SOUTH Australia is sometimes referred to as the crime capital of the nation.

And there’s no doubt many infamous crimes have occurred here — the Snowtown and Truro murders, the disappearance of the Beaumont children, the Somerton Man and the more recent deaths of the Rowe family, Carly Ryan, Anne Redman and Pirjo Kemppainen.

But there are thousands of other bizarre crimes across our state that haven’t received as much press coverage — especially those from our state’s earlier days.

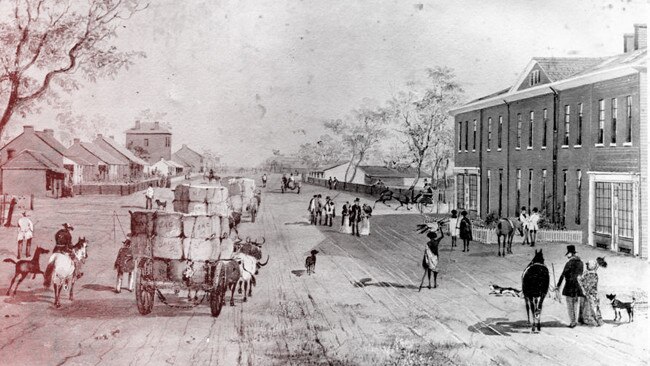

To mark the SA History Festival, here are some crimes dating back to the early 1800s that you’ve probably never heard of.

Who shot the Sheriff? — 1838

Michael Magee was the first person to be executed in South Australia on May 2, 1838.

But what crime was deemed so bad that it required our state’s first use of the death penalty?

Magee was tried and found guilty of shooting the Sheriff, Sam Smart, with intent to kill.

It was also believed that Magee was an escaped convict who had slipped into South Australia and found work on Kangaroo Island.

But until the day he died, Magee proclaimed he was a free man.

Once it was agreed that Magee should be hanged, authorities encountered a problem as there were no qualified hangmen in the colony.

Eventually, the cook at the South Australia Company was chosen for the duty and the location of the hanging was set — at the foot of a gumtree in North Adelaide.

As a crowd of about 500 gathered and the noose was placed around his neck, Magee admitted his guilt and told onlookers the sentence was justified.

In his book A Colonial Experience, Geoffrey Manning described the scene.

“As soon as the cap had been drawn over Magee’s face and the prayers concluded, a motion was made that all was ready,” he wrote.

“With a whip or two of the leading horse, the cart supporting Magee’s feet was drawn away, and many shut their eyes whilst the poor sufferer was launched into eternity.”

Unfortunately for Magee, what proceeded was a grisly execution.

A poorly-fitted noose and the hangman’s lack of experience led to a drawn-out conclusion to Magee’s life.

As he swung from the gum tree, the criminal was able to grab the rope around his neck and lift himself up.

Shouts of “cut him down” echoed from the crowd, but the hangman grabbed Magee’s legs and pulled down on them, ending his life.

As pockets of the crowd yelled angrily at the hangman, calling him a “murderer”, the South Australia Company cook was escorted from the scene by police.

It was actually the Sheriff himself — whose attempted murder instigated the fateful day — who finally quelled the tumultuous crowd.

Theft of a cooked goose on Christmas Day — 1845

Among the assaults and horse stealing of the early days of the colony, this case stands out.

William Williams, 37, a bricklayer’s labourer, was charged over the theft of a cooked goose on Christmas Day, 1845.

He allegedly stole the ready-to-eat meal — valued at 5 shillings — from Adelaide resident Alfred Cooper, a hairdresser, before taking it to a friend’s house to eat.

He came in, and saw his goose in the hands of the Philistines.

The South Australian newspaper reported that Cooper “came in, and saw his goose in the hands of the Philistines. He then got a policeman, who took Williams into custody”.

But, in a late Christmas present, Williams was found not guilty when he faced court over the charge in 1846.

Where did the glass birds’ eyes go? — 1845

On December 24, 1845, a 14-year-old boy named Alfred Brook was charged over a similarly bizarre crime.

