Mary Ann Nichols was the first of five women believed to be victims of serial killer Jack the Ripper

WHEN Mary Ann Nichols headed out in the early hours of August 31, 1888, to earn money for a place to sleep she had no idea she would become the victim of the most famous serial killer in history.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHEN Mary Ann Nichols was kicked out of Willmott’s lodging house in the early hours of Friday morning, August 31, 1888, she was undaunted. Nichols, known as Polly to friends and family, had spent her last penny on alcohol, but was confident she would soon find a man who would pay for her services or let her share his bed.

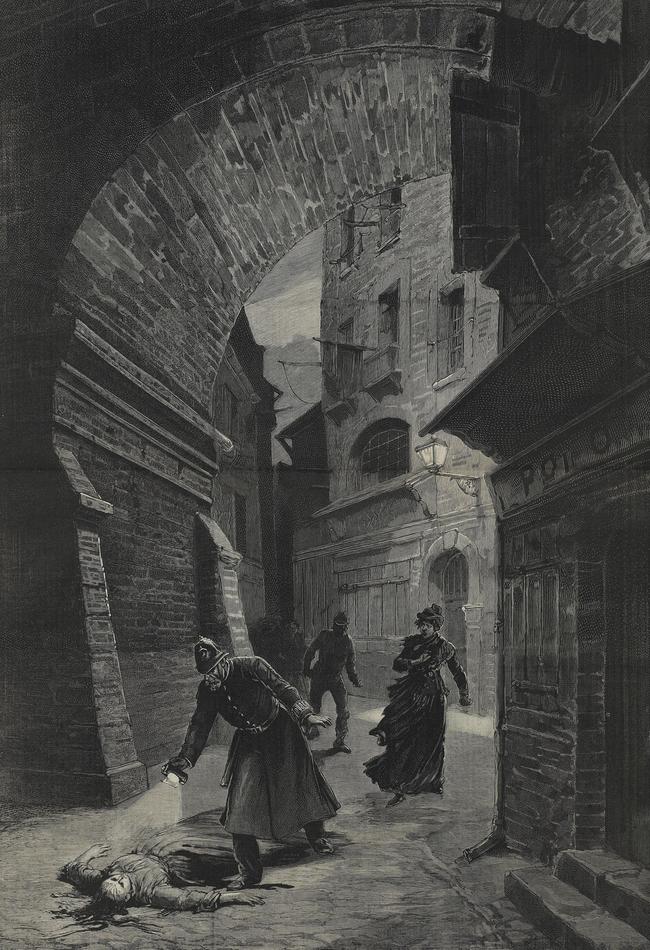

“Never mind,” she said. “I’ll soon get my doss money. See what a jolly bonnet I’ve got now.” She staggered out the door and walked the streets of Whitechapel. At the corner of Whitechapel Rd and Osborn St she met a lodging house friend, Emily (or Ellen) Holland, who pointed out that it was 2.30am and urged Nichols to go back to Willmott’s. There had been two women murdered in Whitechapel that year and it was dangerous to be out on the streets. But Nichols refused and headed off to look for a client.

