‘Media Legends: Journalists who helped shaped Australia’ reveals how giants in the game got their start

THEY’RE some of the biggest names in Australian media. But where did the likes of Mike Sheahan and Terry McCrann get their start? A new book has some surprising answers.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY’RE some of the biggest names in Australian media.

But where did the likes of Mike Sheahan and Terry McCrann get their start?

As thirty-one journalists were last night inducted into the Media Hall of Fame, a new book, Media Legends: Journalists Who Helped Shape Australia, profiles some of the most influential figures in Australian journalism:

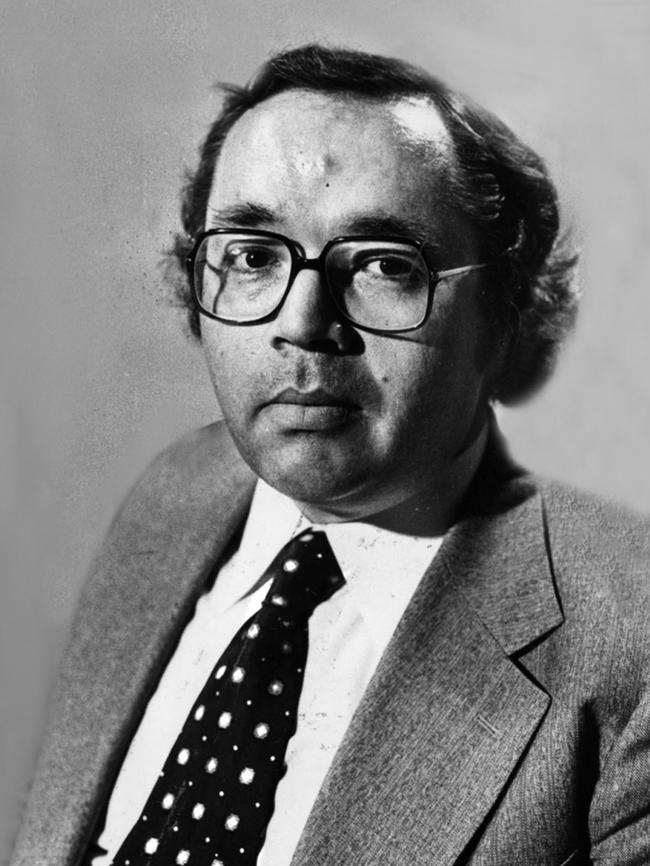

Mike Sheahan

Just as the game has grown from its beginnings as winter exercise for cricketers and pick-up matches in paddocks to the biggest game in the nation, Sheahan transformed himself from an innocent cub reporter on the Werribee Banner — fresh out of Werribee High School in 1964 after three years at Christian Brothers College, North Melbourne — to become the most successful and influential Australian football journalist.

He pursued his twin interests in journalism and football from his earliest days in Werribee, the short-lived Newsday and then at the Hobart Mercury.

In his early days Mike was juggling the demands of general reporting shifts, extra shifts to gain football experience at weekends, plus training and playing for the Werribee Tigers in the VFA and North Hobart Demons in the TFL, where then coach John Devine, who later coached Geelong, described the left-footer as one of the most courageous players he coached.

Reluctantly accepting he perhaps didn’t have the speed or size to make it at the highest level, Mike put his focus into covering the game he had loved since he was a boy.

He returned from Tasmania to join Inside Football in Melbourne, then The Age from 1974 before moving to The Herald in 1979 to succeed Alf Brown as the paper’s chief football writer.

After six years he changed pockets and became the AFL’s media director in 1985, before returning to his natural game as chief football writer for the launch of The Sunday Age in 1989. He was then seduced by the Herald Sun in 1993, where he remained #1 football writer until he “retired” from full-time work at the paper in 2011.

