How the Kellogg brothers influenced the way westerners eat breakfast

DIETICAN Lena Cooper was the first person to say that breakfast is the most important meal of the day.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AN article by American dietitian Lenna Cooper printed in 1917 suggested that “breakfast is the most important meal of the day”. The article appeared in Good Health, a magazine published by the Battle Creek Sanitarium in Michigan, which was run by Dr John Harvey Kellogg.

Both Cooper, through her catchy saying, and Kellogg, through the invention of flaked cereal — 124 years ago today — have had a major influence on breakfast in the western world. Cooper, who was mentored by Dr Kellogg and conducted nutrition classes at his sanatorium, was influenced by Kellogg’s food philosophy. In August 1917 she wrote that “less attention is usually paid to breakfast … yet in many ways it is the most important meal of the day, because it is the meal that gets the day started”.

Breakfast was on the menu this week when radio host Jackie O revealed she skips breakfast in the effort to keep trim, and a judge threatened to abandon a trial because the defendants were “too light-headed” to testify because of an inadequate morning meal.

Dr Kellogg would have been dismayed, because he and his protege Cooper had very definite ideas about the first meal of the day. Yet before Kellogg arrived some societies had never bothered with breakfast.

Most ancient people didn’t eat three meals a day, many ate only two. In ancient Egypt, for example, people often rose early and only ate after either offering prayers to the gods or doing essential farm work — in many cases at midday.

Those who had to eat usually based their meals on grains. The ancient Egyptians only ate two meals; a simple one in the morning before work mainly of bread, possibly with some seasonal fruits, and in some cases onions, with jams, honey or savoury dips, washed down with beer. Some enjoyed bread with a dish made of beans, oil, garlic and spices, which is still enjoyed today. The second meal, in the evening, probably included meat and, in richer households, wine.

Ancient Greeks called the first meal of the day ariston, but mostly ate at noon. Again it was largely bread, but dipped in water, wine or oil to soften it. They also ate olives and cheese with the bread. In The Odyssey, ancient writer Homer describes a morning meal of platters of meat left from the previous night’s dinner, plenty of bread with a cup of sweet wine.

While ancient Romans also ate bread, olives or leftovers for breakfast, the stoic philosophers believed eating more than one meal a day was gluttony.

In medieval times breakfast was often skipped altogether, instead most people ate at 11am after working from sunrise. Only the sick and the old were encouraged to eat a medicinal morning meal, usually a porridge made from grains, or even peas, mixed with water and boiled. In Old English it was known as morganmete, or morning meal.

By the 16th century the word “breakfast” entered the vocabulary and the culture, thanks partly to a 1515 statute introduced in England requiring labourers to start work at 5am. In the 18th century when the agrarian revolution forced more workers away from farms and into cities where they had to conform to a schedule, people started to eat breakfast more regularly. The menus varied; many ate porridge because it was quick and relatively cheap, some ate bread and water for the same reason. But in well-to-do households eggs and meat, such as sausages and kippers, were preferred, along with toast, muffins or crumpets and jam.

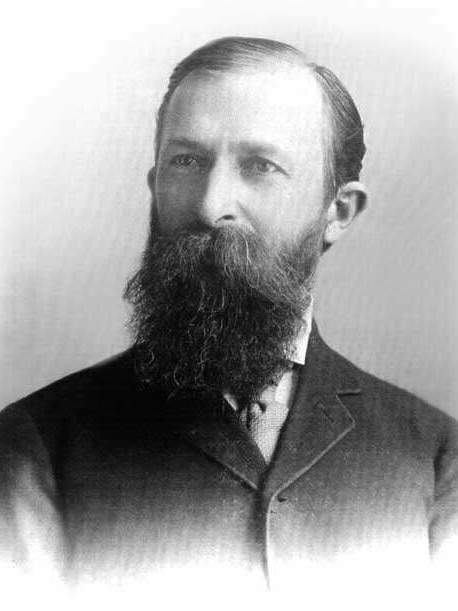

But in the 19th century when heavy breakfasts played havoc with digestion and general health, “experts” suggested dietary cures. Many were Americans, such as Adventist James Caleb Jackson who believed in vegetarianism. He invented what is considered the

first pre-prepared breakfast cereal named granula — nuggets of dough made from Graham flour (coarsely ground whole wheat grains) that were soaked overnight to make them soft enough to eat.

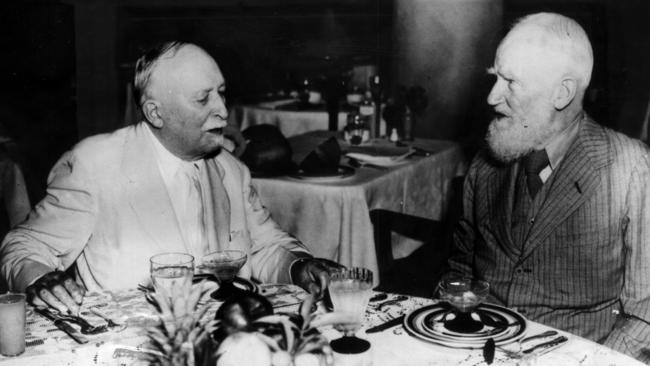

Dr Kellogg, also an Adventist, liked the idea but improved it by adding softer grains and breaking it into smaller crumbs. He called it granula too but changed it to granola to avoid legal action. Looking for other ways to feed grains to the patrons of his sanatorium, on August 8, 1894, his brother William Keith Kellogg accidentally stumbled on a way to make wheat into flakes. Later the brothers did the same with corn.

William later went on to found a cereal company that made cornflakes one of the most popular breakfast foods. Aggressive marketing campaigns backed with “expert” opinions, like those of Cooper, helped sell the idea that cereal was the ideal food to eat first thing in the morning. However, in recent times nutritionists have caused us to rethink that notion.