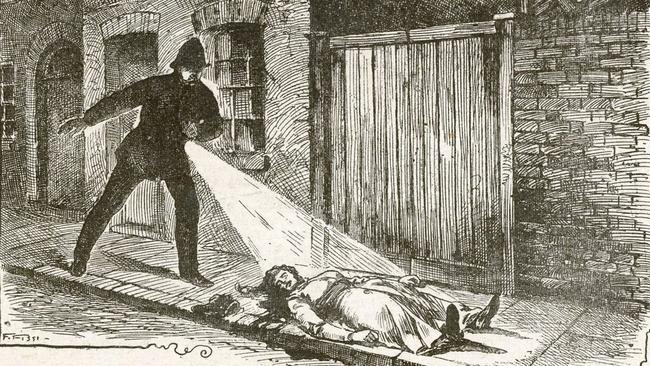

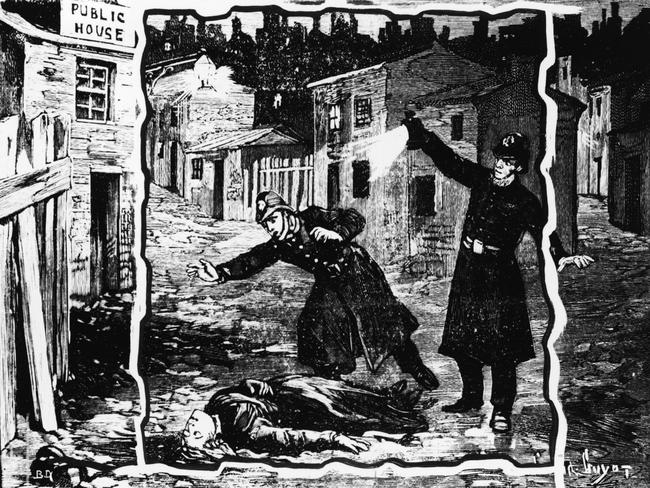

It was the last time anyone saw her alive. At 3.40am, 130 years ago today, Charles Cross was walking to work and saw something on the ground outside a stable. It was Nichols’ body.

He called over a friend Robert Paul. Cross assumed she was dead but Paul thought she was still breathing. They pulled her skirt down over her knees to preserve her dignity and left the scene to find a police officer.

Meanwhile, PC John Neil also stumbled across the body and alerted other constables.

Nobody knew it at the time, but this was the first in a series of killings by a man who would come to be known as Jack the Ripper. It sparked an intense police investigation under the command of Insp Frederick Georbge Abberline. However, the case has never officially been solved.

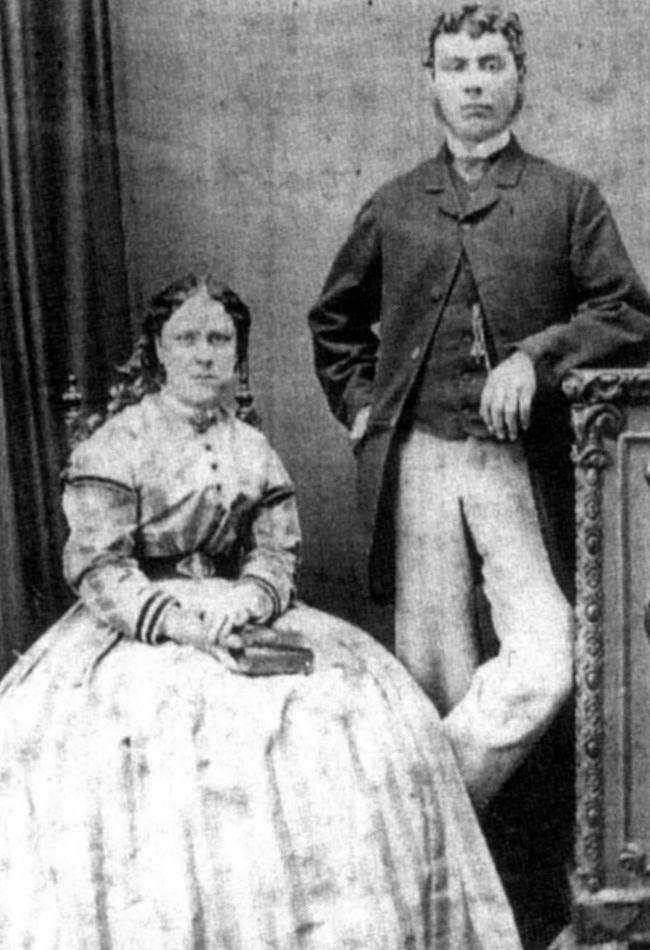

Nichols was born Mary Ann Walker in London in 1845, the daughter of a locksmith turned blacksmith.

