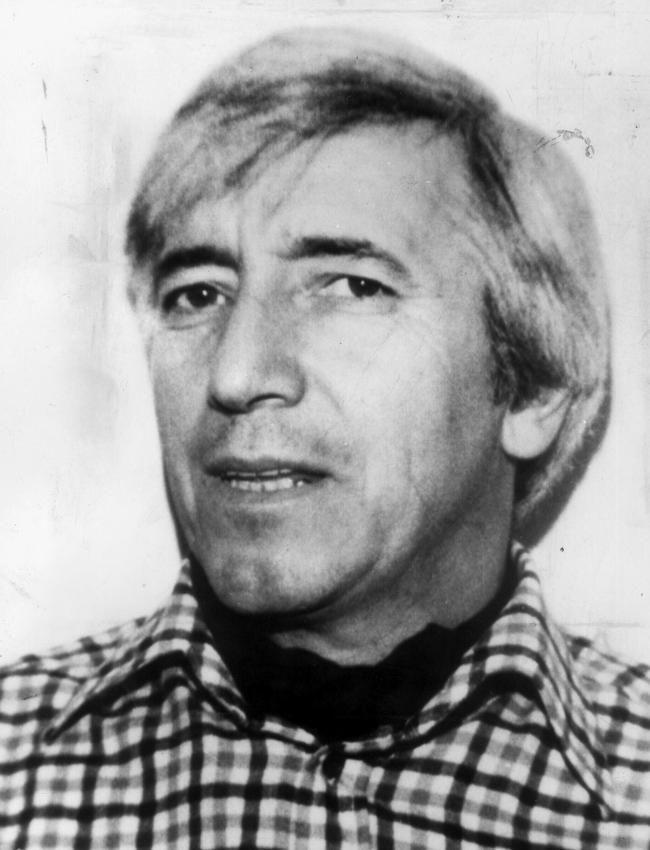

Bulgarian dissident Georgi Markov ‘shot’ by killer poison pellet from an umbrella

BULGARIAN defector Georgi Markov felt a sting in his leg while waiting at a bus stop in London, he died a few days later, forty years ago today

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

AS Georgi Markov stood waiting at a bus stop near Waterloo Bridge in London on September 7, 1978, he felt a sudden stinging pain in the back of his thigh. He turned expecting to see someone who might apologise for poking him, but only saw a man hastily picking up a dropped umbrella, who then rushed across the road to jump into a taxi.

As a Bulgarian dissident who feared the reach of communist agents, Markov had reason to be suspicious. Yet he continued on his way to work at the BBC in Bush House, thinking little of the encounter. But the pain in his leg refused to go away and a small lump began to form. By the evening he had developed a fever and was rushed to hospital. But the doctors didn’t realise there was nothing they could do.

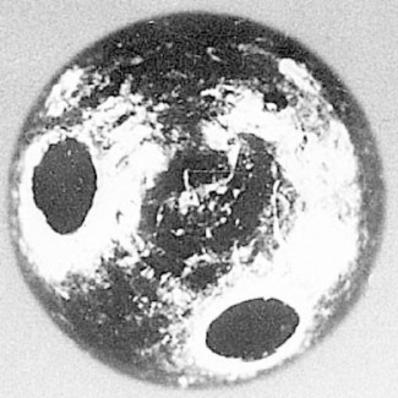

The man at the bus stop was armed with an umbrella that fired a tiny metal pellet containing a poison for which there was no antidote. Markov died four days later on September 11, 1978, 40 years ago today.

Initially thought to be blood poisoning from the wound in his leg, an autopsy revealed a pellet made of platinum and iridium embedded in his thigh. It had two holes drilled in it containing the poison. These were coated with something designed to “melt” once it entered the body. Experts believed the poison was ricin.

It was like something out of a spy film — a man being killed by a gadget containing a mysterious poison. Markov’s death, during the Cold War, showed the lengths that communist governments would go to silence people who spoke out against them.

The recent poisonings of Russian dissident Sergei Skripal and his daughter Yulia have been likened to Markov’s death and show that some east European governments are still capable of clandestine murder.

Born in Knyazhevo, a semirural suburb on the outskirts of Sofia, Bulgaria, on March 1, 1929, Markov’s father Ivan was a career officer in the Bulgarian army who was invalided out in 1943 because he suffered from tuberculosis. After the war Ivan worked in the tobacco trade.

Georgi Markov wanted to study literature but failed to gain entry to Sofia University. So, at the urging of his father, he undertook training as a chemical engineer. Through the 1950s he worked as an engineer at various factories around Bulgaria before ending up in Sofia teaching at the Ceramic Technical School.

In the early ’50s, he also was diagnosed with tuberculosis, which he had contracted while working in a brick factory in his youth. While being treated for the disease and convalescing, he wrote stories and in 1957 published a collection of science fiction short stories titled Tsezieva nosht (Caesium Night). Encouraged by the book’s success, in 1959 gave up teaching to devote himself full time to writing.

His next work was another collection of science fiction but in the ’60s he turned to other forms of literature, examining the everyday lives of Bulgaria’s citizens — considered a more “serious” form of literature. His breakthrough work was his first full-length novel Muzhe (Men), published in 1962, about three young members of an army unit and their different passages to manhood. It was praised by the leading literary journal of the day and saw him invited to be a part of the literary establishment.

He was even taken into the inner circle of Bulgarian communist leader Todor Zhivkov, who hoped to harness Markov’s skills to write works supporting his rule. But Markov wouldn’t allow his works to be bent toward propaganda. By the end of the ’60s he was frustrated by censorship of his novels, plays and other writings. One of his plays was even denounced as a “Czech play” — a reference to the anti-Soviet uprising in Prague in 1968.

In 1969 he left Bulgaria for Italy, realising that the authorities were closing in and leaving behind wife Zdravka Lekova. In 1971 he moved to London finding work with the BBC’s Radio Liberty (later Radio Free Europe) which broadcast uncensored news and information to countries behind the Iron Curtain during the Cold War.

Freed from the strictures of his homeland, Markov was able to write whatever he wanted about Bulgaria and the communist government. But the Bulgarian and Soviet governments were closely monitoring his work for the BBC and others. He was declared an enemy of the people.

Markov reported receiving death threats and told people he feared for his life. Ten days before he was attacked at the bus stop a similar attempt was made on another Bulgarian émigré in the Paris Metro. But the coating on the pellet didn’t “melt” and he survived.

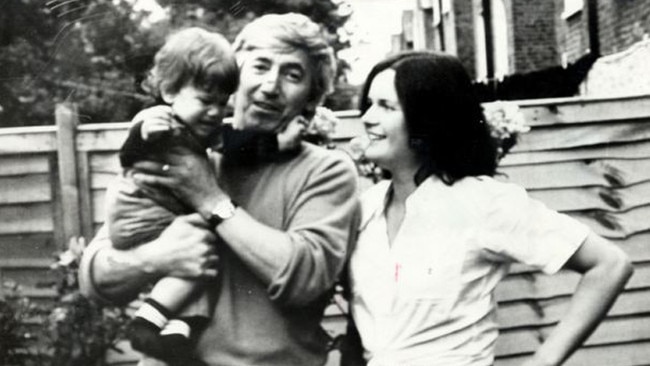

Markov was not so lucky. He was shot with the pellet on September 7 and died on September 11. He left behind second wife Annabel Dilke, whom he married in 1975, and daughter Alexandra-Raina.

It is still not known who the assassin was but there is little doubt it was the work of the Durzhavna Sigornost, the Bulgarian secret police.