Aussie who cheated paralysis eyes off world record on Everest

WHEN Steve Plain was told he might not walk again, he set himself a monumental recovery goal: to reach the top of Mount Everest.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THREE-AND-A-HALF years ago, Steve Plain was told he might never walk again.

Now, he’s sitting at the foot of Mount Everest, eyeing off a world record on the roof of the world.

Right now, it seems only the weather will prevent the 36-year-old from achieving his dream of being the fastest man to conquer the highest mountains on each of the world’s seven continents in less than four months.

If he can reach the summit of Everest by May 22, the Seven Summits speed record will be his.

It’s a far cry from December 2014, when doctors told him the busted neck he’d sustained in the surf might see him confined to a wheelchair.

Plain’s recovery goals weren’t modest hurdles. They were, literally, mountains.

Fast-forward to 2018, and Plain is hard on the heels of the world record set last year by Polish climber Janusz Kochanski, who took 132 days to conquer the seven summits.

Since January, Plain has climbed Mt Vinson (Antarctica), Aconcagua (South America), Kilimanjaro (Africa), Carstensz Pyramid in Papua New Guinea (Australasia) and Australia’s Mt Kosciuszko. He flew to Russia this week to take on Mt Elbrus, the highest peak in Europe, then tackled Denali in Alaska (North America’s tallest).

The biggest hurdle is 8848m Mount Everest, or Sagamartha (goddess of the sky) as the Nepalese call it.

He was hoping to climb on May 10, but weather has conspired to make that impossible.

So he waits. Until Sagamartha’s mood improves.

“I just want to get up, get down, and get home,” he said from Base Camp on May 5.

THE IMPETUS

It’s called a hangman’s fracture.

That’s the spinal injury that cut down Plain in his prime in December, 2014, when a surfing accident at Western Australia’s popular Cottesloe Beach left him paralysed with a busted neck.

One minute he was having his regular morning swim. The next he’d been dumped by a wave, pummelled headfirst into the sand and left facedown in the water, body numb, and unable to breathe.

He came to in the water, and tried to figure out how he’d get his next breath. Two lifesavers spotted his unmoving frame, and dragged him out.

Lying in hospital with unstable breaks to the C2, C3 and C7 vertebrae, a ruptured disc, a contorted spinal cord, and a dissected artery — he realised this was “more than a bit of bruising”.

The hangman’s fracture — so called because its injuries are similar to those sustained in hangings — meant Plain was confined to a hospital bed.

“Lying in that hospital staring at the ceiling with the thought that I may not be able to walk again and do some of the things I wanted to do, I decided right there to give myself some focus in the rehab process,” he told The West Australian last year.

He pushed down the self-pity, anger and fear and flat-out refused to accept the doctors’ prognosis.

They fitted him with a halo brace and months of rehab began.