However his platform and influence remained strong: his innovative annual Top 50 player rankings continued in the Herald Sun, he remained a pivotal part of the Fox Footy network, which he has been part of since its inception, principally with the On The Couch television program, and also host of his own concept of an Andrew Denton-type format for football, Open Mike, which grew in popularity and led to his second well-regarded book, the first being Lethal, a biography of Leigh Matthews published in 1986.

Amid all the egos, opinions, competition and complexities of modern football, Sheahan has remained true to himself: someone with a boyish love of the game and all its participants, the work ethic to do the homework, the courage to ask the awkward question and give his sometimes controversial views, and a capacity to tell a story as he sees it without fear nor favour.

This ability to gain and keep the respect of the game’s players, coaches and clubs, despite the inevitable occasional error or lapse in judgment, ensured that for the most pivotal decades of the game’s development he was the likely person to break the news, get the interview, reveal the inside workings, and have the most meaningful analysis and comment.

His spectacles, grey hair and friendly Irish-Catholic nature and manner made him easy fodder for comics and rivals: he was somewhat slow to accept his rising profile, and all that comes with being a recognised leader of the pack, but it was because that’s what he was.

This was underscored by the number of young journalists who would begin their own careers with an ambition “to be the next Mike Sheahan”.

— extract of chapter by Steve Harris, Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of The Age 1997-2001, Editor-in-Chief the Herald Sun 1992-1997, Founding Editor of The Sunday Age 1989-1992.

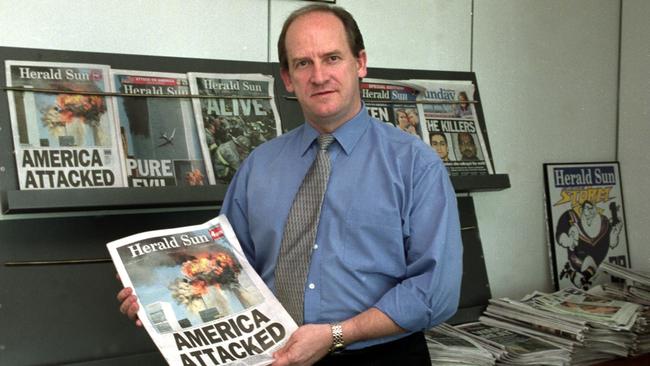

Peter Blunden

Peter Blunden’s bare knuckle approach has not always endeared him to his colleagues or his competitors.

“I’ve never minded polarising people,” Blunden says. “You can’t do a job like running the Herald Sun and be everyone’s best friend — and that’s not what it’s about.

“I reckon I’ve got a lot more friends than enemies, but I don’t mind being loathed by my competitors. That’s a badge of honour to me.”

A quintessential, sleeves-up editor of the classic News Ltd mould, Blunden got the taste for newspapers and journalists from his policeman father, whose retirement job involved monitoring police radios and working his contacts to gather information for the police reporters at the Daily Mirror in Sydney.

Blunden did his cadetship on the stablemate Sunday Telegraph, where he covered everything from television to state politics and industrial relations.

In 1980 he switched to The Australian and worked there for the next 10 years, including terms as Adelaide correspondent, Canberra bureau reporter, chief of staff and assistant editor.

In 1988 he became founding editor of The Australian’s new colour magazine.

“It was hair raising stuff. We started with a phone on the wall and a very small budget, and the first edition was 172 pages,” he recalls. “It’s just a delight to see the magazine still alive and well all these years later.”

Two years later, after editing the first 100 editions of the magazine, Blunden was asked to become editor of the Adelaide Advertiser and left Sydney for the fourth time in his career.

“I had a baptism of fire. In the first couple of months I was there the State Bank collapsed, the Gulf War broke out and the Adelaide Crows were formed. I can tell you which one sold the most papers … the Crows. That was a huge story,” he recalls.

Six years later, after The Advertiser’s transition to become the first Australian daily to introduce colour and the demise of the paper’s competitor, the Adelaide News, he was appointed editor of the biggest selling daily in the country, the Herald Sun.

