Captured Lives: New book probes life on wartime Torrens Island

WHEN Australia found itself at war, thousands of people were deemed security threats. They soon found themselves dwelling under brutal conditions in the swamp that was Torrens Island.

National

Don't miss out on the headlines from National. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SECRET camps housing thousands of inmates, many convicted of no crimes, and some of them flogged and shot – if it happened nowadays there would be a national uproar.

But in 1914, as the Great War began, Australia discovered it had “enemy aliens” in its midst. The nation, and South Australia in particular, were to go through a steep learning curve for how to deal with them.

In two world wars over the coming decades, many thousands of internees would be held in SA, many would be treated disgracefully, and some were even assassinated.

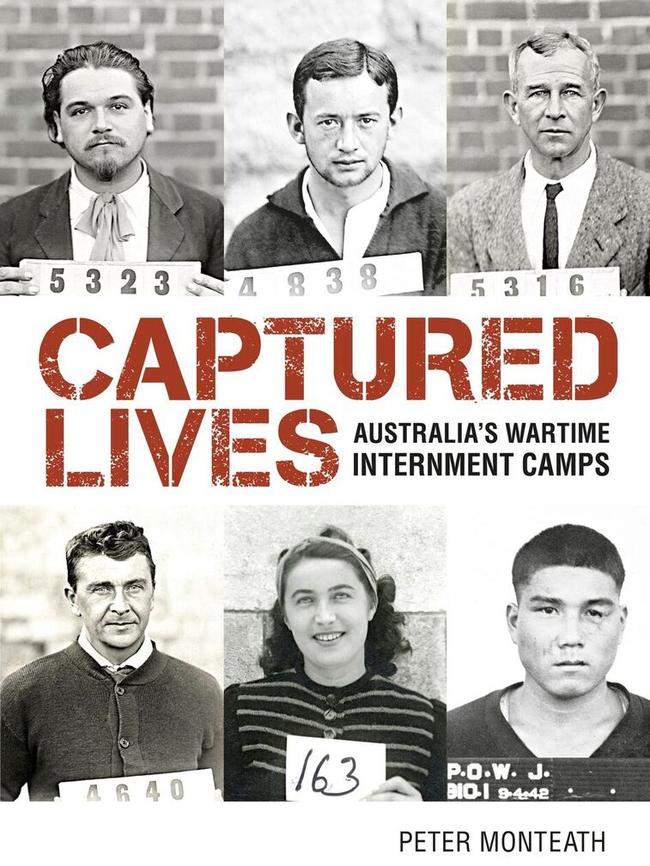

Many SA families have members who were interned and the remarkable history of the wartime camps is catalogued in a new book Captured Lives, by Flinders University history professor Peter Monteath.

Prof Monteath says the history of internment during the wars in the state saw many injustices committed, including putting those in prison for simply having the wrong surname.

“Lots of those interned would have considered why they were there,” he says.

“You wonder about the motives of those that voiced suspicions of others.

“It could have been they had a personal vendetta against someone or be a business rival and this was an opportunity on very little evidence to see them suffer.”

Other reasons for why someone was interned were more straight forward.

“If you were a young man and a reservist who had done his training in Germany then Australia couldn’t risk you heading back home and serving with the enemy,” Prof Monteath says.

Those opening days and months of World War I were particularly difficult for South Australians because of our large well-established German population.

Many of German descent had been in SA since European settlement, and many towns and places had names from the nation.

Germans were continuing to arrive and be naturalised in what appeared to be a welcoming community. So no one knew quite how to react.

The German vessel SS Scharzfels steamed up Gulf St Vincent on August 5, 1914, the day after Prime Minister Andrew Fisher, declared Australia would support Great Britain “to the last man and the last shilling”.

A customs vessel came out of Port Adelaide and gave Captain August Strycker the news the two countries were at war.

He was told that he, his crew, his vessel and his cargo were now under Australian control.

The German crew members were put on parole and moved into a house in Port Adelaide.

Within days Australian authorities were told to arrest and detain Germans who had military training and might be called up to serve.

Soon, as war escalated, SA authorities – free to interpret which enemy subjects showed “suspicious or unsatisfactory” conduct – took firmer action.

While few Australian-born Germans would be interned, there were many naturalised Germans and Austro-Hungarians (and small numbers of Bulgarians and Turks) in Australia and these people would have a tough time during the next few years.

By October 1914, it had been decided to open an internment camp on Torrens Island, a camp that would gain the worst reputation of all Australia’s internment camps.

People were rounded up by the hundred and brought to Torrens Island. Lives changed dramatically.

A German tourist and photographer visiting Adelaide, Paul Dubotzki, went from staying at the up-market South Australian Hotel on North Tce to a makeshift tent on Torrens Island.

The first camp was on a mosquito-ridden swamp subject to flooding in high tides. The internees raided the rest of the island in search of timber to help make their improvised eight-man tents more liveable.

A new commandant of the Torrens Island camp, Captain George E. Hawkes, a 37-year-old bank teller from Glenelg, instituted brutal treatment of the internees.

It reached a crisis when he ordered the cat o’ nine tails flogging of two escapees.

A military inquiry followed, where Captain Hawkes was exonerated.

However, an independent investigation by the US consul-general uncovered a litany of cruel treatments at the camp, documented by Dubotzki’s photographs.

Prof Monteath says there were shameful acts committed in SA internment camps, with the worst violations happening under the regime of Hawkes at Torrens Island.

“On his watch, guards used bayonets on prisoners and a prisoner was shot and injured but it happened out of the public eye,” he says

“At the time, these were secret facilities people were not supposed to know anything about. No one had much of an interest shining a light on things then – or since.

“There are connections with what happened at the time of wars with what happened in Australia before then and even in the present day because we’re still putting away people on islands.”

In World War II, an entirely new concentration camp was created in SA, this time at Loveday, near Barmera, on the River Murray. It was to be the largest civilian internment camp complex in Australia.

Authorities intended to keep numbers below that of the World War I but then Italy and Japan entered the conflict and that swelled numbers in the camps.

Loveday was actually a series of camps, the first housing Italians from all parts of Australia, the next for Germans, and another for Japanese, who were generally interned with their entire families.

By 1943, Loveday was home to 5382 internees.

The availability of water for irrigation meant that many raised market gardens and orchards. When the authorities decided to keep internees active by paying for their labour, it included growing poppies for morphine for civilian and military use.

In 1944, Loveday produced half the morphine required by the Australian military forces that year.

With people of all political persuasions, Germans who were ardent Nazis, fascist Italians, and a political spectrum ranging to Italian anarchists, tensions ran high.

Italian anarchist Francesco Fantin was found dead, battered by a tap stand. Giovanni Casotti, a fascist, was sentenced to two years for manslaughter.

As Allied victories gained momentum, internees were released from Loveday.

The Italians were first, many of them being released, with conditions, after the Italian Armistice in September 1943.

Most of the Germans were held until the end of the European war, while of the 2200 Japanese, subject to particular vilification, nearly all stayed at Loveday until the end of the Pacific War. By mid-1946, long after the war, there were still internees at Loveday.

The Geneva Convention meant those who were not natural-born Australians or naturalised were to be repatriated, and that involved long delays, with people often reluctant to be leaving Australia.

They were told they could reapply in the normal way once they had returned home.

Captured Lives, (Quikmark Media $39.99). Professor Monteath will be part of a discussion of the Loveday internment camp hosted by the Migration Museum in the city, on October 3 from 6pm. Bookings through Eventbrit.

Originally published as Captured Lives: New book probes life on wartime Torrens Island