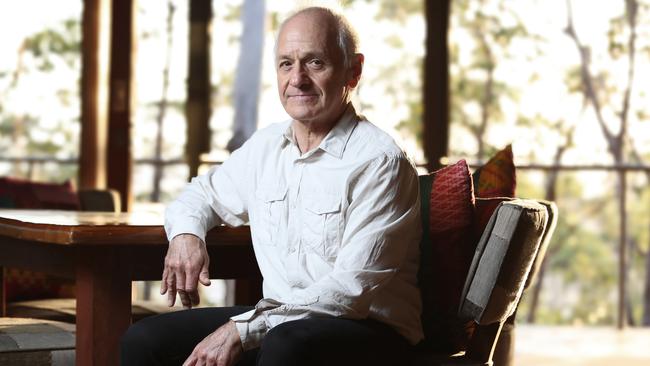

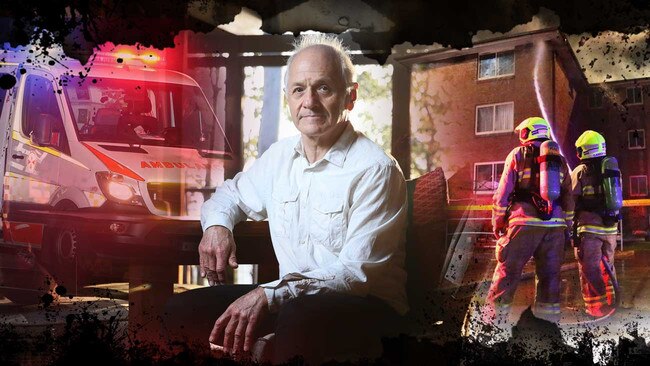

Clinical psychologist Stephen Heydt has spent 40 years working on the mental health of Australian police, paramedics and firefighters. He offers a unique insight into the minds of our everyday heroes who have to deal with immense trauma daily.

Stephen Heydt has seen first-hand the worst of what humankind can be forced to endure.

First as a soldier conscripted into the South African Army before fighting Namibia and then later as a civilian worker in war-torn Afghanistan helping demobilise Mujahideen.

But it is in his almost 40-year career as a psychologist with the NSW Police Force that he has realised frontline emergency responders are exposed to the “slop drip of trauma”’ not experienced by soldiers.

“I’m not sure that the human brain is designed to deal with this day in, day out, week in week out,” Mr Heydt told The Night Watch.

“For most military personnel, they would encounter a single incident in the course of their career. For first responders it is this incessant, every day (potential) of ‘I’m going to be seeing someone in a horrible situation’.

“Their bodies and their brains start prepping for it every day – I get referrals from GPs all the time and they always state that people have got elevated blood pressure and heart rates.”

LISTEN: Clinical psychologist Stephen Heydt has worked with an array of first responders and emergency services workers across NSW, Victoria, Queensland as well as with the Australian Federal Police. He offered The Night Watch a unique insight into the mind of an everyday hero.

After finishing his conscription, Mr Heydt studied economics and accounting “which was probably not the best choice” before switching to psychology.

A move to Australia in the early 1980s led him to the NSW Police Force and its homicide squad. He has spent the 40 years working on the mental health of Australian police, paramedics and firefighters.

“Most of my clients haven’t necessarily been injured in the course of their experiences, particularly in the emergency services in a physical sense,” Mr Heydt said.

“And I have this view that a physical injury is perhaps easier to deal with in that it’s more obvious and you’re more inclined to get obvious support and more immediate support.

“I think one of the difficulties is that many of the first responders suffer with mental injuries for a very long time, and it’s almost as if they are re-injured a number of times.

“And most that I see would have suffered chronic trauma repeated and repeated and repeated incidents which have resulted in them over long periods of time deteriorating until some has perhaps tapped him on the shoulders and said ‘you’re looking terrible’, or perhaps they’ve literally been unable to continue working.”

Now based in private practice in the hills overlooking Brisbane, Mr Heydt argues going to traumatic jobs changes the way first responders function.

“They come to anticipate events on a regular basis – I am of the view that they come to live with a higher heart rate, a higher level of underlying anxiety,” he said.

“There is this incessant, this slow drip of incidents that eventually do fill the glass or the bucket.

“I’m not sure that even in primitive times and where there were warring villages that we encountered as much regular mental trauma as police are being subjected to.”

Heydt has also seen trauma while at work himself.

In 2002, he worked in conflict resolution with the Mujahideen in Afghanistan, training former jihadis to clear landmines.

During the job he saw gruesome injuries after landmines had exploded.

He said we need to take greater care of our first responders.

“We’re throwing them into conflict almost on a daily basis and it’s egregious conflict, it’s conflict involving loss of life and limb – quite literally – I don’t think we’ve given enough attention (to this),” he said.

“I can’t recall the last police officer I’ve met who’s taken time off after a critical incident other than when they’ve completely fallen over and been unable to return to work.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout