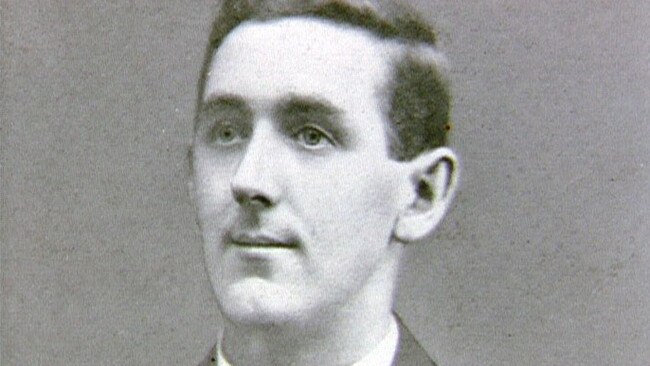

Anzac Day letters from WWI unveil more of Gallipoli hero John Simpson’s life

Aussie schoolchildren have learnt about Simpson and his donkey for decades. Now newly transcribed letters have revealed what Anzac hero John Simpson was really like.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

He was an Englishman, but the Anzac hero John Simpson traversed the Wide Brown Land more than most Aussies, and his sense of humour was as cheeky as any larrikin born under the Southern Cross.

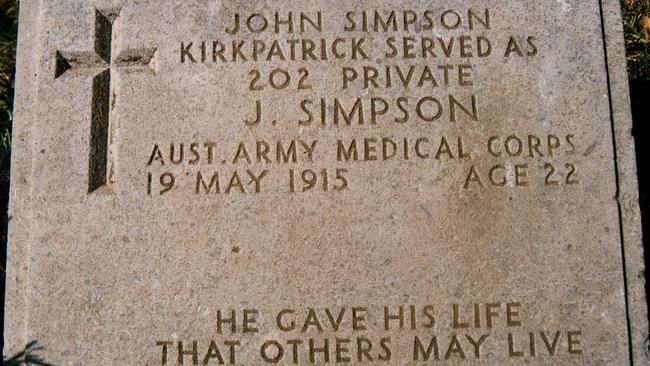

Remembered for bringing the Gallipoli wounded to safety on his donkeys, before his own death on 19 May, 1915, aged 22, John Simpson was a man who “knew no fear,” according to the then Colonel John Monash.

For many decades, Australians have learnt about “Simpson and his donkey” as an Anzac hero, but thanks to an ongoing Australian War Memorial (AWM) project, a fuller picture is emerging, revealing a young man who lived a hardscrabble life, but who never once lost his sense of humour, nor his love for his family.

The AWM is currently transcribing the many letters Simpson sent home to his mother and sister, making them readable and searchable like never before.

The collection is “an invaluable observation of Australia during the outbreak of the First World War from a British person who was travelling the country doing manual work,” an AWM spokesperson said.

Working as a miner, a canecutter and on board merchant ships between 1909-1914, Simpson wrote to his family from Cairns, the Hunter, Melbourne, Port Pirie, Port Kembla, Albany, Bunbury, Fremantle and Geraldton, “Sidney” [sic] and “Adilade” [sic].

He also sent money back home, except at times when he was flat broke.

The letters track Simpson’s fortunes as he traversed the country, insisting to his mother that “carrying his swag” is “just about the best life that a fellow [could] wish for”.

Through sickness and health, he recorded a litany of hard jobs, including one north of Wollongong that “only lasted four shifts and then a gang of us were layed off for slackness”.

“I was on stonework and damned heavey [sic] work it was,” he wrote.

But his cheeky sense of humour never flagged. Having received a photo of his mother in the post he replied: “Mother I think you might have tried to look a bit pleasanter, you look as if you had lost a tanner [sixpence] and found a threepenny dodger.”

In another letter he recounts a Christmas dinner with shipmates which ended in a drunken brawl.

“We drank each other’s health quite a number of times until each man thought he was Jack Johnson,” he wrote, name checking the American world champion boxer of the day.

For Australian military historian Dr Mark Johnston, who wrote the book Stretcher-Bearers: Saving Australians from Gallipoli to Kokoda, Simpson’s letters “show him as a guy who was quite sensitive; he clearly cared about his mother and his sister”.

“He was keen to be part of the war. He felt lucky that he’d been part of the first contingent to go overseas,” he said.

He remains a compelling figure for Australians for a variety of reasons, including his courage and his compassion, Dr Johnston said.

But his initiative also marked him out as a unique character.

“Australian soldiers usually had to stay with their units, and move only when they were told to do something. But here was a guy who actually went off on his own, on the first day after the landing, and got hold of a donkey. He did his own thing,” he said.