German sailors’ mutiny sparked a revolution that ended one destructive war, but laid seeds for another

WHEN sailors at Kiel Canal refused to take part in a do-or-die naval battle on October 29, 1918, it sparked a revolution that ended one destructive war, but laid seeds for another.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

BY October 1918, Germany was tired. After four years of war most of its population was sick of the privations; those in the armed forces were exhausted from years of fighting. Many believed the government and the military had let them down and that it was time for a change of leadership.

Some in the military were not ready to give up. They believed that nationalist fervour and a resolve not to let the fatherland fall, were the elements that would see them prevail. But they could no longer depend on blind obedience.

On October 24 the German high command ordered ships in the naval fleet head to the North Sea for a battle against the British Grand Fleet. But on October 29, 1918 — a century ago today — the sailors at Kiel Canal, in the German state of Schleswig-Holstein, refused.

The open mutiny spread across Germany, leading to a revolution that toppled the Kaiser and brought the war to an end. Ultimately it was quashed and key revolutionaries were executed but it would spark the “stab-in-the-back” myth that Germany’s military had been betrayed by its civilians and elected government, a notion used years later by the Nazis to attain power. So while the revolution ended one destructive war, it laid seeds for another.

The revolution had its origins in the powerful socialist and labour movements that emerged in Germany in the 19th century. Germany was the birthplace of Karl Marx, the most influential socialist theorist.

In the years before the war, despite Germany’s apparent depth of conservatism, the Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands or SPD) had grown to be a major player in the Reichstag. At the outbreak of World War I most of the SPD supported the war.

Left wing member of the party, Karl Liebknecht, split with the SPD over their support for the war. In 1914 he formed the Spartacist League with several other prominent socialists including Rosa Luxembourg. Liebknecht organised protests against the war, but in 1916 was thrown into prison after he was arrested at one his protests. When he was released on October 23, 1918, the world was very different.

In Russia the Tsar had been overthrown and the communists were in power, leading Liebknecht to believe it was only a matter of time before the same happened in Germany.

The German government was already discussing peace terms and one demand of the Allies was the introduction of constitutional monarchy. A resolution was passed in the Reichstag and ratified by the Kaiser to say that the Chancellor could not make decisions without its support.

But with Germany continuing its unrestrained submarine warfare, the Allies were not satisfied and instead made demands for unconditional surrender. The German high command then ordered the sailors to make a last-ditch effort in the North Sea. But knowing this would be a suicide mission and influenced by movements such as Liebknecht’s Spartacists, the sailors mutinied.

In the Reichstag on November 9, Social Democrat Philipp Scheidemann declared Germany a republic and Kaiser Wilhelm abdicated and fled to the Netherlands. Shortly after, Liebknecht stood before a crowd at the Berlin City Palace to, somewhat prematurely, declare the formation of a Free Socialist Republic.

But on November 10, the Workers and Soldiers Council of Berlin threw its support behind new chancellor Friedrich Ebert.

Ebert became head of a Council of People’s Commissars, comprised of socialist groups who were opposed to all-out revolution. Liebknecht tried to complete the revolution but the signing of the Armistice on November 11 took the wind out of the sails of his movement.

Despite the setback, he and other Left-wing socialists maintained popular support. On December 19 Ebert announced that elections for a new constituent assembly would be held in January. But on December 23 revolutionary socialist sailors occupied the Chancellery and took Ebert into custody.

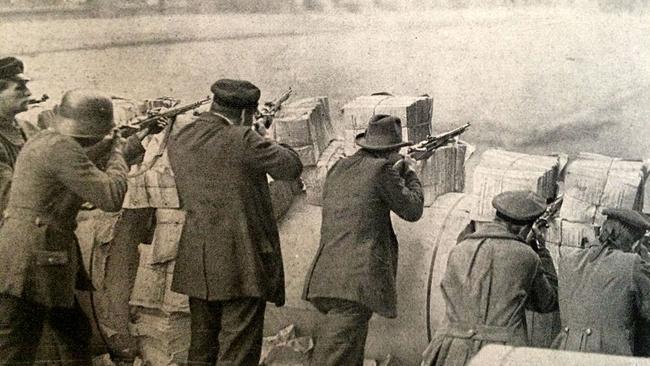

However, when Ebert was liberated by soldiers he began organising a militia, mostly from returned servicemen, to take care of his political opponents. It became known as the Freikorps.

On January 4, 1919, the dismissal of independent socialist Robert Emil Eichhorn sparked a wave of protests and a general strike, which became known as the Spartacist Uprising. But Ebert successfully deployed the Freikorps to take control. By January 13 the uprising was over.

Liebknecht and Luxembourg were both captured, interrogated, tortured and summarily executed on January 15. It marked the end of the German revolution.