Cubans rose up against Spain in first war for independence

WHEN a Cuban plantation owner plotted rebellion against Spain he was forced to move it forward four days

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

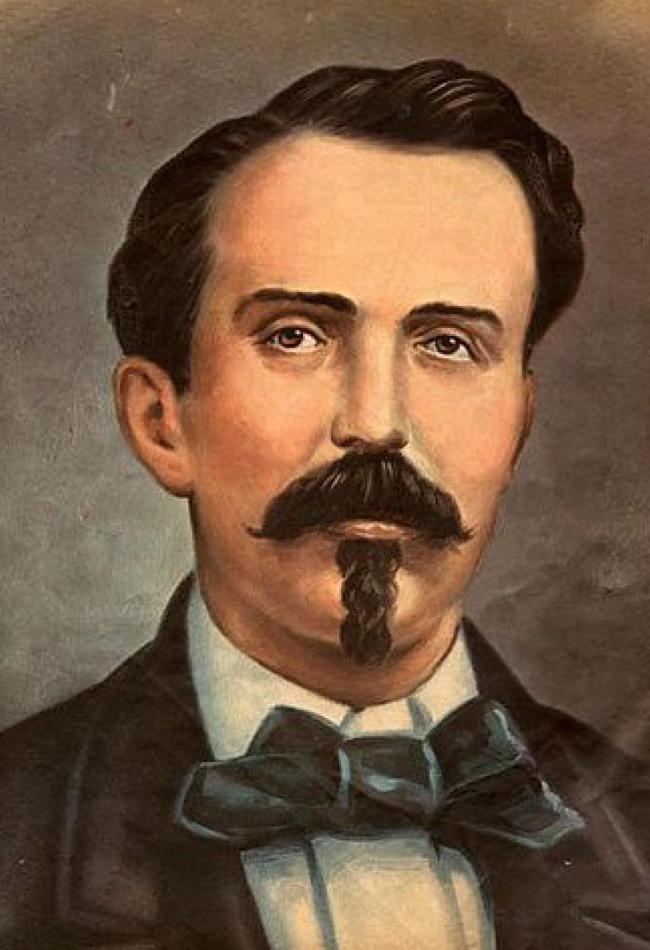

WHEN Cuban plantation owner and lawyer Carlos Manuel de Cespedes began planning a rebellion against the Spanish he set down the date for October 14. Unfortunately for him the Spanish got wind of the revolt so, in order to get back the element of surprise, Cespedes had to change the day, moving it forward to October 10, 150 years ago today.

As that day dawned, he rang the bell normally used to summon his slaves. Cespedes and 147 followers gathered at his sugar plantation and mill, La Demajagua, near the town of Yara, where he gave an impassioned speech declaring this to be the first day of Cuba’s independence from Spain and promising the gradual abolition of slavery in Cuba. It would be known forever as El Grito de Yara, the cry of Yara.

He issued a manifesto of complaints against Spain and broadly outlined their aspirations including popular sovereignty, universal suffrage, equality and freedom from the “yoke of Spain”. Inspired by his words, the rebels armed themselves with whatever weapons they could to prepare to confront the Spanish garrison forces.

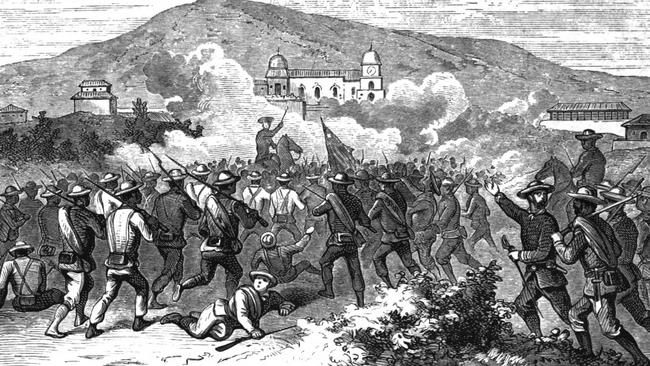

Other planters soon threw in their lot with Cespedes, freeing their slaves and encouraging them to fight. The first shots in the rebellion were fired during the attack on Yara on October 11. However, the rebellion almost faltered at its first hurdle. Eventually Cespedes and his men prevailed, capturing the town. More victories followed and by the end of October, more than 12,000 Cubans had joined the rebellion.

