Faraday school kidnapping: How a schoolteacher in long boots foiled $1m ransom plot

IT was crazy enough the first time an ambitious but bumbling criminal kidnapped an entire Victorian school at gunpoint, only to be foiled by a teacher and her knee-high boots. But then he went back and did it again.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MAJOR crimes can reveal the best and worst in people. Victoria’s Faraday kidnapping in 1972 is a great example.

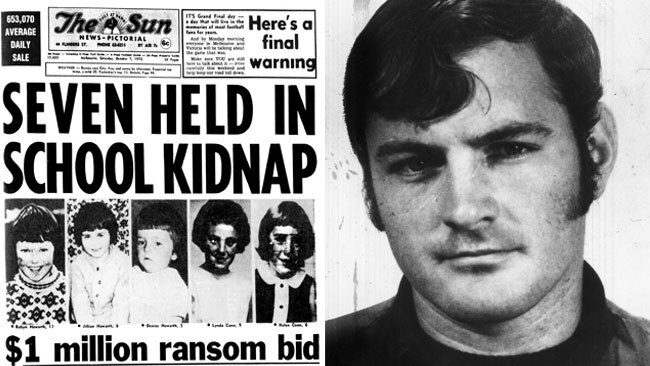

Callous greed led masked kidnappers Edwin John Eastwood and Robert Clyde Boland snatched six little girls and their 20-year-old teacher from the one-room Faraday Primary School on October 6, 1972.

One of the men stood in the doorway, armed with a rifle.

He smiled and said: “There’s no more school today, kids”, before herding them out of the one-room school.

Another four children were away sick that day.

Panic set in when parents came to pick up their children from the little granite school building, 120km northwest of Melbourne, and found it deserted.

Miss Gibbs’ Holden Torana was still parked out the front.

About 4.40pm, The Sun’s chief crime reporter, Wayne Grant, took a call from one of the kidnappers.

“I’ll say this only once,” the caller told Grant.

“I’ve kidnapped all the pupils and the teacher of the Faraday State School.

“The ransom is $1 million. Look for a note in one of the front desks.”

The caller hung up.

After checking with police, Grant and colleague Joe Rollo raced to the scene.

The note demanded $1 million for the safe return of Miss Gibbs and the children — $500,000 in $20 notes in three suitcases and the rest in $10 notes, in six suitcases, with all notes to be in circulation for at least a year.

‘At 7.25pm we will contact Lindsay Thompson at Russell St police headquarters and make arrangements with him’, the chilling note read.

“We are not going to waste anyone’s time by making idle threats, so we will cut it short by saying that any attempt to trace us or apprehend us will result in the annihilation of every hostage.”

iTUNES: SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES WITH ANDREW RULE PODCAST

ANDROID: SUBSCRIBE TO THE LIFE & CRIMES WITH ANDREW RULE PODCAST

Eastwood, then 22, and Boland, 32, drove their captives southeast to an isolated bush track near Lancefield, where they had hidden a car.

Mr Thompson was at home when police Assistant Commissioner (Operations) Mick Miller phoned him about 5.30pm.

“To be truthful, at first I thought it was a crank call,” Mr Thompson told Rollo in The Sun in 1989.

“I didn’t know Miller and told my wife that someone had phoned about a one-teacher school being kidnapped.”

Miller instructed him to come to D24 in Russell Street to await a call to him from the kidnappers at 7.25pm.

The call came, but never got through the switchboard to Mr Thompson.

Unaware, Mr Thompson and Premier Rupert Hamer, also at D24, decided to get the ransom ready.

The caller tried again at 3am on Saturday, demanding Mr Thompson bring the $1 million to the Woodend post office, on the Calder Highway about 65km northwest of Melbourne, at 5am.

No one knew if the call was a hoax urged on by the breaking news of the kidnapping, but Mr Thompson was mobilised.

Miller asked if he’d be willing to deliver the ransom, and he agreed.

An unmarked police car picked up Mr Thompson, with Miller, Assistant Commissioner (Crime) Bill Crowley in the back seat and a detective, Bill Kneebone, posing as a driver.

Miller and Crowley, armed and ready to pounce, laid out of sight: Miller under a blanket on the floor in the back, and Crowley across the front seat, with the car door opened slightly.

