Hero cop who shot Lindt gunman Man Monis speaks for first time about the siege

On the 8th anniversary of the horrifying and tragic Lindt Cafe siege, the man responsible for killing Man Monis has revealed for the first time what unfolded that day and the devastating impact it has had on his life.

Special Features

Don't miss out on the headlines from Special Features. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The day started like many others. I had been on call for the weekend and had given a mate a Monday morning lift to work.

He was a solid operator and an experienced sniper.

The two of us burst through the front door of our office on Goulburn St, Surry Hills at 6.30am, still chatting about politics.

We call our headquarters building “the bunker”. The back of the building looks like reconstructed Stalingrad – bleak and functional.

The front looks much the same but, with some huge trees, and an excessively large, bold, and silver-coloured capitalised sign that reads SYDNEY POLICE CENTRE (a favourite media backdrop for television talking heads).

After coffee and my standard wellness check … I walked back through the front door of the office and instantly felt that something was wrong. A police negotiator sprinted past me. I couldn’t recall ever seeing a “neg” moving quickly, let alone running.

“There’s a counter-terrorism job at Martin Place. Grab your gear, we’re going now!”

“Oh shit! So, it’s finally happened?” I called back. We all knew it was just a matter of time, especially since the 9/11 attacks in the US.

■ ■ ■

After 2001, the TOU were regularly briefed by the Joint Counter Terrorism Team (JCTT). This was made up of NSW Police, the Australian Federal Police, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) and the NSW Crime Commission.

Recently, I’d been part of the JCTT-run Operation Appleby, the largest job of its type in Australian history. Simultaneous pre-dawn search warrants were conducted by over 800 police officers across NSW and Queensland, resulting in 15 suspects being detained on terrorism-related offences. A cell comprising returned ISIS fighters – and many others –was planning attacks on the Australian Federal Police building in Sydney, the NSW Sydney Police Centre, where we work, the Garden Island naval base and Parliament House in Canberra. Orders issued directly from the ISIS leadership inspired advanced plans to kidnap a random civilian off a Sydney street, before beheading him or her and live-streaming the brutal attack on social media. The Endeavour Hills stabbing of two police officers by a terrorist in Melbourne, only weeks before, was also on our minds.

For these reasons, the threat level at the time was ‘critical’, meaning that another attack was considered imminent.

■ ■ ■

Back at the Sydney Police Centre, I followed him into the lift. Nothing was said. We ran to the TOU secure storeroom, where I quickly donned my full kit, before jumping into the back of the BearCat armoured vehicle. (We) drove at speed under lights and sirens while I loaded my M4 assault rifle.

Screeching to a halt in Elizabeth Street, I jumped from the back of the BearCat and ran to the corner of Martin Place. There were cops everywhere — and even more television cameras. A large group of onlookers were already being moved on by general duties officers. The team leader was talking with one of our inspectors and other operators. I received a brief version of events as more information was coming in by the second.

He confirmed: “An unknown male has entered the Lindt cafe with a shotgun and claiming to have a bomb. He’s taken all occupants hostage.”

■ ■ ■

The highway patrol officer who responded to the initial triple-0 call provided us with a clear description from his earlier observations through the glass foyer door: “A man of Middle Eastern appearance in dark clothing, holding a shotgun and wearing a black backpack with wires hanging out.”

The POI had chosen his location well. The Lindt cafe is in the heart of Sydney, with the Reserve Bank of Australia and the Channel 7 media building directly opposite. The city was shut down. From that moment the siege was live-streamed around the world on all major national and international television networks.

The team leader reported, “The POI ordered the manager of the café, a 34-year-old man, Tori Johnson, to contact emergency triple-0 and read out this message: ‘Australia is under attack by Islamic State. There are three bombs in three different locations: Martin Place, Circular Quay, and George Street. Police should not come close to me or other brothers, otherwise they will explode the bombs. Some hostages have been taken.”

