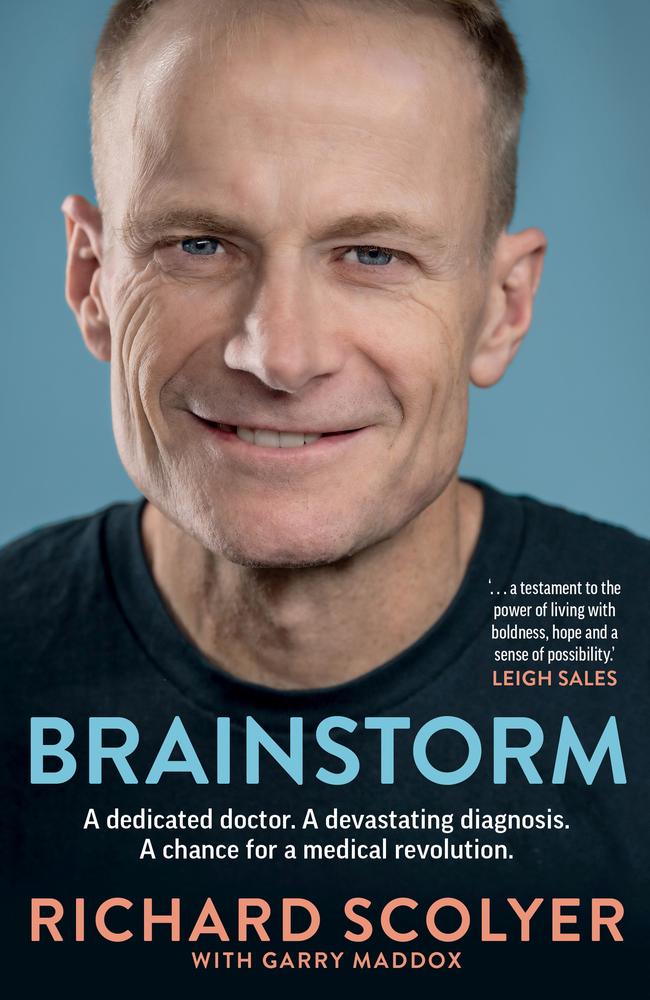

All I could think was: I’m going to die, and there’s nothing I can do to stop it

Melanoma expert Professor Richard Scolyer, the joint 2024 Australian of the Year, was in Poland last year when he woke up feeling “seriously wrong”. This is the terrifying thing that happened next.

News

Don't miss out on the headlines from News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It was a Saturday morning. I was in a hotel in a Polish alpine town – an attic room with a stunning view of the snowy Tatra Mountains.

I’d felt nauseous when I’d woken in the early hours and was no better by the time my wife Katie, who had been asleep in the bed beside me, was up.

As a doctor, this nausea made me uneasy. I wasn’t sure why I felt sick. I was fit and healthy. I hadn’t drunk much or eaten anything dubious at dinner the previous night. I knew the important symptoms of heart attacks and strokes, and I didn’t seem to have any of them. While I’d always tended to play down being unwell – anxious not to worry anyone – I was worried something was seriously wrong.

I was overwhelmed with a sudden surge of nausea. I sensed I was about to pass out. I lay on the floor and mumbled something to Katie about how awful I was feeling.

Katie, who is also a doctor, asked me about my symptoms, checked my pulse and felt my forehead. I started to feel cold and shivery, as if I had a fever of some kind. I wasn’t sure what was happening. I just wanted to lie on the carpet.

Katie was naturally worried. We talked about my symptoms and ran through the possible medical conditions that might be causing them. There were no obvious signs of a neurological problem, no difficulty speaking or moving my arms or legs and no headache, but it wasn’t clear what was wrong.

I wasn’t in pain. I asked Katie to get a bin from the bathroom in case I needed to vomit. We wondered if I might have a viral illness, possibly picked up on my travels.

Katie asked if I wanted to move on to the bed to be more comfortable, but I preferred lying on the floor. She gave me a cushion and a rug from the bed but I still felt cold. I covered myself up and said I’d try to sleep.

As I lay there, I was feeling something that I’d never felt before. I had nausea and shivers but what I didn’t say anything about at the time was that I also felt strange and fuzzy in my head.

