Australians were among the Monuments Men who helped recover art treasures stolen by Nazis

WHEN Allied troops recovered Michelangelo’s priceless statue of the Madonna and Child from a Nazi cache in Austrian salt mines, an Australian art dealer was among those who first examined it

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WHEN salt miners in the Austrian alps led American troops to a tunnel of salt mines, Australian dealer John McDonnell was among art experts on hand to examine the most famous

Nazi art loot.

Among 3000 art works stored in the cool tunnels at Altaussee salt mines were Belgian masterpieces, Michelangelo’s Madonna sculpture and Jan van Eyck’s huge altarpiece oil painting, stolen from Flemish cathedrals located just 50km apart.

McDonnell, son of a Toowoomba surgeon, was educated at Cranbrook school in Sydney before being recruited to join international art historians and collectors dubbed “the monuments men”.

Tasked with protecting and recovering millions of art works stolen by Nazi forces on order from Fuhrer Adolf Hitler and German air force commander Hermann Goering during World War II, US President Franklin Roosevelt established the mission 75 years ago today.

American art collectors and curators had agitated for official protection of European art and treasure even before the US entered WWII. Metropolitan Museum of Art director Francis Taylor led lobbying efforts in Washington, where on June 23, 1943, Roosevelt approved the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, then generally known as The Roberts Commission after chairman, Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts.

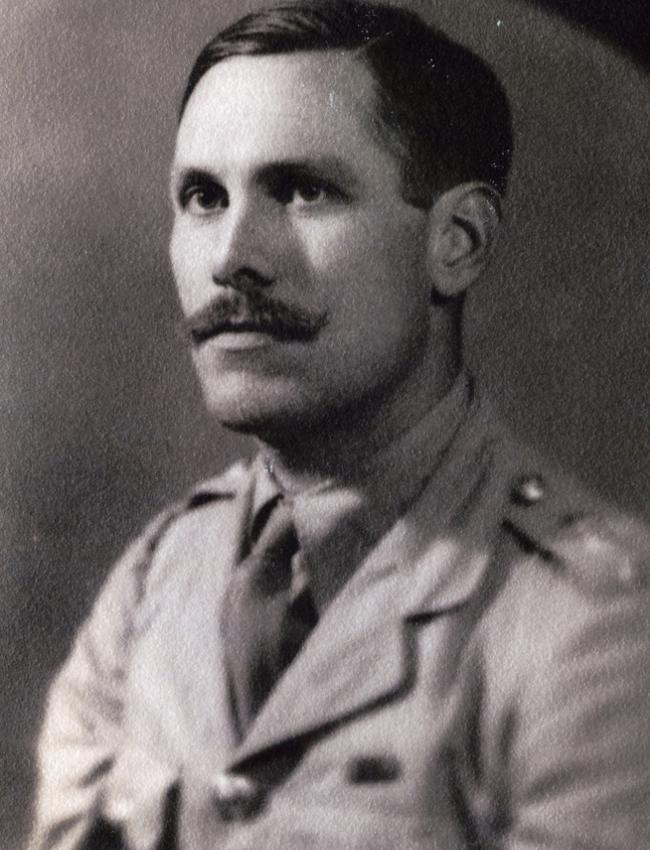

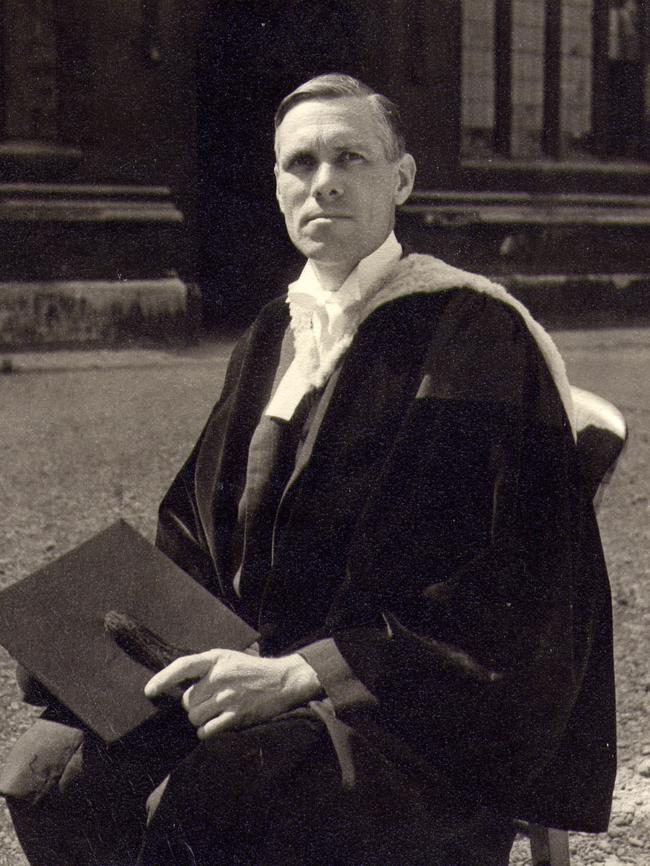

The Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives, or MFAA, recruited 345 experts from 13 nations, including McDonnell and Tasmanian-born classicist scholar and archaeologist Thomas Dunbabin. Educated at Sydney Grammar School, Dunbabin studied archaeology at the University of Sydney then specialised in Greek colonisation of Italy, at Corpus Christi College, Oxford.