The inspector then added, “Our snipers have confirmed that there are hostages positioned across four windows. Two of them are holding black flags with white Arabic writing, blocking a clear view.” There were three separate sniper teams embedded. The first was in the Channel 7 building opposite the Martin Place side of the café. The second was in the then Westpac Bank building opposite the front entrance door on the corner of Phillip Street and the third was in the Reserve Bank of Australia building.

■ ■ ■

The entire area had been evacuated. An eerie silence ensued with pieces of rubbish blowing past and along the otherwise bustling but now empty streets, past Martin Place’s prominent faux sandstone bollards, blocking vehicular access and on to the dark-grey pedestrian promenade. Abandoned cars lined the asphalt walkway to the side of our position. The only sounds were the monotonously regular beeping of a nearby pedestrian crossing and the distant wail of police sirens echoing off the surrounding skyscrapers.

Everyone was ordered to remain in position and like a great many other TOU jobs it was a case of ‘hurry up and wait’. The time was now 12.30pm and we’d been on site for nearly three hours. It was summer in southeastern Australia and the weather was typically hot and humid. An update was broadcast over police radio that the terrorist or ‘Tango’, had taken 18 hostages but was refusing to speak with negotiators. Beyond this, from our position on the front line, there was an immediate lack of operational intelligence on what was occurring inside the café. This was because every member of the TOU sniper team’s vision was obscured by a combination of human shields holding up flags against the cafe’s windows and heavily stencilled festive sign-writing proclaiming: ‘Lindt – Merry Christmas’.

I needed to know what was happening inside the café. We discussed our concerns before I approached (the team leader). “There’s been nothing come in for hours. Do you reckon we could push forward to that first window and have a look in?” We were exasperated. We needed a plan.

“Righto,” he surprisingly agreed. “But keep your guns up and try not to be seen.”

“Thanks,” I responded with relief. “Let’s go. I’ll cover you.”

He slowly eased forward with the shield held close to his face, peering through the distinctive rectangular bullet-resistant glass viewing port. I was on his left shoulder with my rifle up ready to respond. We pulled up to the first of the four windows and peered in. The very first thing I noticed was an extravagant display of Lindt chocolate balls of all colours and types. It reminded me of the brightly decorated Christmas tree that my wife and I had set up at home that very weekend. I looked beyond one of the imposing green marble columns to where two female hostages were holding flags up to the windows. (Only two of the four windows were visible from our vantage point.) This confirmed what had already been reported by our snipers. Some hostages were seated and visibly upset. No one was talking or looking at each other. I clearly observed one young woman in a Lindt cafe uniform: a black long-sleeved collared shirt, long trousers, and a maroon-coloured apron with gold lettering. She seemed to be on autopilot, oblivious to what was happening around her, serving drinks from a tray to other hostages. It was surreal.

Then the terrorist suddenly appeared, before ducking behind a hostage. He was wearing a black bandana with white Arabic writing on it and holding a pump-action shotgun — a Manufrance La Salle, with both the stock and barrel crudely sawn off.

What was more concerning, however, was the backpack he was wearing. I looked at it very, very closely. The black Camel Mountain bag was stretched by its contents and I could see two wires looping out of the bottom — one black and the other red. “Are you seeing what I’m seeing?”

I asked.

“Yeah, that backpack definitely looks like a bomb.”

“Can you see the wires?”

“Confirmed. Not good.”

“F--k no!”

Only weeks before, a specialist from the Australian Army’s Special Operations Engineering Regiment had shown us how to identify improvised explosive devices or IEDs so this was fresh in our minds. The tutorial included the types of bombs terrorists were currently using around the world: pipe bombs, shoe bombs, underpants bombs, suicide vests and the sort of backpack bombs that started to appear in early 2005. The operator also showed us some physical examples. I had a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach. What I was observing looked just like the CCTV images of the backpack bombs that detonated in three London Underground stations and on a double-decker bus, killing over 50 people.

