Chicago doctor Dr Daniel Williams’ first heart surgery patient lived another 20 years

CHICAGO surgeon Daniel Hale Williams stitched up a heart tear to save stab victim James Cornish 125 years ago.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THE gut was one thing, but abdominal surgery pioneer Theodor Billroth baulked

at attempts to operate on the heart.

Contemporaries at a Vienna Medical Society meeting reportedly heard him mutter in 1881: “No surgeon who wished to preserve the respect of his colleagues would ever attempt to suture a wound of the heart.”

A year later German surgeons reported it was possible to suture heart wounds in animals, and 125 years ago, on July 10, 1893, Chicago surgeon Daniel Hale Williams performed a similar operation on stab victim James Cornish, 24.

Although listed as the first documented, successful pericardium surgery in the US to repair a heart wound, St Louis City Hospital superintendent and surgeon Henry Dalton reported performing a similar procedure on a 22-year-old stab victim on September 6, 1891.

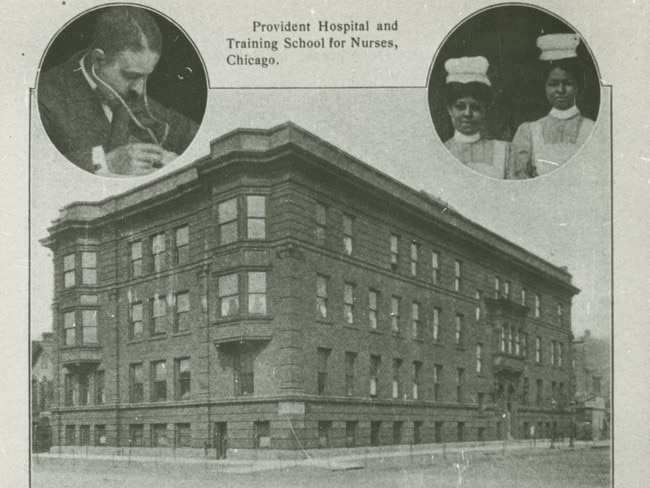

Williams had already earned a place in medical history in 1891 when he founded Provident Hospital, the first non-segregated hospital in the US, and an associated nursing school for African American students.

Williams was born on January 18, 1856, at Hollidaysburg, Pennsylvania. His father was the son of a black barber and a Scots-Irish woman; his mother Sarah was also African American, and likely of mixed race. Their fifth child, Williams had one brother and five sisters. His family had moved to Annapolis, Maryland, when his father died of tuberculosis in 1865. Sarah moved the family to live with relatives at Baltimore, where Williams was apprenticed to a shoemaker. By age 17 he had also studied and become a successful barber, living with a family in Janesville, Wisconsin, where he worked in their barber shop. He also attended high school and later an academy, graduating at age 21. He began medical studies as one of three apprentices with surgeon Henry Palmer and in 1880 was accepted for a three-year program at Chicago Medical School, then affiliated with Northwestern University. In 1883 he graduated with a medical degree and began a practice in Chicago, which had just three black physicians.

Williams also took an appointment at South Side Dispensary, to practice medicine and surgery, and was appointed to the City Railway Company and Protestant Orphan Asylum. He treated black and white patients in his practice, but was aware of limited opportunities for black physicians. Appointed to the Illinois State Board of Health in 1889, as he worked with medical standards and hospital rules he noted prejudice against, and inferior treatment often given to, black hospital patients. He was also approached by church pastor Louis Reynolds, whose sister Emma wanted to be a nurse but was denied admission by all Chicago nursing schools because she was black.

Unable to convince existing schools to accept Emma, Williams and Reynolds decided to open a nursing school for black women. They then consulted black ministers, physicians and businessmen to explore opening a nurse-training facility and a hospital.

Chicago’s black physicians had limited or no hospital privileges, and community leaders assured support. Rallies were scheduled on Chicago’s south and west sides to raise donations of supplies, equipment and financial support. Clergyman Jenkins Jones secured a commitment from Armour Meat Packing Company in 1890 to cover a down payment on a three-storey brick house in the city’s south, where the first Provident Hospital opened with 12 beds in 1891.

Cornish, an African-American delivery worker, was drinking scotch and playing cards on a hot night in a south Chicago bar when a fight engulfed him. Stabbed in the chest, he was taken to the Provident Hospital late on July 9, 1893.

Stabbed directly through the left fifth costal cartilage, Cornish had a fading heart beat and “pronounced” symptoms of shock when Williams decided to operate next morning. Without X-ray images, antibiotics, blood transfusions or modern anaesthetics, Williams cut a small hole in Cornish’s chest. He worked past nerves, muscle, blood vessels and ribs to reach Cornish’s heart, beating at about 130 times a minute. Williams found a severed artery which he stitched closed, then noticed an inch-long gash in the pericardium, the sac around the heart. Williams sutured the pericardium tear with catgut, and noted that Cornish’s heart had been nicked, but did not need sutures. Cornish was discharged 51 days later, to live another 20-odd years.

Williams continued a surgical and academic career until his death in 1931.