WHEN he was seven, a psychologist asked him what his wishes were. “My wishes are killing more and more and more people,” the boy known as B replied.

“I wish I had a catapult that would hit someone on the head and then they would all be dead.”

In July 2013, a crowded South Australian Supreme Court gallery tensed as B, now 17, was led from the cells.

Everyone watching knew he was a killer - that he had stabbed and bashed a pensioner named Pirjo Kemppainen more than 120 times - but it seemed incongruous with the small teen swaggering to the witness box.

He wore a black suit and white sneakers, with dark hair cropped close around his large ears.

He had a face that, under other circumstances, might one day be considered handsome. Disturbingly, he rarely blinked.

Reminded of that long-ago psychological appointment, B frowned.

“I don’t remember saying that,” he told jurors, “but I’ve said it to friends.

“I was obsessed about killing people - from Year 1 to Year 8, I’ve just had thoughts about killing people. I still think about it.”

B’s testimony easily ranks among the most chilling moments in South Australian legal history.

His dispassionate evidence was as confronting as that of “bodies in the barrels” serial killer James Vlassakis, as unsettling as lust-driven killer-for-hire David Key.

Veteran police officers agreed that they had “never heard anything as bad” as B’s evidence.

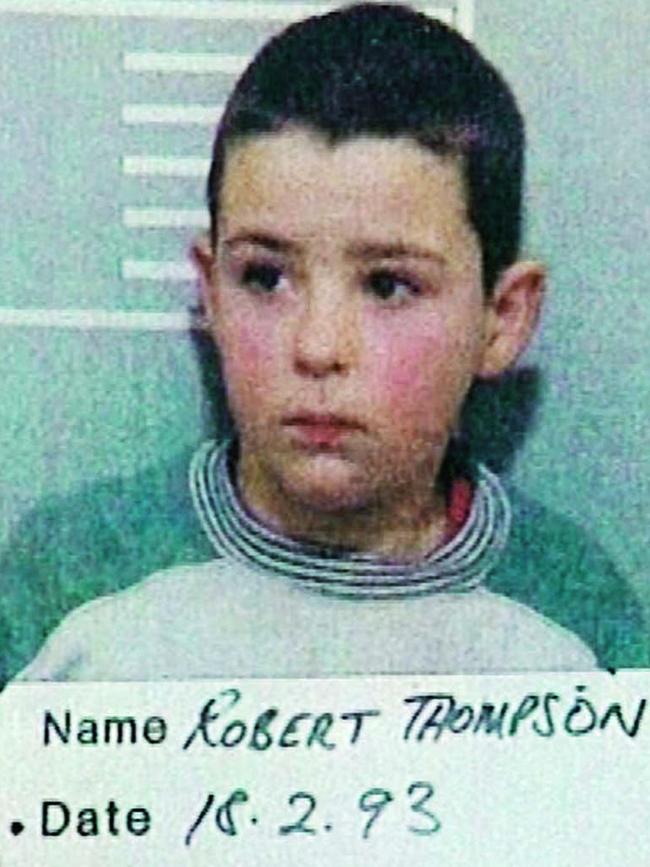

Ms Kemppainen’s murder - in the Adelaide Hills in the early hours of September 11, 2010 - dredged up unpleasant memories of the children who killed James Bulger and Anne Redman.

People asked how a boy, aged just 14, could commit such an unspeakable act.

Following the acquittal of his alleged co-accused, B’s story could finally be told.

B was born in August, 1996, to parents who soon separated.

“He’s been with his mother since birth,” B’s father told the Supreme Court.

“Wherever his mother was, that’s where B was.”

Forensic psychologist Luke Broomhall, who assessed B last year, found he had mild mental retardation, Year 2 literacy skills and intellectual function “in the extremely low range”.

“He is spectacularly unable to balance competing demands, brainstorm and come up with alternatives (to problems),” he said last year.

“If he had something on his mind he wanted to achieve, it would be very difficult for him to evaluate the consequences of that behaviour.”

