From Olympic hero to drug dealer: the inside story of swimmer Scott Miller

He was a medal-winning Olympic swimmer, married to a glamorous TV host, but things went from bad to worse for Scott Miller when drugs became his goal. We reveal how an Australian sporting hero’s life unravelled.

Sydney Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sydney Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Olympic medal winner. Social media darling. Drug addict. Pimp. Mastermind of a drug-supplying syndicate. Jailbird.

In his 47 years on Earth, Scott Miller has somehow been all of these things.

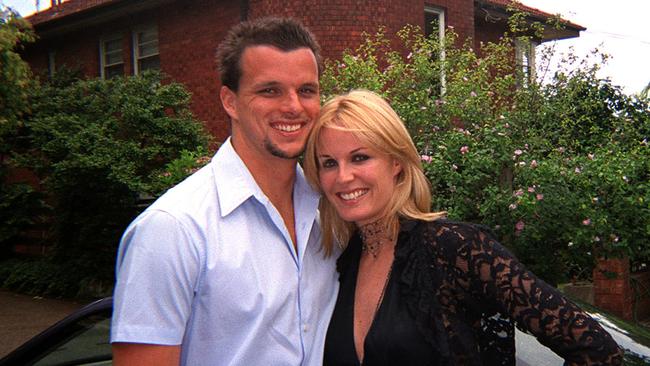

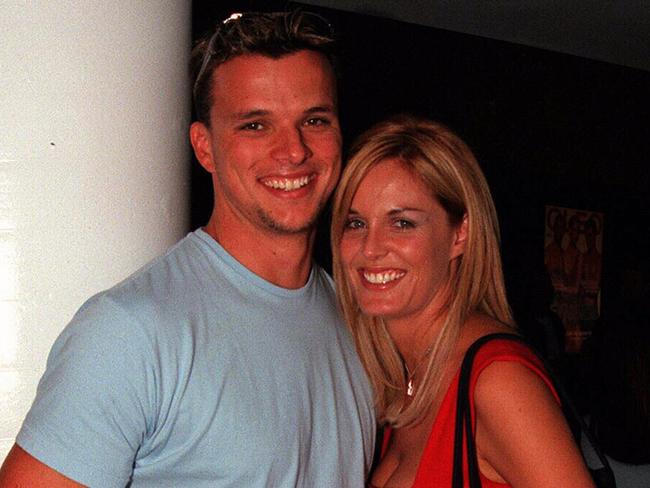

As a celebrated Olympian and socialite in the 1990s, whose marriage to TV star Charlotte Dawson dominated glossy gossip magazines, Miller perfected the art of talking in short, snappy sound bites. Just enough to give the media enough content to craft a story and keep his profile up. But never too much that they were completely let into his world.

Flash-forward to the morning of June 18, 2013 – almost 17 years to the day since he won silver in the 100m butterfly at the Atlanta Olympics – Miller was putting those skills to work. Albeit in a completely different context.

According to police documents tendered to his 2013 court case after he was charged with drug possession, Miller was standing face-to-face with a police officer who had pulled over the famous swimmer’s car after watching it pull out of the driveway of a house in Sydney’s south whose occupants were well known for selling methylamphetamine.

The officer wanted to know what Miller was doing in the house. He also wanted to know why Miller had $2000 cash in his jacket pocket.

There was also another $15,000 cash and a set of scales that the officer was yet to find. Miller was now formulating in his head how he would explain their presence in his vehicle.

Just as troubling were the four small baggies of white powder he was carrying in his wallet that the officer would soon find, the documents said.

Younger generations of Australians who are more familiar with Miller’s drug-related court appearances in recent times may not even be aware of the status he occupied in what now seems like a previous life.