Brook, an apprentice boot maker, was charged with the theft of glass birds’ eyes from his employer, George Faulker.

A report in the local newspaper said the court was told that Brook had picked the eyes up from the floor of his master’s shop and “given some of them to a little girl named Rebecca Jane” — perhaps his sweetheart — who had promised not to reveal who gave her the present.

Brook was found not guilty of the crime in early 1846.

The investigation revealed that Mr Faulker was not only a bootmaker but a bird “fancier” and stuffer as well.

Imagine — less than 10 years after the colony was established, there was already such a demand for bird stuffing that someone could make a living from it.

Many of the birds Mr Faulkner would have stuffed are likely to be either rare or extinct today.

What happens when you kill the Inspector of Police — 1862

If you kill someone powerful, then you expect the full force of the law to come down hard on you — especially when that person is the Inspector of Police.

And that’s exactly what happened to aggrieved ex-police officer John Seaver.

On February 4, 1862, Seaver saw his opportunity.

The Inspector of Police, Richard Pettinger, was attending an auction at Government House, where Seaver and his wife were working at the time.

Stalking Insp Pettinger with a pistol hidden under a black cloth, Seaver waited for the opportune moment for the killing.

That moment came when the inspector entered the lobby; Seaver raised his gun and shot him in the head at close range.

The killer was arrested outside Government House shortly after the incident, while his wife was also charged with being an accessory before the fact.

An inquest was conducted that same evening in a room at Government House, while the inspector’s body lay in an adjoining room, and was concluded the next day at the Gresham Hotel, which used to stand on the corner of King William St and North Tce.

A Supreme Court trial was held just a week later.

Seaver’s wife was found not guilty by the jury and acquitted.

But Seaver was not so lucky. He was found guilty, sentenced to death and hanged at Adelaide Gaol on March 11, 1862 — the 31st person to be executed in the South Australian colony.

‘But the gun went off accidentally’ — 1871

Murders and attempted murders have always had their place in South Australia’s criminal past.

But the tale of shoemaker Carl Jung stands apart for his retracted confession and simple defence.

It was in Mount Gambier on June 27, 1871, when assistant bailiff Thomas Garroway attempted to seize Jung’s horse and cart in order to obtain money owed.

Mr Garroway’s body was found five days later on the side of the road with two gunshot wounds, including a large wound at the right temple.

Jung was arrested on July 5 and charged with murder.

Historic records say he confessed immediately to the crime and was taken to the Mount Gambier Gaol.

In court, 17 witnesses were called to give evidence, before Supreme Court Judge Alfred Wearing told the jury Jung’s fate lay in their hands.

At the close of the trial, Jung told the court that he had not committed murder and that the gun had gone off accidentally.

It took the jury just 17 minutes to convict him of “guilty of wilful murder” and he was sentenced to death in what was to be the first hanging at Mount Gambier Gaol.

At 8am sharp on November 10, 1871, Jung approached the hangman’s noose “apparently quite free from the slightest feeling of weakness or terror”, according to local newspapers of the day.

Holding a bunch of flowers in his hand, he spoke a few loud and clear sentences in German mentioning that he forgave English law for its severity.

He concluded by saying ‘goodbye’ and asked that the bunch of flowers be given to his “dear wife”.

Elizabeth Woolcock: The only woman executed in SA — 1873

By the age of 25, Elizabeth Woolcock had lived a wretched life of abuse, torment and drug addiction, which ended under a makeshift hanging platform at the old Adelaide Gaol in December 1873.

The only woman ever executed in South Australia, many still believe she may have been innocent.

Woolcock was convicted of the poisoning murder of her abusive husband, Thomas, at Moonta in 1873.

Born into poverty in 1848, Woolcock lived in a crude dugout on the banks of the Kooringa Creek at Burra, until flash floods washed away her family’s home in January 1852.

Woolcock’s father then joined the Victorian gold rush, moving the family to Ballarat.

Just two years later, Woolcock was left traumatised by the bloody scenes of the Eureka Stockade rebellion.

