First US POW was captured from a malfunctioning midget sub

The Japanese midget submarines sent in to attack Pearl Harbor didn’t live up to expectations and then provided the US with their first prisoner of war in WWII

While Japanese planes rained fire on the US fleet in Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, a smaller, more clandestine operation was unfolding beneath the surface.

The Japanese had also sent in five midget submarines — two-man, battery powered vessels equipped with torpedoes. Because they were so small they had a devastating potential to sneak deep into the harbour and unleash further damage.

However, that potential was not fully realised by the Japanese, who didn’t know how to use the subs to their full effect. During the attack the sub crews reported successfully attacking ships, but there is no evidence any of them dealt a fatal blow. Four subs ended up on the sea floor and the fifth had problems with its gyroscope and eventually struck a reef.

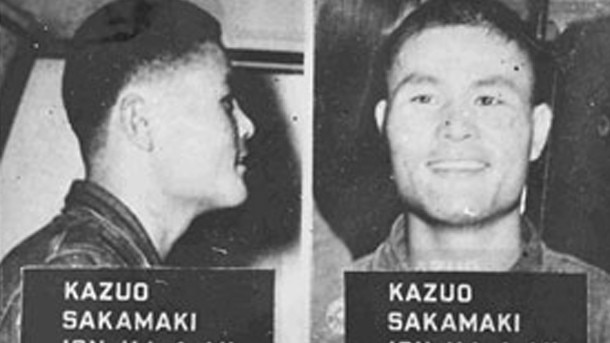

Its crew were knocked unconscious by a shot from a US destroyer but eventually came to. Ensign Kazuo Sakamaki tried, but failed, to scuttle the sub by lighting a self-destruct fuse. Instead he and his crewmate, Kiyoshi Inagaki, dived into the water to make for shore.

While Inagaki drowned, Sakamaki drifted unconscious to the beach, where he became the first Japanese person taken prisoner-of-war by the US.

It was the end of Sakamaki’s war but he would find fame, mixed with shame and infamy, as POW number one.

MORE FROM TROY LENNON

War play helped exorcise solder’s demons

Sakamaki was born on November 8, 1918, a century ago today, in the city of Awa, on the island of Shikoku. He later claimed his birth date was November 18, after World War I had finished, which gave him his name Kazuo — meaning peace boy.

Awa was a small village on Japan’s smallest and most sparsely populated island and Sakamaki said he had a happy childhood there. His father was a schoolteacher and Sakamaki intended following in his father’s footsteps but while still at school he saw soldiers heading off to fight the Chinese and decided he wanted to join the military.

In 1937 he successfully applied to the Japanese Naval Academy, beating thousands of other applicants from all over Japan to become one of a select 300 students.

Cadets at the academy were subjected to gruelling physical training and had to maintain a high academic standard. Complete obedience was also drummed into them and they were told that it was a great honour to die on the battlefield. Sakamaki graduated from the academy in 1940, and was commissioned a midshipman, serving on a cruiser in the war against China.

Promoted to ensign in April 1941 he was selected for a secret mission, to be part of the crew of a midget submarine spearheading the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. His selection was based on the fact that he was one of eight children in his family.

Sakamaki underwent intensive training before being unleashed at Pearl Harbor.

But the training proved useless during the actual attack as the sub malfunctioned and became stuck after striking the coral reef. It was dislodged by the shot from USS Helm which knocked Sakamaki and his comrade unconscious. They woke up to find the sub drifting helplessly, and after their failed attempt to scuttle the sub, abandoned ship.

When Sakamaki regained consciousness on the beach at Pearl Harbor he was confronted by a gun pointed at him by American sergeant David Akui, who took him prisoner. It was a moment of great shame for Sakamaki who would have preferred to have been shot or at least had time to kill himself. Instead he was taken away to be interrogated before being locked in a Hawaiian prison.

His repeated requests to be allowed to take his own life were denied.

While his midget sub toured the US helping to sell war bonds, in February 1942 Sakamaki went on his own US tour to the mainland where he was held alongside Japanese civilians in Wisconsin. The kindness offered by the American captors changed his attitude toward suicide and made him question the strict military codes he lived by. He spent time in four different camps in the US often counselling other Japanese POWs about accepting captivity and not killing themselves.

At war’s end he went home to Japan, where his fame preceded him and he received letters from admirers, many of them single women looking for a husband. In 1946 he married a woman he met after seeing her working in a neighbour’s field. He found employment with Toyota, becoming president of the company’s Brazilian subsidiary in 1969.

In 1991 he was invited to the US where he was reunited with the submarine he had piloted in the war. He died in 1999 survived by his wife and two children.