Disturbing deepfake trend on the rise as kids feel ‘powerless’ to stop cyberbullies

Educators and cyber safety experts say a worrying number of cyberbullies are using deepfakes to torment their victims, amid revelations up to one in three kids feel powerless to stop online harassment.

Education

Don't miss out on the headlines from Education. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One in three victims of cyber-bullying feel powerless to stop it, a new survey of high school students has found, as educators are forced to tackle a disturbing rise in AI-generated and “deepfake” harassment.

Feedback from more than 1180 students who completed Optus’s eSafety Commissioner-approved cyber safety workshop in NSW, Victoria, Queensland and South Australia found nearly 38 per cent didn’t understand why they were being targeted, while 32 per cent reported that feeling powerless or unable to stop the cyber-bullying was their biggest challenge.

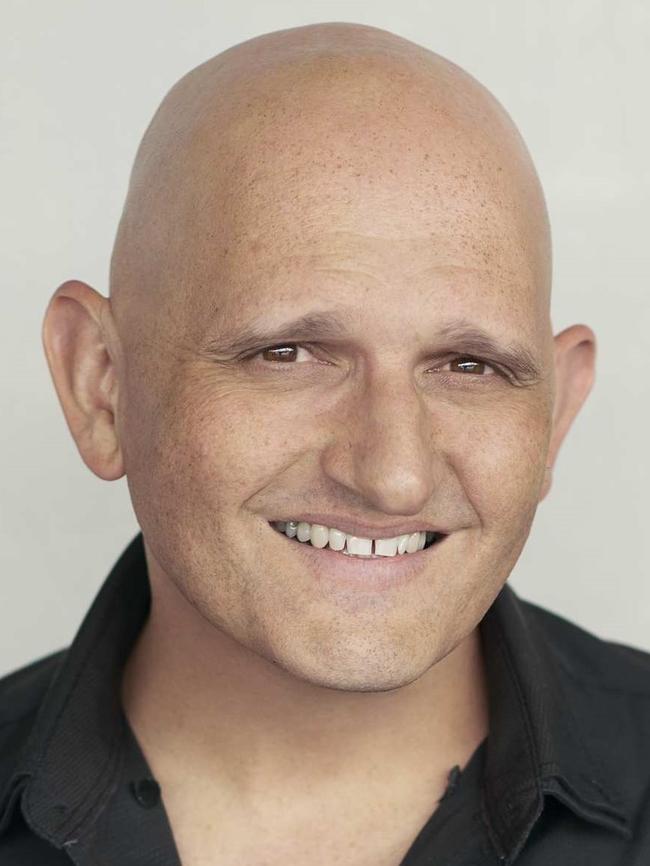

Optus Digital Thumbprint program facilitator Dom Phelan, who has observed a “really worrying” rise in the number of classrooms he visits that are dealing with generative AI and deepfake scandals, voiced support for the Albanese government’s proposed social media age restrictions.

The “sinister” use of photo manipulation and forgery is a cyber-bullying tactic that has only “reared its ugly head” in the past 12 months, he said, with the tools often advertised to kids as a “fun” game on social media platforms like Instagram.

“I wouldn’t say that it’s happening at every school, but I would say it’s starting to happen a lot more — often the teachers will tell me before I come in that this is an issue (they) are facing,” Mr Phelan said.

“There’s often kids that say ‘yeah, someone’s done that to me’ on a TikTok account or a Snapchat account, or sometimes they might get their photos … from the school intranet.”

Mr Phelan said the problem has become so common, lessons on identifying fake news images had morphed into lessons on the consequences of using AI software against their peers.

“A lot of kids don’t realise the damage that they’re doing – once it’s posted online, and shared on social media, a lot of kids don’t realise the enormity of that,” he said.

“(Our program) is about making them understand the damage that they can to, and it often comes back to empathy.”

Leichhardt High School Year 7 students Joshua Jeremy, Lauren Chow, Myraa Bali and Mina McGlashan are among the latest cohort to complete the program in its revised form.

“We learned about deepfakes, which is when you put somebody’s face onto an explicit image,” Joshua said.

“I learned that you have to be 18 to take screenshots or save an explicit photo, even with consent,” Lauren added.

While none of the students had yet encountered pornographic deepfakes or been subject to cyber-bullying, each agreed it was important to learn about the risks at a young age – and how to get help.

“I would stand up for my friends – if somebody else commented on a post my friend just posted badmouthing them – I would stand up and say ‘that’s not all right’, and if I need to, I’d tell the school or a trusted adult,” Myraa said.

“You should be mindful of what you post online – don’t put anything up that you wouldn’t want everyone seeing, because once it’s up there it’s never going to come back down,” Mina added.

“There’s always going to be someone who’s taken a screenshot, or it’s going to be saved to someone’s camera roll.”

The cost of bullying to children’s mental health – and even their lives – has been put in the spotlight following the heartbreaking suicide of 12-year-old Sydney student Charlotte O’Brien earlier this month.

While many factors may contribute to suicide and self-harm, Charlotte’s parents have alleged the young girl was being bullied both in person and online.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese will introduce legislation this year that would ban children from social media, setting an enforceable age limit, the cut-off for which is yet to be determined.

Researcher and child wellbeing expert Dr Joanne Orlando said cyber-bullying remained the number one concern among parents of 10 to 13-year-olds when it came to their kids being online.

“Often (deepfakes) are sent around big group chats, which just get bigger and bigger and bigger, rather than on social media platforms,” she said.

Both state and Commonwealth governments have developed AI “frameworks” for schools, and the creation of deepfake porn was criminalised last month, but Dr Orlando said schools needed to be more proactive in addressing the issue as a form of cyber-bullying.

“Unfortunately, schools’ AI polices are not keeping up with the technology … a deepfake scenario can happen overnight, and it’s something that needs to be addressed very quickly to minimise the harm,” she said.

If this story raised concerns for you, call Lifeline on 13 11 14 or text 0477 131114.

Young people under the age of 25 can access free, confidential counselling online or by phone through Kids Helpline: Call 1800 551 800 or go to kidshelpline.com.au