“I’d always had an affinity with Melbourne and was familiar with what happened here. I came to Grand Finals and Spring Carnivals. I felt very much at home when I got here,” he says.

Blunden’s passion for sport, including racing, all forms of football, tennis and the GP, helped make him feel at home.

“Sport’s a huge part of what I love, and I don’t think there’s a city pound for pound in the world that embraces sport like Melbourne does,” he says.

He says the Herald Sun touches every part of the community, and is proud the paper has more than 90 formal partnerships with community leaders, events and organisations in every element of the city’s life — including sport.

He believes the paper’s power and influence bring with it a responsibility to make the city a better place, and says the heritage and history of events like the Royal Children’s Hospital Good Friday Appeal, the Herald Sun Tour and the Herald Sun Aria are all part of the paper’s DNA.

“Being in touch with the Melbourne community, being part of it and being pro-Victoria, is something we’ve always embraced and it’s what our readers want.

But we don’t go soft. We’ve done a lot of stories that have got up the noses of people who might have been perceived as people we supported. That’s all part of journalism,” Blunden says.

— extract of chapter by Geoff Wilkinson, who retired from the Herald and Weekly Times in 2012. In 2010 he was awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Melbourne Press Club.

Andrew Rule

He’s a handy type of bloke, this Andy Rule. He can sharpen a chainsaw, get rid of your rabbits, grow the best basket of herbs short of some silly TV cooking show, sell fresh eggs from the back of the office car, and pick a fellow scallywag at 100 metres.

He can turn a dollar, craft a scheme, and work more jobs at once than any sane man should manage.

He has a face that would be at home in a shearing shed under a sweat-stained hat, but it’s the face of a man who is one of the most grounded and rounded journalists this country has produced. And he knows how to make words sing.

He won’t tell you, but he’s got more gongs than he has tricky little ideas.

If there’s a heaven for editors it will have a newsroom full of Andrew Rules.

He writes sweetly and he can write about anything: sad, happy, silly, serious, complex, human. He is an editor’s dream because you can send him anywhere and know he will produce readable copy.

His investigative reporting is watertight. And you don’t need to read every sentence twice. Whether it’s the forensic demolition of a string-pulling crook, or a piece from a child’s funeral that makes you taste the tears, his writing unfolds, taking the reader with him. There’s no showing off, no preaching.

He has a sharp eye and uses it to draw sparkling word pictures. He has an uncanny sense of audience and writes for them, not the office whinger.

He sorted out secondary school in Sale but his life-forming break came after he twice won the Sale Agricultural Show essay competition, in 1973 and ‘74, collecting $5 a time.

Then, Andrew says, he decided he was too small to be a mounted policeman, too big to be a professional jockey (although he won a race as an amateur, just ask) and too smart and frightened to be a boxer or rodeo rider.

His career took him around the usual traps until as chief police reporter he was lured to The Herald as a feature writer and columnist.

Then came books, his first in 1986 (Cuckoo), time producing television, but certainly not on camera, a stint as a subeditor, and two years as a radio producer.

In 1994 he moved to The Sunday Age where two years later he won his first Perkin Award with a portfolio that included the Jennifer Tanner case: reporting that implicated a serving policeman in two suspicious deaths.

In 2001 there was another Perkin and the Gold Walkley for a superb expose that brought down the head of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), Geoff Clark.

This, Andrew believes, was some of the most important work of his career.

It is tribute to his professionalism that through his time he has moved around the available newspapers and is always welcome back.

In an era of bitter and at times senseless competition that’s no small tribute.

— extract of chapter by Neil Mitchell, former editor of The Herald, a reporter and news executive on The Age, and a leading broadcaster on 3AW since 1987.

