They may no longer be on stage, but Li Cunxin and his wife Mary are still performing their very own pas a deux.

A year after the news that the beloved dancers would be stepping away from their roles at Queensland Ballet, Li as its artistic director and Mary as its ballet mistress, due to health reasons, the duo say they are in good shape, good spirits and, as always, in perfect step.

In June last year, the couple announced that Li had been suffering from heart issues for several months, while Mary had been undergoing treatment for gynaecological cancer, and both needed to focus on rest and recovery.

What the couple didn’t say then was just how serious their health issues were.

In Li’s case, he had both pericarditis (fluid and swelling around the heart) and atrial fibrillation (irregular and fast heart beat) which saw him collapse several times over a

six-month period from late 2022, be admitted to emergency 11 times, and eventually undergo surgery in January, 2023.

But it was Mary, Li’s wife of 37 years and a former world renowned principal dancer who, Li says, was “the main concern”.

For Li, known the world over as Mao’s Last Dancer after defecting from China’s Beijing Dance Academy in the late ’70s to join the Houston Ballet in the United States and go on to international acclaim, watching his partner in life and art struggle was far more painful than his own, broken heart.

“I wished I had the cancer instead of her,” he says simply.

In the dining room of their inner city Brisbane home, with its soaring ceilings, beautiful paintings, photos and mementos of their dancing careers from around the world, the couple are now sharing their full story, grateful to still “be here together”.

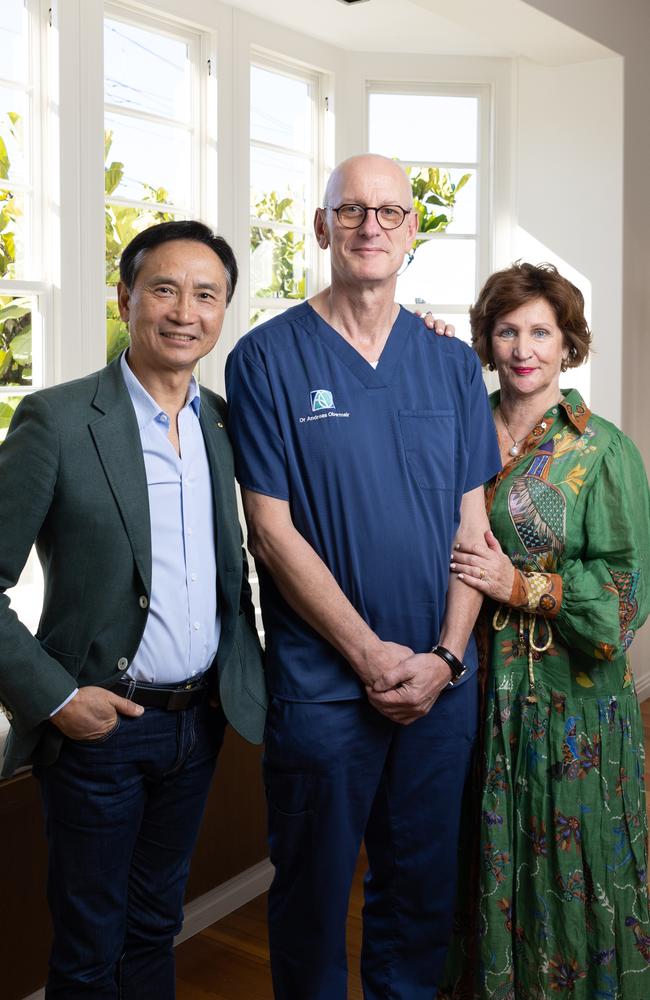

And for that, they credit the man sitting beside them at the dining table, Professor Andreas Obermair.

“He saved Mary’s life,” Li says. “We owe everything to him.”

Obermair, senior medical officer and director of research, gynaecological oncology, at the Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital, visiting medical officer at St Andrew’s War Memorial Hospital and professor of gynaecological oncology at the University of Queensland, has overseen every step of Mary’s treatment since her initial diagnosis in August, 2022.

He is also, somewhat serendipitously, a huge ballet fan. A Queensland Ballet season ticket holder, he says when he saw Mary and Li sitting in his waiting room in early September, 2022, he knew exactly who they were.

“When I saw them, I thought I’d have a heart attack, because no one warned me. No one. And I think I said, ‘Can you please sit down? I just need to get my nerves under control,’ Obermair smiles.

