Australians call Butterfly Foundation with reports of eating disorders rising

More Australians are reporting eating disorders and body image issues, but some have also revealed how they are finding ways to cope. WARNING: Distressing

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Australians with eating disorders are waiting up to six months for help as demand for services surges during the pandemic.

Isolation, changes to food and exercise routines, and a lack of social connection has placed extra pressure on people battling Bulimia, Anorexia Nervosa and other serious health conditions.

While statistics are not yet available for the impact of the latest restrictions, the Butterfly Foundation has seen an increase in contacts from states experiencing lockdown over the past 18 months.

Last year, contacts to the Butterfly Foundation’s webchat increased by 116 per cent, and during the first school term of 2021 demand for the organisation’s prevention services increased by 150 per cent compared to pre-Covid term 1 in 2019.

Manager of Butterfly’s National Helpline and Recovery Support Services Joyce Tam said lockdowns can exacerbate symptoms, particularly as accessing treatment and support has become more difficult, with both the public and private sectors struggling to meet demand.

“What we’re hearing via the Helpline are a lot more distressing calls from people experiencing all different presentations of eating disorders,” she said.

“Whether it be Anorexia Nervosa, Binge Eating Disorder, Bulimia, or Other Feeding and Eating Disorders (OSFED), every eating disorder presentation is likely to be impacted by the pandemic.”

Data collected by the National Eating Disorders Collaboration (NEDC) from all states and territories shows people living with an eating disorder are waiting four to six months to access assessment and treatment in both the public and private sector.

The NEDC, an initiative of the federal government, said most public and private services are reporting around a 50 per cent increase in referrals as compared to the same time in 2019.

Wait lists for admission to eating disorder inpatient services has increased, resulting in more complex and acute medical and psychiatric presentations on admission to medical beds.

“For private practice, wait lists for mental health and dietetic services are up to six months long, with many practitioners closing their books due to the unrelenting demand and an inability to take on any additional patients,” the NEDC found.

In late 2019, a new suite of Medicare item numbers for eating disorders was introduced to support a model of evidence-based care for eligible patients living with an eating disorder.

In response to the mental health impacts of the pandemic, the Australian Government has introduced a range of telehealth (video and telephone) Medicare items for people to be able to continue to receive care even if unable to attend face-to-face appointments.

There has also been an increase in the number of Medicare subsidised psychological therapy sessions available, with people on a Mental Health Treatment Plan able to access an additional 10 sessions (20 sessions total).

Ms Tam said early intervention is vital in reducing the severity and duration of an eating disorder.

“We encourage anyone who is impacted by eating disorders or body image concerns to reach out and get help as soon as you think something might be wrong.”

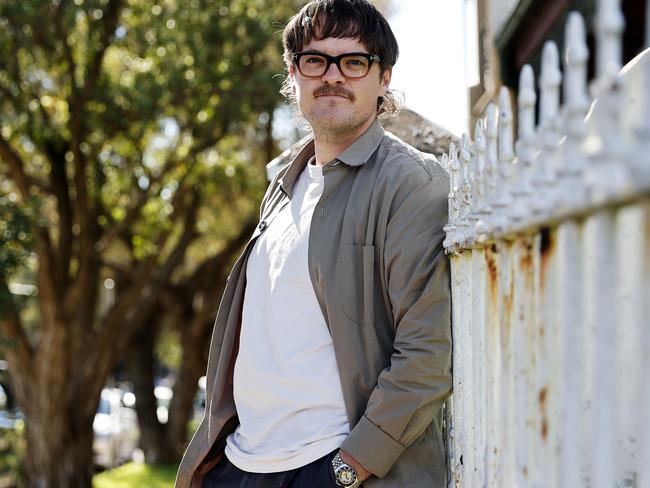

Patrick Boyle was diagnosed with OSFED (Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder) in 2019 after a lifelong preoccupation with his weight.

The 27-year-old freelance writer from Sydney’s inner-west said the lockdown had taken a mixed toll on his health.

“In terms of my body and my mental health, it’s kind of a little up and down,” he said.

“Making sure you are on top of the preoccupation, that is the problem. I’ve see flare ups of that in the last month, particularly because my structure is removed, so I don’t do all the usual things I do to stay sane.

“Also the other hard thing is I’ve worked really hard to make sure I don’t think of fitness in an obsessive way.”

Increased use of social media during lockdown is another area Mr Boyle has had to take steps to control.

The constant bombardment of food, body and fitness images and videos can have a detrimental effect.

“Social media especially I mute, block and report anything that makes me feel like sh-t,” he said.

“It’s kind of a fine line because a lot of people just want to share their love of food, or share their love of fitness or share their love of whatever but they don’t realise how toxic it is for you.

“I’ve realised that no regulatory body or social media company is going to do it for you. If you want to be on social media you just have to manage your own feed and filter out all the sh-t that makes you feel bad.”

And, he points out, there’s always the “mute” button too.

Molli Johns has suffered a restrictive eating disorder for the last five years and in 2019 was diagnosed with atypical Anorexia, OSFED (Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder).

The 18-year-old Melbourne dance student and dance teacher said the multiple Victorian lockdowns had a mixed impact on her mindset and eating habits.

“On the one hand it helped my eating habits to become more ‘normal’ due to the removal of social settings – taking away the social situations where body standards occur and the external stressors that caused me to use food as a coping mechanism,” she said.

“On the other hand there were times where my food and eating habits were more controlled by my eating disorder as the distractions that usually help me were no longer accessible, like spending time with friends, family, having a routine and exercise in gyms.

“Each lockdown has been very different, always depending on my mental state, lockdown and the people I’m surrounded by.”

Social media is a huge part of Ms Johns advocacy for mental health, but she says it can also act as a hindrance.

“There are so many accounts that post content that promotes eating disorders so it really can go both ways,” she said.

“Every eating disorder is so different; personally I had experiences where my eating disorder made me feel as though everything correlated to my weight, including amount of likes, views and follows.”

She finds it helpful to take breaks and consistently re-evaluate which accounts make social media a positive experience.

“It is so important that you fill your feed with the supportive social media accounts so that it makes you feel good about yourself,” she said.

TV has been just a big a problem as social media during lockdown as there is so much content that promotes a certain look.

“Honestly, there’s only one film that I have watched that didn’t have triggering content,” she said.

FAST FACTS

About one million Australians – four per cent of the population – are living with an eating disorder in any given year.

Of people with eating disorders, three per cent have anorexia nervosa compared to 12 per cent with bulimia nervosa, 47 per cent with binge eating disorder and 38 per cent with other eating disorders.

While eating disorders are more prevalent in cisgender women, they also occur in all gender identities.

Anyone needing support with eating disorders or body image issues is encouraged to contact: Butterfly National Helpline on 1800 33 4673 (1800 ED HOPE) or email support@butterfly.org.au