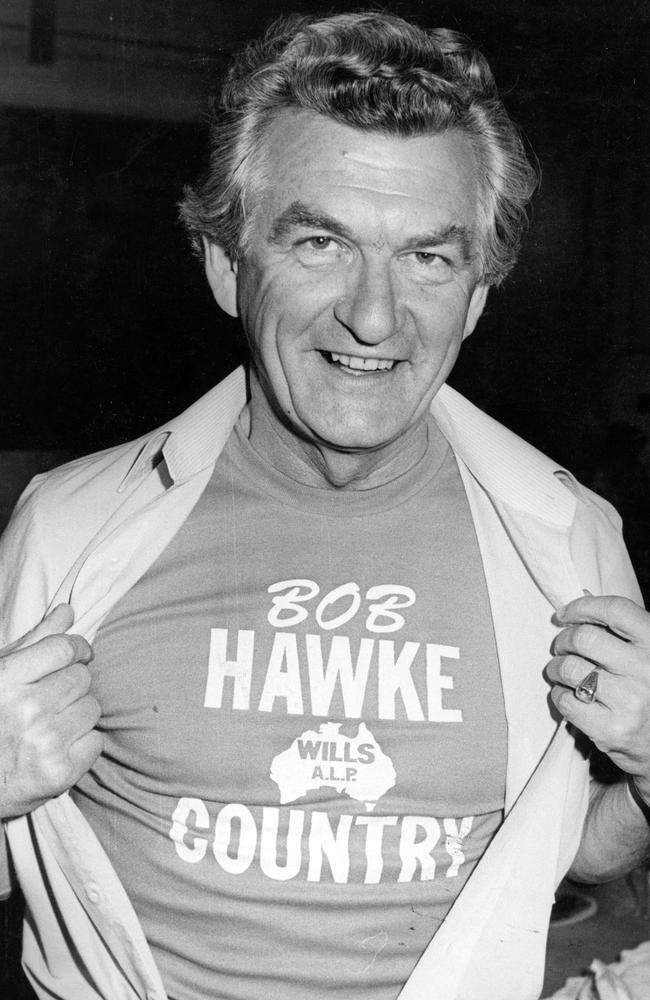

He was as Aussie as the next guy and showing that level of national pride proved it.

If he was genuine in this then perhaps he was genuine also in his policies, an enlivened electorate believed.

It was a defining moment that set Hawke on his way to becoming the longest serving Labor prime minister in history.

But in his eyes there was an earlier event he cites as more of a scene setter.

Hawke was rare in that he had a common touch and approach and was instilled with a strong sense of social justice and self-confidence and courage to tell it how it was.

He was also disarmingly smart.

Hawke graduated from the University of Western Australia with a BA degree and a Bachelor of Laws and was awarded a Rhodes Scholarship to attend University College Oxford in the UK where he undertook a Bachelor in philosophy, politics and economics.

Hawke would later transfer to a Bachelor of Letters study and here wrote a thesis on wage-fixing in Australia, a doctrine that would later guide his reform as leader.

But it was at this time he also entered into a college challenge that he believed endeared him more to the Australia public than anything else.

Hawke set a new Guiness World Record for beer drinking by downing 2.5 imperial pints in a yard glass in 11 seconds.

In his 2011 memoirs he noted that this skolling notoriety endeared him to a people with a strong beer culture.

But his drinking didn’t come without its widely reported challenges.

“Under the very great pressures of the job that I have, I tend, I think occasionally, to take too much refuge in having a drink and I think that has helped me but on occasions I have taken that refuge to much,” Hawke admitted in 1975, before he was Labor leader.