I knew that a bomb comprising a backpack full of easily obtained explosive material could vaporise everyone in the immediate vicinity — including us — and potentially bring the entire building down. For this reason, every floor above the cafe had been evacuated, as well as surrounding buildings. Was it the terrorist’s intention to draw us all in and then detonate the device?

■ ■ ■

I reported my intelligence precisely in person, who then relayed it to senior officers in the command post set up in the NSW Leagues’ Club on Phillip Street. After consideration, the bosses requested further details. We took turns staring through the ballistic-shield viewing port at the terrorist prowling around the cafe for some 25 minutes – undetected, paying careful attention to both the shotgun and the backpack. We also counted how many

hostages were in the room and then recorded both their descriptions and locations so that they could be individually identified.

The team leader came forward. The three of us agreed that the shotgun was a pump-action 12 gauge – and likely to have a four to five round rapid-fire capacity – a formidable close-quarters killing machine. (The team leader) looked at me with his eyes wide open and then nodded in silent agreement; he also confirmed seeing the backpack and wires.

I looked closer at the women holding the standard black banner with white Arabic script — the jihadist flag used by Islamist groups like ISIS. It said: “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is the messenger of God”.

One of the women was shaking and sobbing. The Tango continued to pace around the cafe shouting at hostages. We noticed that whenever he left his base at the far corner of the cafe, he always had a hostage in front of him with the shotgun pushed into their backs. He was clearly conscious of being exposed to any of the windows and ducked when walking past them.

The terrorist appeared to be directing most of his abuse towards a male hostage dressed in a sharp, black, long-sleeved shirt, long black pants, and black polished boots, contrasted by styled blonde hair. The man clearly displayed a sense of calm, dignified composure. I now know him to be the cafe manager, Tori Johnson.

The Tango’s human shield of choice, however, was a middle-aged, heavy-set, kindly-looking woman with fair skin and short, light brown hair, who I now know to be Louisa Hope. All we could do was watch as he frogmarched her around the cafe. Although visibly upset, her self-control seemed to enrage him. My determination to protect the hostages and neutralise the threat was growing by the second.

I then observed a young man with a fop of dark hair, who I later knew to be 19-year-old Jarrod Morton-Hoffman. He was talking on a mobile phone with the terrorist standing over him yelling instructions. The poor guy seemed to be holding up well under pressure although he was visibly shaking. When it was (my mate’s) turn to observe the situation, the young man bravely pointed out where the terrorist was, even using a hand signal to confirm that the Tango had a gun. This impressed us.

The terrorist unfortunately noticed Jarrod and turned towards us. Our eyes met and the realisation of just who he was looking at hit him — two heavily armed and determined trained assets. He immediately crouched low, pointing his weapon in our direction, before lunging towards Louisa Hope, grabbing her by her blouse, violently manhandling her to her feet and pushing the barrel of the shotgun into the back of her head. I could see that his finger was on the trigger. The expressions on the face of every hostage screamed: ‘Why won’t you help us?’ The truth was that we were just as desperate to go in. At that moment, the terrorist became incensed. Louisa Hope was in grave danger. Suddenly a hand appeared, placing a rough handwritten note against the window in front of us – an action obviously dictated under duress: ‘Police move away now, or a hostage will be executed’. We immediately withdrew from the window.

■ ■ ■

Suddenly, an elderly hostage burst through the front door of the cafe. Clearly driven by raw self-preservation, the man turned to his right and stared in our direction like a rabbit in a spotlight. A younger man dressed in smart suit pants and a perfectly pressed long-sleeved white linen shirt followed closely behind him, flapping his hands in the air hysterically. The stack pushed forwards to provide cover.

“It’s the police. Come over here!” They both had a look of blind terror in their eyes.

