‘There needs to be more accountability’: Race discrimination commissioner calls out social media giants

Australia’s race discrimination commissioner says mis and disinformation on the internet is a source of racism - and social media companies need to take a tougher stance.

Sydney Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sydney Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Is it possible to end racism?

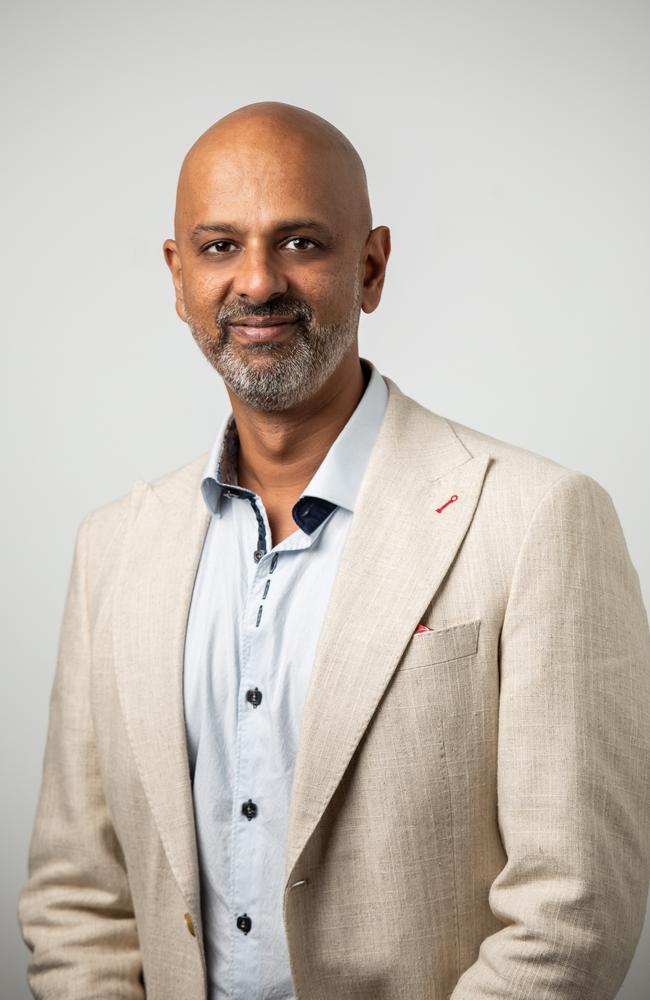

Giridharan Sivaraman believes so – and he has 63 ways to do it.

Australia’s race discrimination commissioner is sitting in his favourite restaurant, Tapri in Paddington in Brisbane’s inner-west, not far from where he lives.

“The food reminds me of home. It reminds me of family,” Sivaraman, 47, says.

As plates of delicious Indian street food hit the table, fragrant with tamarind, mint and chilli, he is quick to point out that while breaking bread – or chapati – together may very well foster connection and delight the tastebuds, it is far from enough to end racial discrimination.

It’s just one of the reasons he’d like to see the focus of Harmony Day – known elsewhere in the world as the International Day for the Elimination of Racial Discrimination – be less about bringing a plate of food to share and more about combating racism through proactive and open discussions.

In November, Sivaraman released the Australian Human Rights Commission’s National Anti-Racism Framework recognising the ongoing impacts of colonisation on First Nations people and the racial abuse experienced by minority groups.

It’s a bold and ambitious vision that includes a 10-year plan to eliminate racism in Australia. While no other country in the world has been able to achieve this yet, many have made significant progress in addressing and reducing the social disease that poisons relationships between individuals and communities across the planet.

Sivaraman took up his five-year appointment in March last year. In this era of misinformation and political polarisation, where hate speech and racism is intensifying, there is much work to be done.

“This is not just an ordinary position. There is only one race discrimination commissioner and it’s a privilege and an opportunity to make a difference to other people that is enormous,” he says.