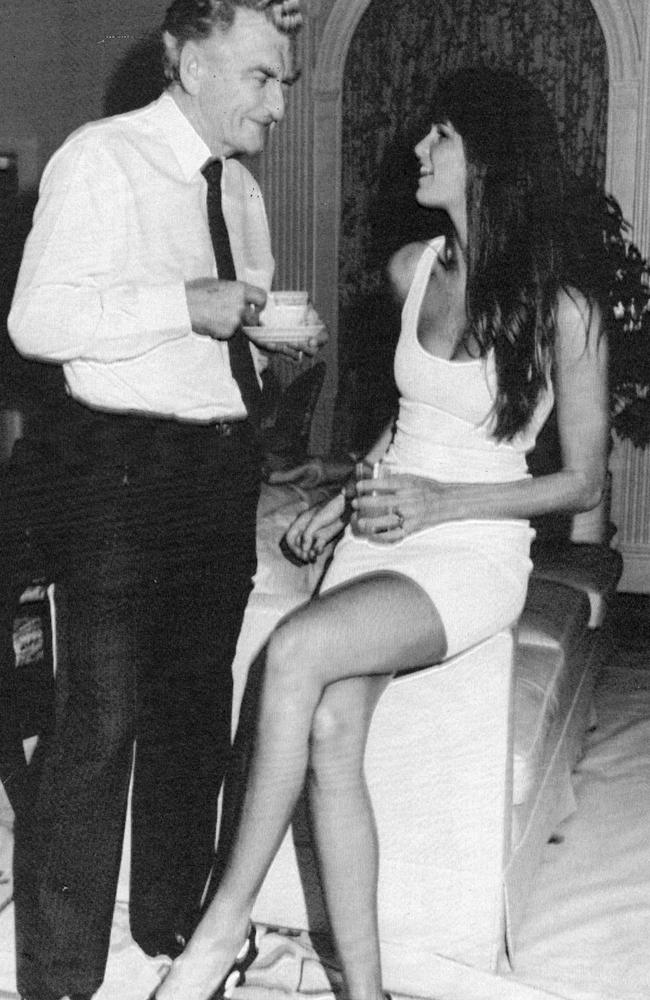

There was another early example of his Aussie-ness and would endear him with the media following an infamous clash with American crooner Frank Sinatra.

Sinatra had flown into Melbourne on July 9, 1974 for a comeback five-show performance.

On arrival a female journalist rushed to interview him, disguised as his former wife, and Sinatra used the scene as part of his onstage monologue bemoaning female journalists as cheap “hookers working for a back and a half”, and others as bums.

The journalists’ union demanded an apology which he scoffed at before then ACTU boss Bob Hawke slapped a ban on ‘Old Blue Eyes’ tour.

Among the black ban were transport workers refusing to refuel his jet.

Hawke said unless he planned to walk on water, Sinatra’s tour would not go ahead.

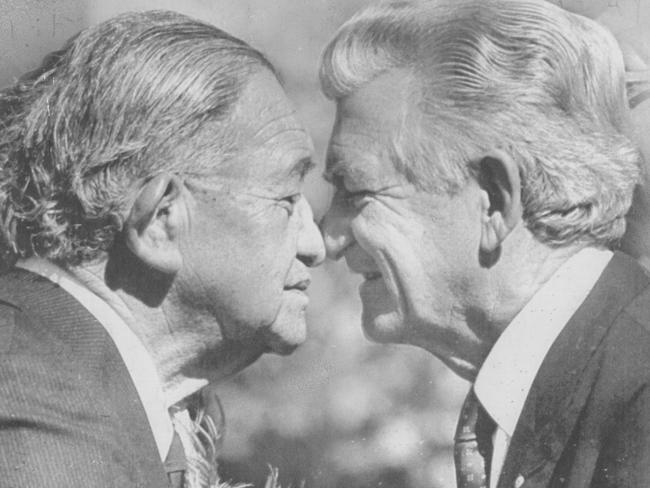

Finally, Hawke met Sinatra, and over four hours of drinks and discussions, Sinatra agreed to say he did not intend any reflection on the moral character of the Australian media.

Hawke was a natural born leader, never one back away from a fight he felt strongly about, but he was also never afraid to let his true feelings play out in public, and that was in part what endeared him to so many Australians.

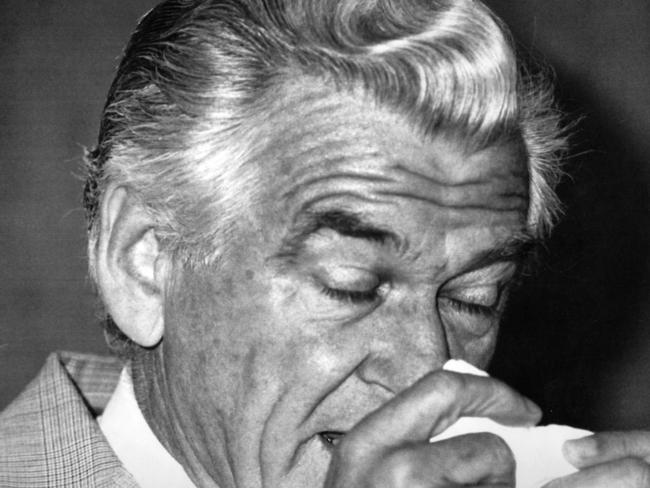

When Hawke famously cried about the ravages of his daughter Rosslyn’s heroin addiction, he was sharing a private pain, but when he also shed public tears at a press conference about China’s brutality in using tanks to mow-down protesters in 1989 at the Tiananmen Square massacre, he showed Australians the true depths of his emotion, not just for his own family but for humanity.

Hawke was instilled at an early age with a sense of destiny, forged by the death of his older brother Neil and his doting schoolteacher mother Ellie, who constantly assured him as a child he was heading for great things.

Hawke himself described a near-death experience from a motorcycle accident at the age of 17 as a catalyst for him wanting to not waste his life and strive to do good.

He would later remark, however, that he appreciated his following and the power he had as a leader.

“The essence of power is the knowledge that what you do is going to have an effect, not just an immediate but perhaps a lifelong effect, on the happiness and wellbeing of millions of people and so I think the essence of power is to be conscious of what it can mean for others,” he once said.

At a function in Sydney on the 30th anniversary of the America’s Cup win Hawke reminded the public what he was all about as he again donned that famous celebratory jacket.

He was very much part of that story of success which guided his own good professional fortunes.

Originally published as Robert J. Hawke: The man who changed Australia forever