For 10 years the Cubans would wage war for their independence before Spain finally forced the revolutionaries into submission. But Cuba’s Ten Years War, as it became known, lit the spark for future battles.

In the 1860s dissent against their Spanish overlords was growing in Cuba. Only around 10 per cent of the population were “peninsulares” Spanish-born citizens, but they owned 80 per cent of the wealth. The citizens who had been born in Cuba or whose families had lived there for generations, known as criollos, resented Spanish control, taxation, the presence of repressive military forces and the persistence of slavery.

Slaves were no longer necessary, they took jobs from locals and had actually become more expensive to maintain than free workers.

As protests grew louder and more frequent the Spanish response was repression: banning reformist meetings and increasing taxes. But the repression only strengthened the resolve of men like Francisco Vicente Aguilera, a rich landowner who, in July 1867, formed the Revolutionary Committee of Bayamo.

He also offered to give away all of his wealth to fund a Cuban revolutionary army, knowing that Spanish intransigence might soon lead to violence as the only course of action.

Other cities also formed revolutionary committees, pledging to act together when the time was right. Cespedes joined the movement soon after. He had studied law in Spain but had been deported for his involvement in the 1843 revolution. He therefore had practical experience of insurrection. Cespedes spent time in exile in France before returning to Cuba to join the ranks of dissidents. After joining Aguilera’s movement he soon rose to become one of its leaders.

In September 1868 revolution broke out in Spain and the Cubans saw their opportunity. Cespedes began to plot the overthrow of Cuba’s Spanish overlords. On October 10 he made his speech, issued his manifesto and the next day led rebels into battle.

Heartened by a series of victories the Cubans formed their own government in April 1869, electing Cespedes as president. A new constitution was introduced abolishing slavery, but Cespedes had expressed reservations about immediately freeing the slaves.

Meanwhile, Spain poured troops into Cuba to quash the rebellion. As things began to go badly and opposition to Cespedes mounted, he was deposed in 1873 and went into hiding. In 1874 he was killed by Spanish soldiers.

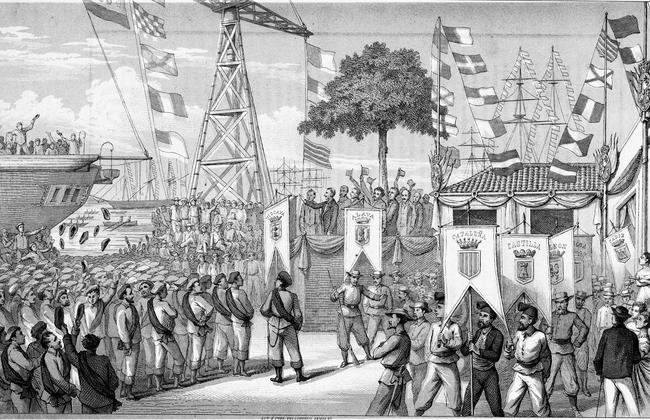

By 1878 the Spanish were in a stronger position and the rebels entered negotiations for peace. Some concessions were given but Cuba lost its independence — for the time being. Another uprising in 1879 also ended in defeat in 1880.

But there was hope. Among the rebels who had fought the Spanish, but was caught, imprisoned and exiled to Spain was 18-year-old student Jose Marti. He would spend years planning revolution with other Cuban exiles, raising funds in America before taking part in the 1895 uprising. With help from the US Cuba won its independence from Spain in 1898 but was occupied for a time by the US.