As our stack regrouped, the fire door directly in front of us suddenly swung open, this time with a loud crash. A middle-aged man, with a dark receding hairline and manicured eyebrows wearing a Lindt cafe uniform, abruptly appeared. He immediately tripped and stumbled before we pulled him to safety as well. The man seemed even more overwhelmed than the others, barely able to understand basic instructions, repeatedly shouting: “You need to get in there, you need to get in there, he’s going to kill everyone!” In over 12 years of frontline policing, I’d never seen human beings in such a state of distress, panic or shock.

■ ■ ■

I checked my phone and saw the missed calls and messages from family and friends. I browsed quickly over some of them. Despite wearing a tactical helmet and balaclava, a lot of people had recognised my eyes from the close-up television footage.

The reason I wasn’t wearing my work sunglasses was that our two-year-old daughter had broken them. My wife later told me that our little girl had also recognised me from the live-streamed footage. “That’s my daddy,” she said giggling, pointing at the flat screen television. That was enough for my wife. She turned it off straight away.

■ ■ ■

At different times throughout the day, the situation ramped up to the point where I believed we were about to go in, before being ordered to stand down again. It must have been what it was like for the Diggers waiting to go ‘over the top’ in Gallipoli or in France. In those moments of down time, we talked.

“You guys realise that, when we storm in there, we’re all going to be worm food, don’t you?” (my mate) blurted out.

The brutal reality, as we saw it, was that as soon as we entered the cafe, everyone was going to die in a massive IED explosion. In that moment, this inevitability hit us all like the proverbial Mack truck. Our training had incorporated strategies for deliberately putting away distracting feelings about being killed, but now death seemed almost a certainty. No one spoke. We just stood there, our rifles at the ready, shoulder to shoulder, ready to go, waiting for the ‘whistle to blow’, deep in our own thoughts.

A bomb meant that there was only a slim chance of getting any of the hostages out alive and every frontline TOU operator would die too. I texted my wife, trying not to let her know what I was thinking, asking her to send me some recent photos of our little girl. I showed my mate, who reciprocated by scrolling through photos of him playing with his boys. (Meanwhile, one of the others texted his wife: “Don’t forget to put the bins out.”)

As I gazed over my pictures, a feeling of deep sorrow washed over me. I was resigned to the idea that I was never going to see my wife and daughter again and I wasn’t ever going to hold the unborn baby that she was carrying, let alone see the rest of my family and good friends again. I said my goodbyes through text messages as best I could, without revealing our exact predicament. But I’m sure my wife knew exactly what was going on. I encountered many brave women that day but none braver than the woman I loved.

Then, one of the TOU guys in the stack suddenly went white; he obviously couldn’t handle it. I could see it in his eyes. The harsh reality of the situation had clearly overwhelmed him. I watched and didn’t say a thing. Everyone had done the same selection and training courses, but the truth is no one really knows how they will hold up until their big test comes.

■ ■ ■

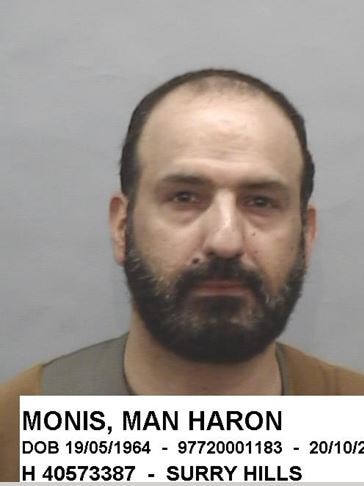

The terrorist was finally identified. (The team leader) was sent an intelligence brief on his smartphone. The man was a self-proclaimed Islamic cleric, Man Haron Monis, a 50-year-old Iranian-born refugee, currently on bail as an accessory to the murder of his ex-wife by stabbing, together with 43 outstanding charges, including 22 counts of aggravated sexual assault and 14 counts of aggravated indecent assault. (In April 2001, the INTERPOL contact point in Canberra had alerted the Immigration Department that Monis was also wanted by the Iranian authorities.) Locally, he’d obtained notoriety in the media by sending hate mail to the families of Australian soldiers who had died serving their country in the war in Afghanistan. Only a month earlier, he’d pledged allegiance to Islamic State on his website and then again on social media. “That’s him, right boys?”

(The team leader) questioned, holding up his phone to show a photograph.

“Yeah man, that’s the grub,” I confirmed.

“Shit, what’s he doing out on bail? Someone has seriously f--ked this one up,” (my mate) added, stating the obvious.

■ ■ ■

The terrorist was still refusing to speak with police negotiators, only ever communicating through hostages, demanding via the media that police and politicians acknowledge that his action was an attack by Islamic State. He even forced a hostage to call the broadcaster Ray Hadley who, to his credit, wouldn’t allow him to talk on air. A report then came in that he was demanding an actual ISIS flag. He was also insisting on talking to Prime Minister Tony Abbott.

Persistent postponing of his demands was clearly increasing his emotional temperature, or at least that was obvious to us. Then two more female hostages suddenly escaped. They’d snuck out through the foyer. I had a growing concern that a humiliated terrorist would be forced into a decision and then, according to what we believed at the time, execute his final act – an internationally-televised extravaganza of death and mayhem that would have energised ISIS lone wolves all over the world for a generation.

Senior commanders were, however, sticking to the longstanding ‘contain and negotiate’ strategy that had served them well up to this point. It must have seemed to them that most of the hostages were eventually going to escape by their own means – and that time was on their side – but it wasn’t on our side, it was not what was needed, not what we wanted and not what we were trained to do – which was to aggressively seize the initiative at an exact time and manner of our choosing and, in doing so, save the hostages.

■ ■ ■

Darkness fell and the situation became increasingly frustrating for us – and dire for the hostages. All we knew was this had gone on too long. Still, I wasn’t concerned about the terrorist and his shotgun. I was confident in our abilities to deal with that threat. The big issue was always the bomb. Command, like us, believed that, if we did anything to provoke the terrorist, such as make entry or have our sniper take a shot, then he would more than likely detonate the device and every one of the remaining hostages in the cafe would die.

Despite many in Australia having an opinion on the matter, a sniper shot would have had huge repercussions. The terrorist was very careful not to expose himself to windows but, if he had to, he would always hold his shotgun to a hostage’s head.

When shot, the body’s natural reaction is to spasm in a jerking reflex contraction. I was a trained sniper myself and aware of this happening in both hostage rescue and battlefield situations. The only way to counteract this is to shoot the ‘apricot’ (the medulla oblongata or brain stem), which immediately results in total nervous incapacitation. Under the circumstances, it was a near impossible shot – and then, of course, we later found out the cafe glass was bullet-resistant.

■ ■ ■

As 2.00am approached, something came in over the police radio. It was senior command assuring us that ‘things were settling down for the night’.

“Settling down for the night? Settling down for the night”? I said out loud twice because I couldn’t believe hearing myself say it the first time.

“What the f--k do they think is happening in there? That he’s slung a f--king hammock and is having a little f--king nap or something,” my mate said with genuine confusion in his eyes.

“How can they think that? So, he’s just going to wake up all fresh in the morning and clock back on to his day job as a f--king terrorist?” I said shaking my head.

Our entire frontline team was frustrated beyond words. There was also a general feeling that we’d soon be swapped out with standby operators or the out-of-state boys. Then the battery in my police radio went flat. This added considerably to my frustrations. I couldn’t see inside the cafe and now I wouldn’t be receiving radio updates. But I thought to myself, it didn’t matter anyway because senior command believed that the situation was ‘settling down for the night’.

Then boom. “What the f--k was that?” yelled one of the other operators from behind me in the stack. (My mate) called out, “Shot fired, shot fired.”

“That was a f--king shotgun going off inside the cafe. Oh f--k, the hostages!” I yelled.

READ MORE OF ‘TIGER, TIGER’ IN THE NEXT BOOK EXTRACT WITHIN THE SUNDAY TELEGRAPH.