Anzacs entered Damascus ahead of Lawrence of Arabia

THERE was a great deal of fanfare as the dusty Rolls Royce rumbled toward Damascus. In the car was British officer Lt-Col Colonel Walter Stirling and another British officer, dressed in bedouin robes — Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence.

Today in History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Today in History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

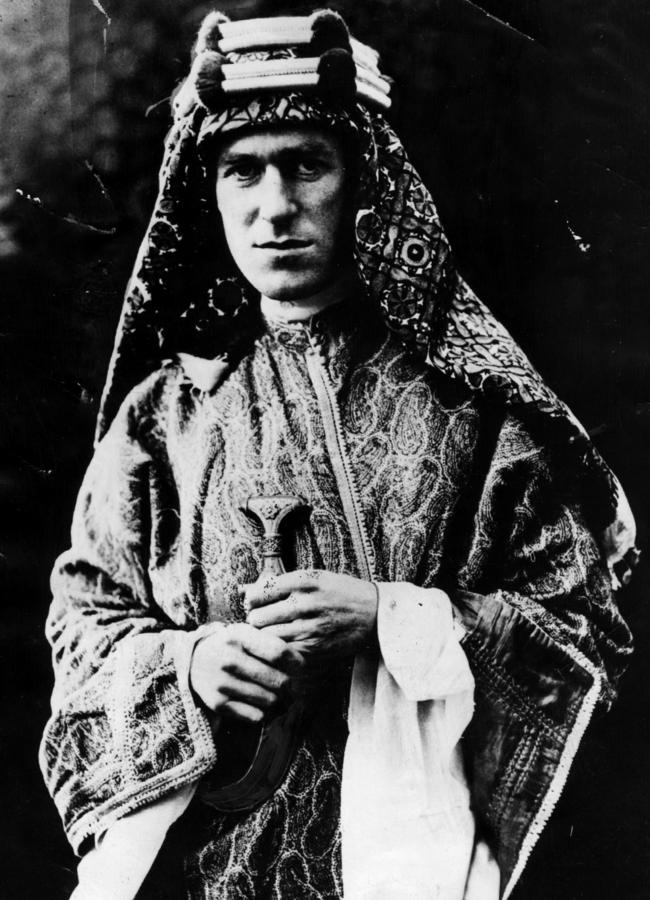

THERE was a great deal of fanfare as the dusty Rolls Royce rumbled toward Damascus. Driving the car was British officer Lt-Col Colonel Walter Stirling. Sitting next to him was another British officer, dressed in traditional Arab robes — Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence, better known as Lawrence of Arabia.

Lawrence’s arrival was to be the crowning achievement of the rebellion he had taken part in against the Ottomans, the moment when he would finally capture the great ancient Syrian capital. But some of that glory had been stolen by Anzac troops.

Lawrence and his Arab rebels had travelled a parallel course with the Anzacs, also fighting the Ottomans, finally joining forces as the Ottomans were rapidly rolled back from their former empire.

Australian and New Zealand troops had found themselves in the fight in the Middle East as a result of the Ottoman Empire’s decision to side with the Germans in World War I. Dubbed Anzacs, they were first sent to Egypt in 1915 ostensibly to train for a Middle East campaign. But while waiting for the main action, they helped British forces repel an Ottoman assault on the Suez Canal in February 1915.

As Ottoman troops tried to cross the canal they came under heavy fire. Only 25 made it across and Egyptian Muslims failed to rise in support of the attack, even after Ottoman Sultan Mehmet V called for a jihad against the Allied troops. It was a bad miscalculation.

But the Allies also blundered when they tried to force the Dardanelles Strait, planning to capture Istanbul and knock the Ottomans out of the war. Lawrence, a former archaeologist, was one of the intelligence officers supplying maps of the region. But through no fault of his, only outdated and inaccurate maps of the Gallipoli Peninsula were available, contributing to the campaign’s failure.

But something happened at Gallipoli that would change the course of Lawrence’s war. An Ottoman officer Muhammad Sherif al-Faroki, taken prisoner during the fighting, told a story about belonging to a secret group of Arab nationalists ready to rebel. The British then decided to incite an Arab rebellion, hoping to undermine the Ottoman war effort.

An influential emir of the holy city of Mecca, Sherif Hussein, also contacted the British to say he was planning a revolt. As Lawrence had a good knowledge of Arabic he was sent to negotiate. He joined the Arab rebel army of Hussein’s son Feisal and urged the British to provide arms, money and other support. The revolt was declared in June 1916, by which time Feisal and Lawrence were already conducting a guerrilla campaign.

In 1917, when Lawrence acquired Lewis light machineguns for the revolt, Sgt Charles Reginald Yells, from South Australia, was sent to teach the Arab army how to use them. British Lance-Cpl Walter Herbert Brooke, of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, instructed the Arabs on the use of trench mortars.

After training Feisal’s men, Brooke and Yells joined the Arab irregulars. Yells played a crucial part in an attack on the railway station at Mudowwara earning him a Distinguished Service Medal, on Lawrence’s recommendation. But many Australian soldiers blamed Lawrence for the Arab irregular’s lack of discipline.

When Lawrence’s forces met up with the Anzacs for the final assault on Damascus — the regional centre for German and Turkish operations — many were sceptical.

On September 30, 1918, as Anzac troops camped outside Damascus, Lawrence arrived in his Rolls Royce wearing his signature Bedouin robes.

But the Anzacs had reached Damascus first, repulsing thousands of Ottomans and Germans fleeing the Allied advance and seeking refuge in the city. Anzac troops had orders not to enter the city “unless absolutely forced to do so’’. But the troops also had orders to isolate the city and the best way to do it was to march directly through it, to block the enemy’s escape route.

On October 1 the Australian troops entered Damascus. They met light resistance but were mostly well received by the city’s Arab residents. On their way through, the Australians refused to take the surrender of the Ottomans.

Lawrence became concerned that Arabs should get credit for being first into Damascus, since they had been promised they could keep territory they had captured. So Lawrence drove into Damascus with Stirling to some fanfare, waving like royalty. He later met his commander, General Harry Chauvel.

The exhausted, dishevelled Lawrence, sporting a hand wound, told Chauvel he was concerned the Anzac march through Damascus might affect the political future of the city and its role in Arab self-determination.

Chauvel was more concerned with keeping order in the city. Wary of the politics, Lawrence would later publish a report that Arab fighters had beaten the Anzacs. He never met Chauvel again, but the Australian commander always pointed out who reached Damascus first.