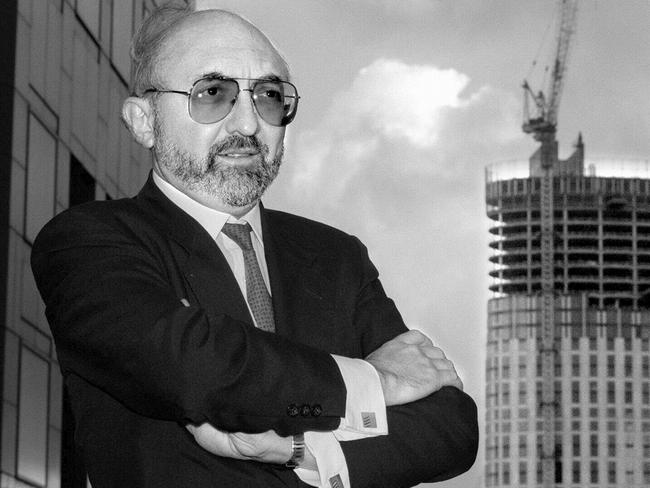

Terry McCrann

McCrann’s career in Australian journalism has been characterised by always being in the right place at the right time.

Back in the late 1960s, and after completing an economics degree at Monash University, he had planned to study law and become a lawyer.

But McCrann also had a side job at The Sun News-Pictorial — “taking the quotes” at the Stock Exchange of Melbourne at a time when the quote for each stock was actually called out and you watched and heard the traders trade each stock.

It was fantastic training and gave those reporters (including myself) a unique opportunity to understand markets.

In 1975 McCrann was made finance editor of The Sun.

He was then convinced by Max Suich, the then editor of the The National Times to leave The Sun and join The National Times. It didn’t work out and he left and took some time off. When he decided to return to journalism, both The Australian and The Age actively pursued him because both papers clearly recognised McCrann’s talent. He went to The Age just as his business editor James McCausland was appointed night editor and McCrann suddenly became business editor.

At that time it was becoming apparent that the big future in financial journalism would be in writing daily commentaries. And so McCrann thrust himself into that area. He had no sooner begun writing a daily commentary for The Age when the Ansett takeover battle emerged. This was a takeover battle the likes of which we had rarely seen.

It went on for months as the combatants Reg Ansett, Robert Holmes a Court, Peter Looker, Rupert Murdoch and Peter Abeles all played significant roles.

They all talked to McCrann and his coverage set him apart from the daily newspaper reporting of the event. In many ways the Ansett takeover really confirmed the role of daily columnists in financial journalism.

But Rupert Murdoch’s takeover of the Herald and Weekly Times was no less intense.

McCrann first met Rupert Murdoch in 1982 when he interviewed him after his first unsuccessful attempt.

When Murdoch secured control on the second attempt McCrann interviewed him again but this time Murdoch had a reverse agenda — he was also interviewing McCrann seeking to get him to join The Herald and new editor Eric Beecher.

The Age fought hard to keep McCrann. Murdoch won the day and McCrann became business editor of The Herald.

He had no sooner taken the role than the enormous 1987 crash took place. As an afternoon newspaper The Herald was not only able to be first with the crash details each day but McCrann was also able to lead the country in interpreting what was happening in New York.

After The Herald and The Sun merged, McCrann became business editor of the combined operation but his great love was being a financial columnist. The merger enabled his columns to be syndicated into the Telegraph/Mirror in Sydney plus the Brisbane Courier Mail and The Adelaide Advertiser.

McCrann suddenly became the most widely read business columnist in the country.

And he developed a skill of conveying business and investment journalism not just to the top end of town but to middle income Australia. McCrann took his ability to analyse and interpret corporate issues into politics, exposing misleading statements by both sides of politics.

— extract of chapter by Robert Gottliebsen, a Victorian Media Hall of Famer, the 1977 Graham Perkin Australian Journalist of the Year and a commentator at Business Spectator.

Laurie Oakes

His news breaking reputation ensured Oakes became a go-to person for those with a big story to get out.

When Andrew Wilkie decided to quit the Office of National Assessments in protest over the Iraq war, he left his card in Oakes’ letterbox with a note asking him to call.