All three laugh, and it has been this sort of honesty that has earmarked the professional relationship between the three, with Mary also stressing Obermair’s genuine care for the women he treats.

“In this kind of cancer – gynaecological – my God, it’s imperative to have a very deep level of care and understanding,” she says. “He really cares about every woman he sees.”

That Obermair does care deeply for the women he treats is clear. In January, 2012, he founded Cherish, a not-for-profit organisation which raises funds for research and clinical trials to treat gynaecological cancer. Lesser known than other forms of cancer, it also attracts less funding.

“There are somewhere between 400 and 600 women diagnosed per year in Australia,” Obermair says, “but while it is very rare, the burden on women with the disease is absolutely enormous.”

There can also be a taboo associated with gynaecological cancer. It is, Mary notes, “a type of cancer that women can be hesitant to talk about’’. Which is exactly why she is now doing just that.

“In August, 2022, I had a small tumour taken out and about a week later, I was called and told it was cancer,” Mary says.

“I was also told that Professor Obermair was highly recommended, so I saw him very soon after that and he had me in the operating room the next day.”

Mary’s cancer was a rare type of skin cancer, vulva cancer, and as Obermair explained to her and Li, there were several treatment options available. This included the most common, standard treatment, which Mary, in consultation with Li and Obermair, opted not to have.

“After we did the tests to determine the extent of the disease, we had a conversation about options, and that’s a big thing for me because I don’t assume to know the life circumstances of my patients,” Obermair says.

Indeed, his medical research reflects this very human philosophy.

“Some of (the research) is addressing a deficiency, which is that at the moment we’re treating everyone pretty much the same. One size fits all,” he says.

“And the unwanted consequences of that is that sometimes we under-treat patients because we could do better. Sometimes we over-treat patients. So we need to develop the idea of precision surgery and to treat each patient as an individual, taking into account who they are and how they live their lives.”

In Mary’s case, the standard treatment on offer was definitely not a good match.

“Mary was very fit, very physically active, and with the standard treatment, the legs can be very compromised afterwards. One of the ways they are compromised is the legs get swollen, it’s called lymphoedema, and women with lymphoedema have great difficulty moving their legs.”

Mary shakes her head. “I said, ‘Well, I can’t have that.’”

Instead, after much discussion of alternatives, and to summarise what was a deeply complex process, Mary underwent an initial radical surgery, followed by two more surgeries, and three sets of radiation. Two sets involved 25 separate radiation treatments, and she also underwent brachytherapy radiation, which directly targets the tumour. It was a long and, at times, disheartening process.

“At one stage, when I came to the end of one of the 25 limited radiation treatments (as opposed to full pelvic radiation), the professor said, ‘Let’s just have a PET scan,’ and in the PET scan the cancer had metastasised, so he operated again and then I had full pelvic radiation.”

Remarkably – and to give an indication of just how unsuitable the standard treatment was for Mary – after her initial, radical surgery, she went on to dance the role of the Madam in Queensland Ballet’s Manon in September 2022.

Even more remarkably, Mary has been cancer free for a year now, but will require regular PET scans and ultrasounds of her pelvic nodes going forward.

As for Li, he says he has learnt to listen to his heart, in more ways than one. He too, danced in the 2022 production of Manon, in the role of Monsieur GM, and says that when he came offstage, he was unusually breathless.

“Looking back now, I see that was the first sign,” Li says.

“I remember saying to someone in the production, ‘Oh I must be so out of shape.’”

He wasn’t, but his heart was, and he kept dancing, kept up the exhausting business of making Queensland Ballet one of the most respected companies in the world, kept being the public face of it and kept pushing himself, as he always has, until his heart gave out, resulting in those 11 visits to the emergency room and his own lifesaving operation.

He and Mary’s health battles and subsequent step-down from their official roles at Queensland Ballet have meant a change of pace. They’re still dancing their way through life, but at a less frantic pace.

“It sort of stopped us mid track to ponder, to reflect on our lives,” Li says.

“We were running all our lives, striving, making things happen in our lives. And, for me, it was always the same speed, chasing another dream, another goal, and that was all wonderful, but this forced us to stop, and to think. I realised none of us knows what’s around the corner, so we need to start spending quality time together, and with the people we love.”

For Li and Mary, that meant spending more time with their three children, and with a few old friends. The couple went to China in January this year, travelling on the Queen Mary 2, with a stop in Hong Kong on the way.

They visited Li’s old ballet teacher in Beijing and Li’s best friend, who readers of Mao’s Last Dancer, Li’s best-selling autobiography, know and love as The Bandit.