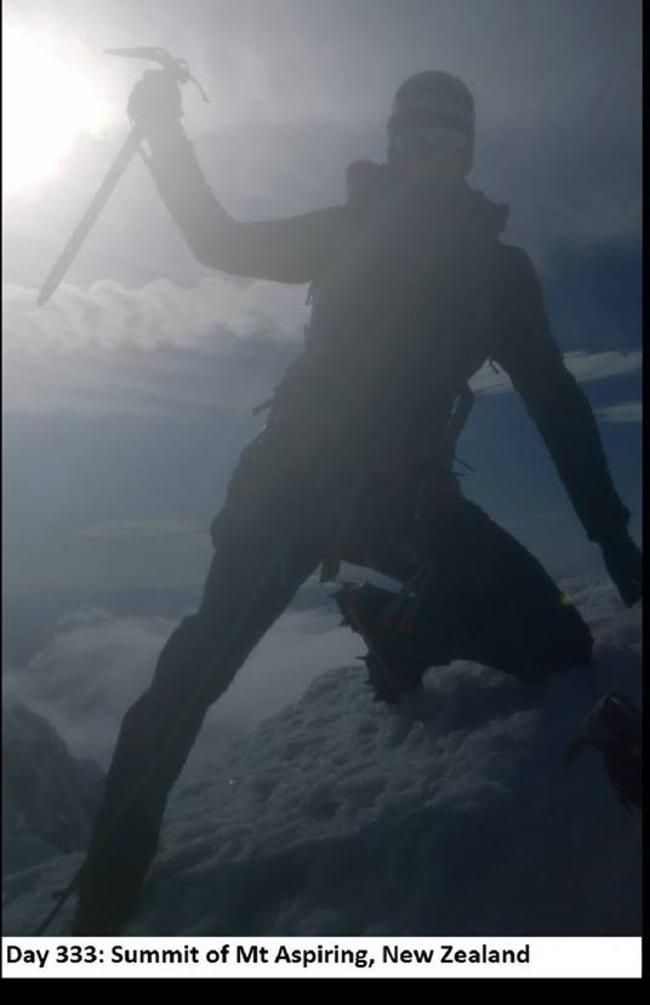

A montage of pictures on his Facebook page tells the story.

Day 1: Lying helpless and scared in hospital, in a neck brace and hospital gown, and on oxygen after being pulled from the surf.

Day 5: Prone in Royal Perth Hospital’s spinal trauma unit, halo brace fitted.

Day 105: Upright, brace still on, but he’s made the outpatients’ clinic.

Day 333: On the summit of Mount Aspiring in New Zealand, ice axe triumphantly aloft.

UP ON EVEREST

Project 7in4 is Plain’s attempt, after his close shave with paralysis, to help those not as lucky by supporting SpinalCure Australia and Surf Life Saving WA.

He is eager to scale Everest, despite the heavy death toll the world’s tallest peak takes on climbers.

Everest has been an obsession since a trip to base camp when he was just 16.

He did a practise climb last year on Lhotse, just 330m lower, which shares the same route as far as camp four.

He’s keeping followers regularly updated via a live tracking blog.

He shares the delights of living at base camp — makeshift showers that “would rank up there with one of the worst I’ve had but feel so good under the circumstances”; and “relative luxuries” not found up higher such as fried eggs and tea.

And spam. Not the internet kind. The canned luncheon meat kind.

He’d never touch the stuff at home, he says, but fried, with a side of potatoes, it’s positively gourmet at altitude.

He’s been making acclimatising trips up and down Everest to its several base camps for weeks.

Now he just wants to finish the job.

Sagamartha isn’t co-operating.

Plain is among 346 mountaineers given permission to scale Everest this spring climbing season.

That number becomes a traffic jam when the sherpas, or Nepali guides who aid their climb and set ropes to the summit, are added to the mix.

It’s another bumper year, despite continuing concerns over the past decade about overcrowding on the world’s highest mountain.

Another 180 climbers are preparing to summit Everest from its north side in Tibet, according to the China Tibet Mountaineering Association.

Each year across about three weeks in May, the mountain offers a narrow window of the right weather to summit.

Get it wrong, and the mountain exacts her toll in lives .

Plain was reminded of that at the start of the month, when he and fellow climbers abandoned a climb to the nearby peak of Nupste just 200m from the summit.

It was late, the avalanches were threatening, and all were exhausted. They reluctantly, but wisely, turned back.

“We had the descent to focus on,” he wrote.

The challenge of Everest, all mountaineers know, isn’t getting up. It’s getting back down safely.

READY TO GO

Plain was desperately hoping for an early May summit, but the weather isn’t playing ball.

“Every day I sit and wait now is another day I lose,” he wrote from Base Camp on May 5.

“Early May has now come and gone and with it the days on my 7 Summits clock keep ticking by. These continuing delays are killing me. And unfortunately based on the current forecast we may still be waiting for some time yet.

“There are strong winds up high at least through to the 10th so no summit window in that time.

Life at high altitude quickly takes its toll on the body, and Plain has to continually refocus his motivations and mind.

Despite an irritating sore throat and cough, he’s acclimatised, “relatively” fit and ready to go. So far, the mountain isn’t.

On May 5, he admitted he felt “pretty sh*t” and hadn’t done much that day.

“Problem is it becomes circular. You feel like sh*t so you rest. You rest too much, you feel like sh*t,” he wrote.

The following day, he’d decided to “stop moping around base camp feeling sorry for myself”, and headed upwards for another acclimatising climb.

Then back to base camp to play cards, eat, sleep, check the news from home on intermittent and expensive wi-fi, and wait.

“The weather forecast still has no good news, so it is just a case of sit and wait,” he said.

“For now I stay squarely focused on getting up and down this mountain. I just hope the weather starts playing ball so that we get a shot at it sooner rather than later.”

Originally published as Aussie who cheated paralysis eyes off world record on Everest