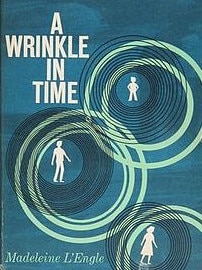

Author Madeleine L’Engle opened her best-loved fantasy with a famously bad line

It had an uncompromisingly terrible opening line but the novel A Wrinkle in time by Madeleine L’Engle, born a century ago today, became a bestseller and had a huge impact on its fans

One of the worst lines in literature is widely regarded to be “It was a dark and stormy night”, which first appeared in Washington Irving’s 1809 work A History of New York. It became the catchphrase for awful writing and one which authors are warned to avoid.

But American author Madeleine L’Engle, born a century ago today, went the other way, using the line to open her novel A Wrinkle In Time. The story of a young girl called Meg who travels through space and time with the help of three mystic women, Mrs Whatsit, Mrs Which and Mrs Who, to find her missing scientist father, is one of the most widely loved works of science-fiction and fantasy.

The cliched opening line may have been one reason the story was rejected by 26 publishers before it was finally printed in 1962. But L’Engle based the book’s stubborn, but intelligent main character on herself, and being as determined as Meg, resisted attempts to change her prose.

It is perhaps why her book resonates with so many women. In Meg, L’Engle created a strong female role model who wins out with both intellect and emotional strength. Her books were inspired by her deep faith, but also a love of science.

While she wrote dozens of other books, A Wrinkle In Time made L’Engle famous. It has been adapted as a play, an opera, a television series and earlier this year as big-budget Disney film with Oprah Winfrey as Mrs Which. But L’Engle was no overnight success, she struggled long and hard before becoming a best-selling writer.

She was born Madeleine L’Engle Camp in New York on November 29, 1918. Her father, Charles Wadsworth Camp, was a writer of mystery stories and potboilers, who had suffered lung damage from a mustard gas attack during World War I.

L’Engle’s mother, also Madeleine, played piano, and both parents were book lovers who read aloud to each other. L’Engle grew up with a love of words, reading widely and writing stories from the age of five.

A quiet, nerdy, bookish girl she was bullied while a student at a New York private school. When her family moved to France for her father’s health, she went to a Swiss boarding school, then when the family later returned to live in Florida she was sent to an all-girl’s school. Her father died in 1936, while she was returning home from a Carolina boarding school.

She studied English literature at Smith’s College and after graduating in 1941 moved to New York where she began to write novels. She got a job in the theatre, where she met actor Hugh Franklin. They appeared together in a production of The Cherry Orchard in 1945, the same year her first novel The Small Rain, was published. It was not successful enough for her to take up writing full time.

In 1946 she married Franklin and her second novel Ilsa was published. Again, not a big seller, but she was determined to make it as a writer and in 1951 published another book, Camilla Dickinson.

In 1952, with their daughter Josephine, the couple moved to Crosswicks, a historic farmhouse in Connecticut, so L’Engle could write. They bought a small shop to bring in money while L’Engle tried to establish herself as an author. After multiple rejections, in 1958, she was ready to give up. In 1959 the family was forced to move back to New York so Franklin could get acting work to keep the household afloat.

L’Engle published Meet The Austins in 1960, which was a modest success, but by then she had conceived an idea for Mrs Whatsit, Mrs Who and Mrs Which. They would become the basis of A Wrinkle In Time. Her first draft was finished by 1960, but publishers either rejected it or insisted on too many changes. She wrote in her journal: “I’m willing to rewrite,

to rewrite extensively, to cut as much as necessary; but I am not willing to mutilate, to destroy the essence of the book.”

Persistence paid off when it was finally accepted by John Farrar of Farrar, Straus and Giroux and published in 1962. It sold millions, won L’Engle the Newberry Medal and allowed her to focus on writing.

She wrote dozens of books, including sequels to Wrinkle and autobiographical works.

She also toured giving lectures and teaching about writing. But her later years were marked by tragedy.

In 1986 Franklin died of cancer. In 1991 she was in a serious car accident and in 1999 her son Bion died of the effects of alcoholism.

Incapacitated by osteoporosis and a stroke in her final years she had to give up her lecture tours. She died in 2007.