Other police were stationed nearby.

At 5am, in the pre-dawn chill, Mr Thompson waited in a suit and an overcoat and a satchel containing $1 million under his arm, waiting for the kidnappers to come for the ransom.

“The quiet was almost unnerving and the pre-dawn darkness made it all quite eerie,” he told Rollo in 1989.

“Not quite sure what to expect, I kept going through a plan of action, in case the kidnappers tried to grab me.

“I felt like the loneliest man in the world.”

Three minutes later, an old Holden ute appeared in the desolate main street.

“He drove up a short way, turned and drove back. Still slow, still staring directly at me,” Mr Thompson said.

It disappeared for a moment, then returned.

The driver parked and a young man walked towards Mr Thompson, who was bracing for the worst, and blurted out: “What in the hell do you think you’re doing wandering around here at 5 in the morning!”.

The startled man said he was looking for a mate he’d lost while the pair was drinking.

Police grabbed the innocent timber worker nearby and Mr Thompson’s anxious wait resumed.

As dawn broke, they decided to leave, driving by Faraday before returning to Melbourne.

They needn’t have worried.

As they arrived in Woodend, about 20 minutes away Miss Gibbs used her high, platform-soled leather boots to smash out a panel in the back door of the van and free the girls.

As the teacher walked the girls out of the bush, they were found about 8am by rabbit hunters who took them to the one-member Lancefield police station.

The kidnappers had earlier told Miss Gibbs they were heading out to collect the ransom when they’d abandoned them in the van.

But during the night they lost their nerve, fearing a trap.

“When they didn’t come back before dawn, I thought it is now or never and began kicking at the door,” Ms Gibbs told The Sun at the time.

“I don’t think we could have got out without the boots.”

She and the eldest girls — Robyn Howarth, 11, and Christine Ellery, 10 — took turns at kicking the doors.

Then, with Christine holding a small chain attached to the van wall, Miss Gibbs leaned on the girl’s shoulder and kicked repeatedly.

“God knows how many times, but then, bit by bit, things started to give,” she said.

“It was fantastic. I crawled out and the girls followed.

“I was petrified the men would come back and catch us.”

Robyn Howarth said she feared for her life.

“I was scared they were going to kill us for nothing,” she said.

“They said they had nothing to gain from killing us — and nothing to lose either.”

In 1973, Miss Gibbs was awarded the George Cross for her bravery.

The Faraday school never reopened, and was sold by the government in the mid-1990s.

Police closed in on the kidnappers by the following Monday.

At 4.10am, Eastwood was arrested at a house in Edithvale.

Twenty minutes later, police raided Boland’s Bendigo home.

Both had minor criminal records before the kidnapping.

Eastwood and Boland were sentenced to 15 and 16 years respectively.

Eastwood confessed to the crime but said Boland, who pleaded not guilty, was not his co-conspirator.

On December 16, 1976, Eastwood broke out of the Geelong Training Prison.

Then, on February 14, 1977, he kidnapped a teacher and nine children from the tiny Wooreen Primary School in South Gippsland, who were aboard a school bus, later also kidnapping six other adults.

Teacher Robert Hunter had been in his first teaching job a matter of days.

Eastwood demanded the release of several criminals, including Boland, $7 million cash and 100kg of cocaine and heroin before he was wounded in the knee in a shootout with police.

Mr Thompson, still Education Minister, had offered himself to Eastwood in exchange for the hostages.

After his arrest, Eastwood told police: “I’m getting better each time, and I will get it right eventually”.

Prison authorities foiled a second escape bid by Eastwood in 1979.

He was acquitted on the grounds of self-defence of the 1980 strangling of fellow inmate Glen Davies inside Pentridge.

Boland was released in 1983.

Eastwood embraced the Seventh Day Adventist Church in 1981 and was baptised in jail in 1985.

He was eventually released in 1993, changed his name by deed poll to David Jones and wrote a book about the Faraday kidnapping, Focus on Faraday and Beyond: Australia’s Crime of the Century — The Inside Story.

Originally published as Faraday school kidnapping: How a schoolteacher in long boots foiled $1m ransom plot