Born in 1943, son of an accountant, Oakes studied Arts at Sydney University where he edited the student newspaper Honi Soit, first with Bob Ellis (later a well-known writer) and then, after beating Ellis at an election, solo. He was on a teacher scholarship but after reading a biography of renowned American publisher William Randolph Hearst, Oakes decided journalism “sounded like fun”. Hearst was the inspiration for Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, and Oakes was sometimes called “Citizen Oakes’’ by friends.

His first newspaper job was at The Daily Mirror in Sydney. At 25, he was appointed head of the Melbourne Sun’s Canberra bureau in 1969. National politics was in flux: the long term conservative government was in decline; Whitlam was starting his ascendancy. Change was in the air in the Canberra Press Gallery too; Oakes was part of a new “hungry’’ generation of journalists who would document one of the most exciting decades of federal politics.

Melbourne’s Sun, a huge-circulation tabloid that took politics seriously, was a great platform and Oakes’ reporting ensured it was a must-read for the political class. But by the later 1970s Oakes was ready for a move. He started a newsletter, The Oakes Report, and soon was persuaded into television, working first at Ten (1979-84), before moving to Nine, then in its heyday. There he had the ideal mix for many years: reporting on the nightly news, a feature interview for the prestigious Sunday program, and a column in The Bulletin.

Oakes’ strengths have always been his contacts, his attention to detail, and his ability to understand the wider context of individual events. Asked the story he’s proudest of, he names the 1974 Vince Gair appointment, to which he brought Sherlock Holmes-like deduction. He’d heard from a bureau colleague that a government appointment was in the air, but contacts were unwilling to say anything more than it was “big, big, big’’. Asking himself what could be that “big, big, big’’, Oakes concluded it had to be something affecting the government’s Senate numbers, and from that he guessed that Gair was the obvious target. He rang around putting the proposition to sources (the last being Gair’s wife) as something he knew, rather than surmised.

As a commentator Oakes is respected as tough but fair-minded; he can be scarifying but never uses a “scream’’ as an attention-seeking device. His very arrival can inspire fear in politicians. Seeing him (unusually) sitting at the media table when she addressed the National Press Club just before calling the 2010 election, Julia Gillard knew she was in for a bad moment and remarked on his presence. With a strong bulldust detector, Oakes has spiked more than a few politicians’ stunts over the years.

In television, Oakes brings the eye for detail that marks his writing, which in later years has been a weekly column for News Corp papers.

He pushes the deadline because he is always after the last fact; he’s competitive and secretive (cameramen can be sent out for shots not knowing what the story is). But he never assumes he knows it all, carefully watching what competing stations are doing. He’ll continually refine and sharpen the edge of a story, always looking for the best angle, writing for impact while maintaining accuracy.

Cameramen get exhausted looking for the shots, but they always want to work on Oakes’ stories because he gets the most out of their shots. In Nine’s Canberra office Oakes is high maintenance but revered.

Oakes has become one of the best known “brands’’ in Australian journalism. But he has never been part of the modern drift to self- centred “celebrity’’ journalism. His career has had a remarkable consistency in a changing industry, across platforms and through the years. His own story is one of notable power, used responsibly for the public good. His accolades include the 2010 Graham Perkin Australian Journalist of the Year, the 2010 Gold Walkley and a Melbourne Press Club Lifetime Achievement Award.

— extract of chapter by Chapter by Michelle Grattan, Media Hall of Famer, veteran Canberra political correspondent, Melbourne Press Club Lifetime Achievement Award winner and the 1988 Graham Perkin Australian Journalist of the Year

From Media Legends: Journalists Who Helped Shape Australia, Edited by Michael Smith and Mark Baker (Wilkinson Publishing) RRP $49.95. Available from Melbourne Press Club and book stores.

Originally published as ‘Media Legends: Journalists who helped shaped Australia’ reveals how giants in the game got their start