Then, at age seven, she was brutally raped and left to die by a drifter.

Her injuries were horrific and doctors treated the distraught girl with opium, opening the door to a lifelong addiction to drugs.

In 1865, she returned to live in Moonta with her mother and stepfather, where she met and married a widower originally from Cornwall by the name of Thomas Woolcock.

Her husband turned out to be a heavy drinker, a bully and a wife-beater.

Woolcock attempted to leave him several times, at one stage trying to hang herself in the stable.

But the rafter broke, sparing her life.

In August 1873, Thomas Woolcock became ill with stomach pains and nausea.

His wife called in three doctors over the following weeks, who each diagnosed different illnesses and prescribed different medications.

One prescribed a syrup and pills laced with a third of a grain of mercury for a sore throat, while another said he was suffering gastric fever, and a third said the problem was excessive salivation.

But none of the medicines worked, and Thomas Woolcock died on September 4, 1873.

A doctor prepared an initial death certificate blaming natural causes, but then the town gossip cycle kicked into gear.

A cousin suggested he may have died from poisoning — the town knew of Elizabeth’s drug addictions — and she was charged with murder.

After a three-day trial and a jury deliberation that lasted just 20 minutes, Woolcock was convicted and sentenced to death in December 1873.

Just before she was hanged, Woolcock handed her minister a note confessing to the crime.

In the years following her death, some experts decided Woolcock’s confession was religiously inspired and prompted by a desire for salvation by exaggerating her sins.

Proponents of Woolcock’s innocence say her husband’s symptoms were consistent with tuberculosis and dysentery, both of which were found during his autopsy, and the doctor who prescribed the mercury-laced medication was reportedly an addict in a “drug-befuddled state”.

Historian Allan Peters has twice unsuccessfully petitioned for a posthumous pardon, the latest bid rejected by the Attorney-General in 2011.

Flowers are still placed on Woolcock’s Adelaide Gaol grave regularly in tribute to a woman who may have been wrongfully accused.

An arrest, a prison escape and a pardon — 1878

Logic, also known by his Aboriginal name Pinba, was one of South Australia’s most famous prisoners.

He worked as a stockman and boundary rider on the Tinga Tingana station in South Australia’s Far North.

One day in March 1878, Logic and his European stockman partner, Cornelius Mulhall, began to argue.

Mulhall stockwhipped Logic and shot him in the back.

Logic responded by stabbing Mulhall to death.

Escaping arrest by fleeing to Queensland, Logic managed to avoid capture for more than two years.

But in October 1880, the law caught up with him when he returned to South Australia and was recognised.

Tried for murder, Logic managed to downgrade his conviction to manslaughter and was sentenced to 14 years of hard labour — a very long sentence for its day.

Logic was a model prisoner during his time at Yatala and in 1885 a petition seeking a remission of his sentence was prepared.

But Logic had his own ideas.

When an explosion at a quarry where prisoners were working caused a distraction, he took his chance and escaped.

Making his way back to northern South Australia, several local farmers helped Logic evade capture, providing him with food, water, a knife and a blanket.

By this time, Logic had become a bit of a celebrity, with daily letters of support published in local newspapers.

The public called for authorities to cease their chase to recapture him.

Eventually, with the assistance of Aboriginal trackers, Logic was recaptured and transported back to Adelaide.

During the train ride back to town, crowds gathered in large numbers to see the famous prisoner.

They called on the Governor to release Logic from the remainder of his sentence.

Bowing to public pressure, the Governor did just that and in December 1885, Logic was once again a free man.

Until his death in 1903, Logic lived in the Innamincka area in the state’s Far North and — in an amusing little twist — sometimes worked as a tracker for police.

The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of State Records SA with the preparation of this article.

Battle to save animals on the brink at Outback reserve

Conservationists are battling to save animals at an Outback reserve from the effects of the worst drought in recent memory, and have received a funding boost to redouble their efforts.

Country tradie to face court over incomplete work

A country tradesman will face the Elizabeth Magistrates Court over allegations he was not licenced and refused to refund money to clients.