At the beginning of WWII Dunbabin joined the British Army, trained as a commando, and in July 1940 was transferred to intelligence. Recruited to the Special Operations Executive in 1941, he sailed to Egypt and was posted to Crete in April 1942.

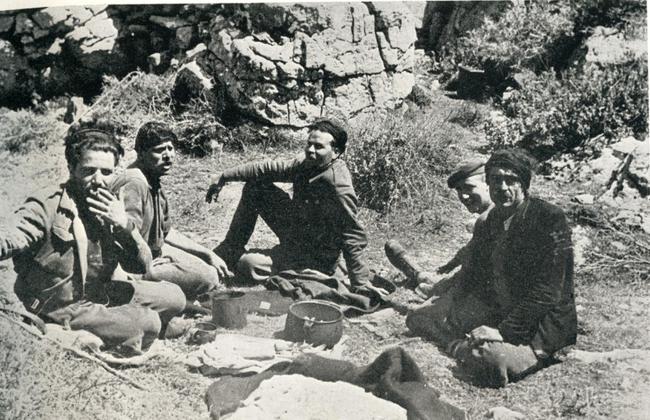

He spent most of the next three years living with shepherds in caves on Mount Ida and in the Kedros Mountains around the Amari Valley. His handlebar moustache, shepherds clothing and near-perfect command of Greek deceived Nazi occupation forces, although his British gait identified him to Cretans who called him “O Tom”.

Dunbabin helped organise local resistance on Crete until German troops departed much of the island in October 1944. He left Crete in early 1945, appointed as the Monuments, Fine Arts and Antiquities officer in Athens to catalogue war damage and Nazi pilfering of treasures from Greek museums and archaeological sites.

McDonnell, full name Aeneas John Lindsay, was private secretary to Queensland governor Leslie Orme Wilson when WWII began. He joined the Red Cross in April 1940, serving in Africa and the Middle East until November 1943.

He enlisted as a lieutenant in the Australian Imperial Force in May 1944 but was seconded for special duties to British forces. With his art knowledge and fluency in French, McDonnell was assigned as an Australian representative to the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) in France in early 1945.

At SHAEF headquarters in London, McDonnell was tasked with creating the MFAA handbook for France, working with US monuments officers, sculptor Walker Hancock and architect Bancel LaFarge.

In December 1944 French art historian Rose Valland, who as an employee of the Jeu de Paume Museum in Paris had secretly recorded the movements of 20,000 artworks and objects stolen by Nazis in France, confided her information to MFAA recruit, former Metropolitan Museum of Art director and curator James Rorer. Valland spoke enough German to understand many works were being sent to Schloss Neuschwanstein, about 120km south of Munich.

In May 1945 McDonnell accompanied MFAA deputy adviser Charles Kuhn on a 10-day inspection of several Nazi art repositories in Germany. He also accompanied Rorimer to Neuschwanstein, where records were stored for 203 private collections from France and catalogue cards for 21,903 confiscated works.

McDonnell was also with art conservation specialist and museum director George Stout, one of America’s first monuments men recruits, to examine the looted Belgian masterpieces, Michelangelo’s 1504 marble sculpture Madonna of Bruges and van Eyck’s huge Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, or the Ghent altarpiece, in July 1945.

The Madonna and Child, displayed at the Church of Our Lady in Bruge, was the only Michelangelo sculpture to leave Italy during his lifetime, bought by wealthy Flemish cloth merchants Giovanni and Alessandro Mouscron for 4000 guilders during a visit to Florence.

The sculpture was first stolen in 1794, when French revolutionaries conquered the area and ordered the people of Bruges to ship it to Paris. It was returned after Napoleon’s final defeat at Waterloo in 1815. German soldiers removed it again at the end of 1944, wrapping it in a mattress before loading it on a train. At Altaussee, Stout built a pulley to lift the 200cm-high Madonna onto a salt cart for its return trip to Belgium on July 10, 1945.

Eight panels of van Eyck’s 15th century masterpiece The Adoration of the Lamb were found behind rubble, resting on empty cardboard boxes about 30cm off the ground.

The 12-panel 5.4m by 4m oil on wood altarpiece was completed by Jan van Eyck and his brother Hubert in 1432, on commission for merchant and Ghent mayor Jodocus Vijd and his wife Lysbette for the city’s Saint Bavo Cathedral. Believed to be the most frequently stolen European artwork, it was reputedly Hitler’s most desired masterpiece.

By July 19, 1945, 80 truckloads carrying 1850 paintings, 1441 cases of paintings and sculptures, 11 sculptures, 30 pieces of furniture and 34 large packages of textiles had been removed from the Althaussee mine.

After the war McDonnell was the London representative for Australian chemist and glass manufacturer Alfred Felton’s £383,163 bequest, split between charities and artistic investments. He died in 1964.

Dunbabin returned to Crete and also worked in Athens after the war ended. He died in 1955.