I told Katie that she shouldn’t worry too much. That I was fine and she should go out and enjoy the day. But Katie decided to stay with me and it seemed to her that I slept for a number of hours. But inside, all I could think was: I’m going to die, and there’s nothing I can do to stop it. I was panicking. I was scared.

The date was May 20, 2023. We were in Krakow for a conference organised by Artur Zembowicz, a Polish-American professor from Tufts University School of Medicine in Massachusetts. We’d met when I’d organised a symposium at the International Academy of Pathology Congress in Brisbane in 2004. After bonding over a melanoma pathology discovery that we’d been researching independently, we had become good friends.

I slept on and off during the morning while Katie read on the bed.

I only remember fragments of what happened over the next three or four hours.

Katie tells me that at about 1pm I stood up, groaned loudly, bent over at the waist and then pitched forwards on to the carpet, grazing the top of my head as it hit the ground. I had a tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure that probably lasted less than a minute.

Having rushed over, Katie supported me while I lay on the floor unconscious. In the madness of the moment, she couldn’t find either of our mobiles or the hotel phone so she opened the door and yelled for help down the corridor. There was no response.

After checking on me again, Katie went back to the door and yelled “Help!” and “Ambulance!” in the hope that someone would hear and recognise the English words. Two cleaners came running. As they only spoke Polish, they rang for the hotel manager. After what Katie says felt like ages, the manager arrived, saw what was happening and called an ambulance.

At Zakopane Hospital, the results of blood tests and an ECG were normal. While a CT scan appeared to show there had not been a brain haemorrhage, the emergency doctor wanted a second opinion.

Around 9pm, I was transferred in another ambulance, with Katie sitting beside me, to the bigger Krakow University Hospital, 90 minutes away.

The paramedics put on the siren whenever there was any traffic around. I remember feeling uncomfortable at one stage, as if I was being tossed around. On arrival, I was admitted to the stroke unit.

I was met by the senior neurology registrar, a hardworking, extremely capable and caring doctor whose name we never caught. In excellent English, she explained to Katie and me what would happen next. I was sent for an MRI scan of my brain and a lumbar puncture, which draws cerebrospinal fluid from the spinal canal in the lower back.

I arrived back on the ward after midnight and, when Katie, Artur and his anaesthetist wife Margaret left to get back to their hotel, I had an anxious night. I wasn’t in pain but I was scared and exhausted. I knew there was a chance the seizure meant I had a brain tumour. That thought filled me with dread and I slept fitfully.

I was still tired when I woke up early the next morning. A hearty breakfast was served to me but I could only manage some buttered bread and a mug of tea.

About 7.30am, the head of the neurology department, Professor Agnieszka Słowik, arrived with a team of junior doctors and nurses. An incredibly impressive, intelligent and caring doctor who also spoke excellent English, the professor had been to medical school with Artur and Margaret.

She sat on a chair next to the bed, leaned forward and spoke calmly and reassuringly. She showed me the scan and explained that it showed a “mass” in my left temporal lobe that was “most likely a brain tumour”. But there was a small chance the lesion could be a viral infection called herpes encephalitis that was sometimes fatal. In case it was that, she said I needed to start immediate treatment with intravenous antiviral therapy.

I was shocked and found myself falling into a black despair. I realised from the scan and other tests that it was most likely a glioma, a type of brain tumour.

I asked lots of questions about whether the lesion could be anything else, what the expected rate of progression was, what the treatment was. She said I needed a biopsy to get a formal diagnosis.

Professor Słowik’s advice was to get home as soon as possible for the biopsy and treatment.

When the professor and her team left, it felt like my life as I knew it was over.

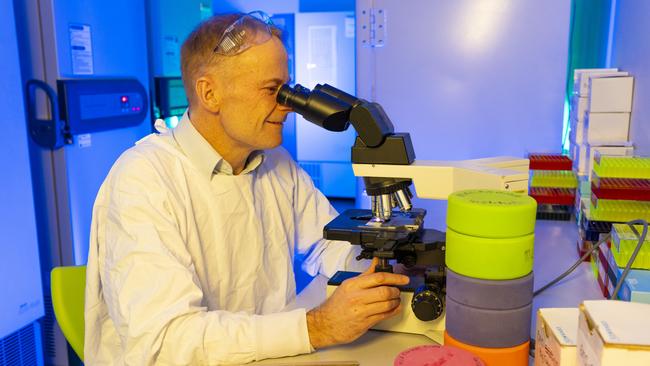

Working as a neuropathology registrar then staff specialist in pathology at Sydney’s Royal Prince Alfred Hospital (RPA) when I was younger, I’d had to diagnose brain cancer many times. I knew the usual outcome for people with a high-grade glioma was shockingly bad.