“We’re in an environment, particularly a political environment, where mis- and disinformation run riot, and mis- and disinformation are often a source of racism.

“We saw that in the UK recently, where pure lies contributed to race riots where Muslim people and immigrants and people seeking asylum were targeted.

“We’ve seen it here in terms of the rise of white supremacist rallies and neo-Nazi rhetoric, which is often underpinned by mis- and disinformation about race, and with racist tropes and lies about people based on race.

“Whatever the outcome, my concern is that in politics and in public discourse, we don’t have a means of actually checking the way in which information is used, and there needs to be more accountability within social media platforms for the use of mis- and disinformation and for racism more generally …. I can’t think of a far-right or extremist ideology that isn’t racially based. That is what leads to people marching in balaclavas on the streets of Corowa (last October).”

Sivaraman is no stranger to racism. Born in India to his Sri Lankan Tamil father and Indian mother, he moved to Zambia before migrating to Australia with his family as a child. His father’s hopes of moving their family to Sri Lanka were destroyed when civil war broke out in 1983. Well before that, racism had thrown his father’s life off course.

“My dad was denied a tertiary education because he was Tamil … Then in 1983, mobs torched buildings, killed people, the family home was burned down, family there were dispersed, and my uncle got shot but he survived. I have a profound sense of the injustice that occurred in my family, but at the same time knowing what injustice is and understanding it motivates you to try and eradicate it. It’s like this splinter in your mind you can’t stop picking at,” Sivaraman says.

Growing up in the diverse western suburbs of Sydney in the ’80s and early ’90s, some of the worst racism Sivaraman experienced came from his school teachers.

“It’s only now, decades later, I realise how wrong it was – the openly racist things they’d say about my skin colour, my name, where I was from. At the time, you’re just a kid and there’s nothing you can do about that, the teacher has all the power. You smile and laugh and pretend it’s not hurting you, but it does,” he says.

Determined to make a difference, Sivaraman went on to complete a Bachelor of Law (Honours) at Macquarie University.

He soon joined Maurice Blackburn Lawyers, where he stayed for the next 22 years and ran offices in Sydney, Adelaide and Brisbane. It was 10 years ago that Sivaraman moved to Brisbane with his wife Lydia, 48, daughter Shanthi, 17, and son, Mithrin, 14, later taking up the position of chair of Multicultural Australia and becoming a member of the Multicultural Queensland Advisory Council.

He resigned from all of these positions to devote himself to the role of commissioner.

The anti-racism framework makes 63 recommendations for a whole of society approach to eliminating racism, including calling on the Australian government to establish a taskforce to implement them.

It identifies seven key areas for reform across Australia’s legal, education, justice, media and health sectors, as well as workplaces and data collection. Following the failed Voice referendum and the abolition of the Queensland Truth-telling and Healing Inquiry, Sivaraman says the framework is more important than ever for First Nations people.

“We still have to have truth-telling and it’s really disappointing that the Queensland (LNP) government has cancelled the truth-telling inquiry. Truth-telling is really significant to racial justice for First Nations people,” he says.

“People don’t even know or understand the full impact of that conversation. I have people say to me, ‘Why should I care what happened 200 years ago?’ but that’s so lacking in knowledge about what really occurred and we need to be educating people about the true nature of our history … It’s hard, but we have no choice but to keep going and try and make a difference however we can, wherever we can.”

It’s an obvious truth for many that racism exists in Australia. The idea that it doesn’t simply isn’t a reality – yet. “Racism is so embedded and ingrained and institutionalised that people often don’t realise it’s there. It’s about power,” Sivaraman says.

“What we want is a society where we all have equity, dignity and respect, regardless of our race or religious background. If you want to get to a society that gets on better with one another, the path to that end is paved with the stones of anti-racism.”

The road to a country free from racism may be long, but we now have a map to get there.

More Coverage

Originally published as ‘There needs to be more accountability’: Race discrimination commissioner calls out social media giants