B started watching violent movies at the age of seven, pornography at 10, and had a lifelong love of video games.

Asked about his hobby in court, B underwent a visible transformation - the surly, dispassionate killer gave way to an excited, animated boy. Such was his excitement that the court’s stenographers asked him to slow down because they could not keep up with his evidence.

“In Gears of War, you can cut people in half with your gun (which) has a chainsaw on it,” he enthused.

“You can blow people in half with a shotgun, strap grenades to people, use people as human shields, pretty well make mincemeat out of people.”

Mr Broomhall had noted this obsession and acknowledged research showing such games desensitise people to aggression and promote fighting over problem-solving.

“In some susceptible individuals, this can be a precursor to real-life events,” he explained.

“The key is that we’re talking about vulnerable people.” B, he agreed, was such a person.

The foundation for Ms Kemppainen’s murder was laid in 2008 when B’s stepfather accepted an interstate job.

The family moved - but the youth did not go with them, instead joining his father and his new partner in Kanmantoo, 5km north of Callington, several months later.

There were adjustment problems from the start.

In early 2009, some children knocked over the family’s rubbish bin.

“They were being smart arses,” B said in court.

“I got annoyed, so I got a meat cleaver and went outside and waved it around.”

His father’s new partner admonished him, to which he replied: “I should have capped their motherf...ing asses.”

His father’s relationship broke down in the middle of 2009, with the partner leaving, and B and his dad moved to Callington later that year.

B fared poorly at school, quickly becoming the target of bullying and teasing.

“His father encouraged him to take a stand if he felt he was being bullied,” Mr Broomhall said.

“He also encouraged a dislike or hatred of those who would seek to pick on him.”

The school worked hard to assist B, assigning a support officer to provide one-to-one care.

Wanting to help, she became an unwilling audience to his vicious ways.

The teen killers who shocked South Australia

B would spin knives on his thumb during home economics class and offer to murder her “old man” for $10.

“I know how to do it,” he explained, “I would go to the front door, I would wait until he opened it and I would kill him.”

Seeking to counsel - and defuse - him, the woman told B that people who do bad things get arrested.

“They won’t catch me,” he replied.

B’s true confidante was his eventual co-accused, a 14-year-old known as A.

According to B’s father, the duo spent every weekend together.

“They both loved movies and their games,” B’s father remembered. “What they were doing wasn’t of interest to me.”

It should have been.

“Every weekend, he was here, prior to the murder, I talked to him about killing someone,” B told A’s trial last week.

The friends would wander around Callington at night and throw rocks on houses to annoy their neighbours.

On Thursday, September 9 - two days before the murder - B asked a teacher: “How good would it be to see someone die?”

“I’m gonna stab someone,” he continued. “I wish I had a gun ... how good would it be to see someone being shot?”

The school took immediate action. A psychological appointment was organised for Friday, September 10 and B was closely monitored.

The psychologist never came - The Advertiser understands the appointment was cancelled because of a lack of resources in the region.

At lunchtime that day, the school support officer found B staring at a child across the playground.

“I hate that kid and I’m going to kill him,” he told her.

Before she could react, B ran across the playground and struck the child in the head.

His violence earned him an immediate suspension.

B responded angrily to his punishment.

“If you do this, people will die,” he told a teacher.

In Mr Broomhall’s opinion, the suspension sealed Ms Kemppainen’s fate.

“B’s primary motivation is to become empowered in any situation where he is disempowered, and by any means necessary,” he said.

“He experienced disempowerment and sanction in one setting, and so transferred it to a third party, an innocent victim, which allowed B to exact revenge.

“The murder was not about the victim, it was about B re-empowering himself.”

A slept at B’s house that night, expecting to go rock-throwing. B’s blood lust was up, however, and Ms Kemppainen would be dead before dawn.

“I put the knife in her stomach,” B told the court, pausing to mime the action.

“I tried to stab her twice in the stomach and then I repeatedly stabbed her in the head.

“She was screaming.”