I felt so many emotions. I was devastated, sad, overwhelmed and despairing. I was terrified it was a fatal diagnosis and anxious about what lay ahead. And when I studied the scan, I was angry that my life was being turned upside down.

It had been a busy year at a rewarding time in my life.

At the Melanoma Institute back in Sydney, we had continued to make real progress in reducing deaths from melanoma, a cancer that is found at higher rates in Australia than in any other country. We were part of a team of world leaders in pioneering immunotherapy, a relatively new form of treatment that uses powerful drugs to supercharge the body’s immune system so it can find and destroy cancer cells.

In 15 years, the five-year survival rate for advanced melanoma had gone from a dismal 5 per cent to a remarkable 55 per cent; tens of thousands of lives around the world were being saved.

We’d made so many advances that, in an outdoors-loving country where once more than 2000 people died from melanoma every year, at the Institute we’d been able to set our sights on zero deaths.

It had been a great time in other ways, too.

I loved my life with Katie, who was also a pathologist, and our children: Lucy was 15, Matthew 17 and Emily 19. They were all well into their educations, with Lucy in Year 10, Matthew getting ready for the Higher School Certificate, and Emily studying health sciences at the Australian National University in Canberra. They were good kids, too – friendly, outgoing, thoughtful and caring.

Despite how hectic it often was, I loved my life.

Now, by myself in a foreign hospital room – with stark cream walls and just a bed, a table and a window overlooking buildings through venetian blinds – I desperately wanted to hug Katie. But there were no tears. I was holding back the overwhelming emotion as I thought through what I’d just been told and what the next steps would be.

While the Polish doctors had been exceptional, none of the nurses spoke English and there was no one to discuss the implications of the diagnosis with. I’d never felt so wildly emotional.

As I’ve said, it was lucky that Katie was with me on the trip. I had been travelling overseas, mostly by myself, up to a dozen times a year for conferences and meetings. If she hadn’t been in that hotel room with me, the seizure might have turned out very differently.

When Katie arrived in the morning, I burst into tears. All I could say, repeatedly, was “I’m

f--ked”. She was crying, too. Katie left the room to call my executive assistant Kara Taylor and our friend Professor Georgina Long – the Melanoma Institute’s other co-medical director – to break the bad news, and to discuss how we could get back home as quickly as possible and start whatever treatment was thought to be best.

I wanted to tell our kids what was happening. So, before Katie had a chance to call them, I FaceTimed Lucy and Matthew, who were being looked after at our place by Katie’s sister Sally. I must have looked a worry, wearing a hospital gown and hooked up to an IV drip in a strange room. Lucy asked about the dressing covering the graze on my forehead and I started crying.

I’d always thought it was best to be honest and open and, in my distraught state, I stupidly told them straight out that I had a brain tumour and the outlook was bad. (I don’t remember doing this, but was mortified to learn later that this is what I said.)

Having thought that their parents were having a brilliant time in Poland, on a rare overseas trip together, they understandably burst into tears, too.

Breaking bad news is a skill that all doctors need to learn.

As my former colleague Professor Chris O’Brien wrote in his book Never Say Die, about being diagnosed with a brain tumour, it was best done with “gentleness, kindness and a sense of hope – that all was not lost and that much could, and would, be done”. In the shock of my diagnosis I’m afraid I lost that perspective, and I apologised later to our kids for how blunt I had been.

That night, I thought through what a brain tumour could do to my mind and body. I knew it could be a glioblastoma, the most aggressive and lethal type of glioma, which was a relatively common brain tumour for men in their 50s like me. At work, I was used to being in control. I diagnosed more than 2000 melanoma and other cancer cases a year.

Suddenly, instead of diagnosing and helping to manage a patient’s life-threatening disease, I had become a patient with a life-threatening disease. I felt like I’d lost control over my life.

More Coverage

Originally published as All I could think was: I’m going to die, and there’s nothing I can do to stop it