They visited Li’s family in his hometown of Qingdao – Mary worried that they were being spied upon by the communist government, Li noting he was “more relaxed, just very happy to see my friends”.

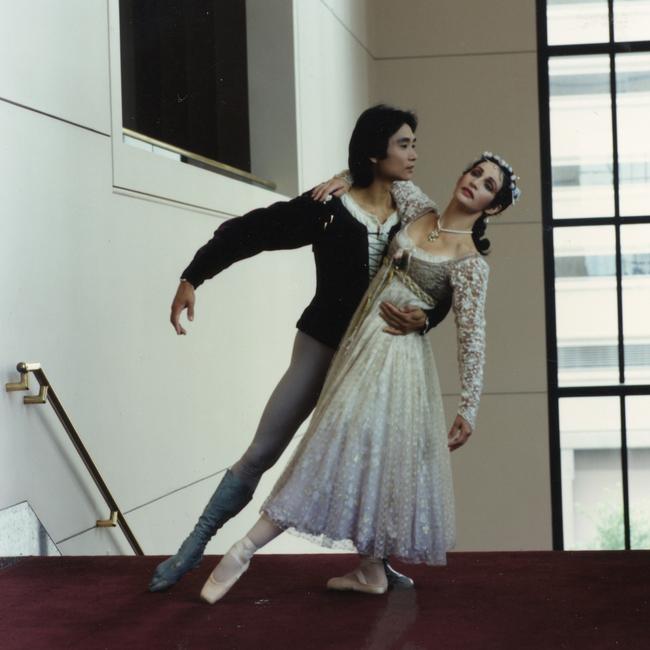

In May they travelled again, to Houston in the US, to see their old mentor and former artistic director of the Houston Ballet, Ben Stevenson. Both Li and Mary were his principal dancers, and it was on his stage during the ’80s that they fell in love. Li smiles.

“It was wonderful to see him,” he says.

“Then we saw Charles Forster, the immigration lawyer who saved my life at the consulate all those years ago, and they did a screening of Mao’s Last Dancer. Ben and Charles and I did a Q and A afterwards and it was very special, and very emotional.”

The couple also travelled to New York, and next year will go to Lausanne. In short, they are doing everything they said they were going to do when they stepped down from the ballet.

With one exception. They are also lending their names, their reputation and their unmatched ability to open doors and raise funds for Cherish.

Still very much a part of Queensland Ballet, and happy to “do what we can, when asked” for the company, the couple say supporting the ongoing research for Cherish, particularly for clinical trials, has also become very important to both of them.

“Andreas is someone we both admire so much, and not just because he saved Mary’s life, but because of the way he supports the women who need his expertise,” Li says.

“In the same way I agreed to come to Queensland Ballet to establish it as a world-class company, I feel that when you have someone like Andreas and his team, the level of talent he has, when you support him, he will be able to conduct his world leading research and attract other talent to help with the research. One thing I know from my own experience is that talent attracts talent.’’ And like attracts like.

For the professor, meeting Li and Mary in the waiting room that day was to meet two very like-minded souls. Passionate. Caring. Daring. Determined. And ready to step up.

“We founded Cherish in May 2012,” he says.

“It came about because research funding for gynaecological cancer is very sporadic and very patchy. We needed to establish a fundraising entity that supports the research unit that doesn’t attract many grants. With the support of Mary and Li, some 10 days ago Cherish pulled off an enormous luncheon event with about 250 people in attendance (at Brisbane’s Calile Hotel). And that raised an enormous amount of money.” He smiles, still slightly incredulous.

“We’ve never seen this before.”

For Mary, helping Cherish means not just helping the man who saved her life, but all the other women like her.

“The luncheon was so moving because Professor Obermair spoke about some of the women he has treated. Young women. Pregnant women. One woman was 86 years old,” she says.

Li Cunxin smiles at his wife, and the professor beside her. He feels grateful, he says, to be here with both of them. He feels incredibly grateful, he says, that he and Mary’s dance, against some pretty formidable odds, goes on.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Santos approves $30bn takeover from Abu Dhabi consortium

The deal includes promises to maintain Santos’ headquarters in Adelaide and accelerate investment in gas in Australia, should it go through.

Qld real estate agent fined, banned for 10 years

A Queensland real estate agent has been fined and banned from holding a real estate licence for 10 years following an investigation by the Office of Fair Trading. Here’s why.