She married printer’s machinist William Nichols in 1864 and they had five children but separated in 1881. She fell on hard times and ended up in and out of workhouses — places set up to house poor people, putting them to menial work.

Having failed to make a living as a domestic servant, she descended into alcoholism and was working as a prostitute when she was murdered in August 1888.

Police initially wondered if the crime was connected to one of two murders earlier that year; Emma Smith in April and Martha Tabram on August 7. But this killer had a different modus operandi. Nichols’ throat had been cut and her abdomen ripped open. But Smith had been beaten and raped with a blunt object, and died of peritonitis, while Tabram had been stabbed multiple times. Yet police couldn’t completely rule out a connection.

The next victim was Annie Chapman. Born Eliza Ann Smith in 1841, she married John Chapman in 1869. When their marriage broke down after both took to alcoholism, Chapman took to casual prostitution. Her body was found on September 8, 1881, her throat cut and body mutilated in a similar manner to Nichols. Because of the similarity, investigators linked the crimes.

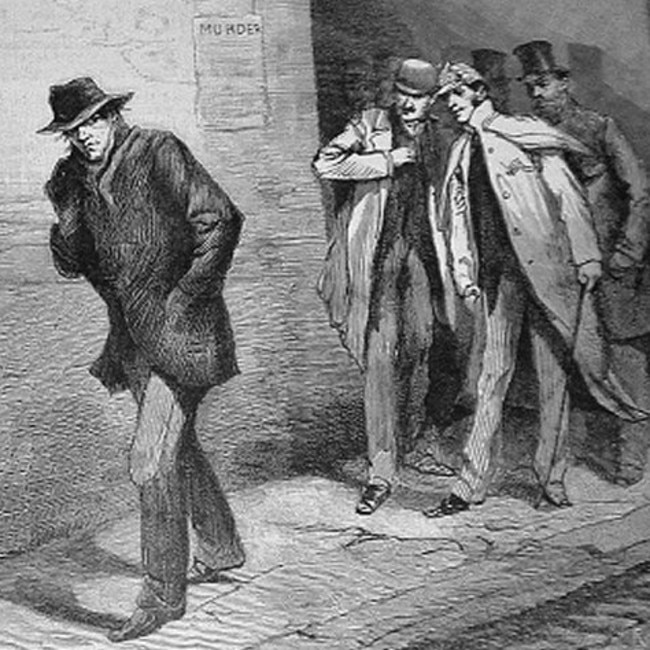

Two days later concerned citizens formed a Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, whose members volunteered to patrol the streets to protect women and look for the murderer.

On September 27 police received a letter purporting to be from the killer in which he said he was “down on whores and I shant (sic) quit ripping them till I do get buckled”. It was signed “Jack the Ripper” his trade name.

The bodies of two Swedish-born woman — Elizabeth Stride (born in 1843) and Catherine Eddowes (born in 1842) — were found on September 30.

It is believed the killer was disturbed while killing Stride, whose throat was cut but her body otherwise untouched. However, Eddowes was cut up more than previous victims.

A piece of Eddowes’ apron was found several streets away near graffiti implicating Jews (spelt “Jewes”). Police Commissioner Charles Warren had the graffiti erased fearing it might

spark reprisals.

When a postcard from “Saucy Jacky” was received by police on October 1, many doubted its authenticity. A letter “From Hell” received by the head of the Vigilance Committee on October 16 was also in a different hand to the first letter.

The final victim Mary Jane Kelly, born in about 1863 in Ireland, was much younger than the other victims. Believed to have been married to a coal miner who died in an explosion, before she went to London in 1884, her body was found on November 9 in her lodgings at Dorset St, Spitalfields. It was the Ripper’s worst case of mutilation, as he worked undisturbed behind closed doors.

Although there were other murders in Whitechapel, Kelly’s was the last attributed to Jack.

Abberline never got his man and people have speculated ever since who ended the lives of those five women.