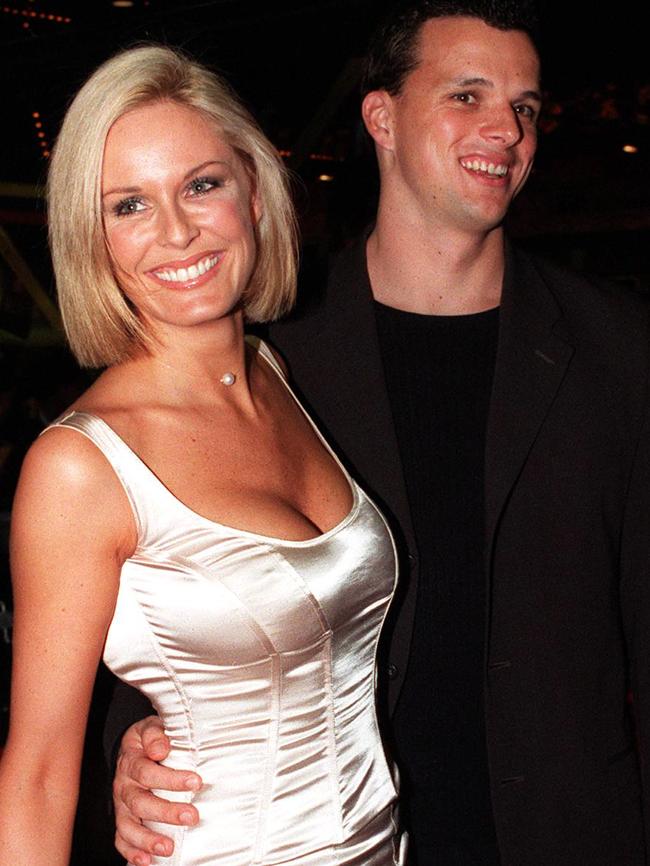

From the mid-1990s to the early 2000s, Miller was one of Sydney’s A-list media darlings. He was tall, good looking, and an Olympian. Heads turned when his six foot four (195cm) frame entered a room or strode down a red carpet.

The aura around Miller only heightened in 1997 when he was named the Cleo Bachelor of the Year.

Two years later, it jumped again when he married Dawson, one of the judges on the Cleo competition and a celebrity in her own right. Dawson found fame as a model and magazine fashion editor and later became a TV personality.

They were the city’s “It couple”. And the public could not get enough.

Rarely a day went by without sightings of the pair at exclusive restaurants and parties. Speculation about their pending nuptials dominated space in women’s gossip magazines and celebrity columns in newspapers. The intense media interest saw Miller become a master of crafting short, snappy quotes.

Forward to June 18, 2013, and documents from Miller’s court case showed he was applying those skills in an attempt to fend off a Q and A with 26-year-old Constable Andrew Booth on Rolfe St, Rosebery.

“Who owns the car?”

According to the documents, Miller replied: “It’s a hire car.”

“Is there anything illegal inside the car?”

Miller: “Look, I don’t know. I was sleeping at home last night and someone borrowed the car. I don’t know who it was, and when I got in the car there were some scales in there. They’re not mine. They were just there.”

The sceptical officer responded: “That doesn’t sound very convincing, to be honest. Surely you would know who had your car.”

Miller shrugged and offered: “You don’t expect me to dob in my mate, do you?”

The officer had heard enough, the documents said.

“Just tell me the truth,” the officer said.

“I’m gonna search the car … so it’s best to be honest at this point.”

Miller played the only card he had left: deny knowledge of anything illegal, no matter how ridiculous.

“There’s 15 grand in a bag in the back seat,” Miller told the officer, according to the documents. “There’s also scales in there as well, but I don’t know whose they are.”

Seconds earlier, Miller had fished a folded pile of $50 and $100 notes out of his jacket pocket and presented it to Constable Booth.

“It’s about $2000,” Miller said. “I carry it around with me.”

The documents said the officer probed further: “Why are you carrying so much cash around?”

“I don’t like having cash at home,” Miller replied. “So, yeah. I just have it with me.”

When the officer asked, “What do you do for work?” Miller’s answer shocked Australia when it was later revealed in court.

It exposed just how far his life had taken a left turn since his days as an Olympic swimming hero.

“I run an escort agency,” the court heard Miller told police at the scene. “I was gonna bank it soon. That’s why I had it with me.”

This was from a man who, at his peak, shared the pool and headlines with a national treasure such as Kieren Perkins, whose gold medal winning efforts from lane 8 at the 1996 Olympics have been adopted into the Australian lexicon as a nationally understood definition of heroism. In fewer than two decades, Miller has undergone a complete metamorphosis and gone in the completely opposite direction to that of Perkins.

While Perkins is chief executive of the Australian Sports Commission and a recipient of an Order of Australia medal, Miller has been arrested for drug-related offences five times since he last flirted with Olympic glory.

On November 11 last year, Miller was jailed for a maximum of five years for leading a criminal syndicate that attempted to smuggle the drug ice, which was secreted in candle wax, and hidden in a secret compartment in a Toyota Camry.

THE OLYMPIC LOSS

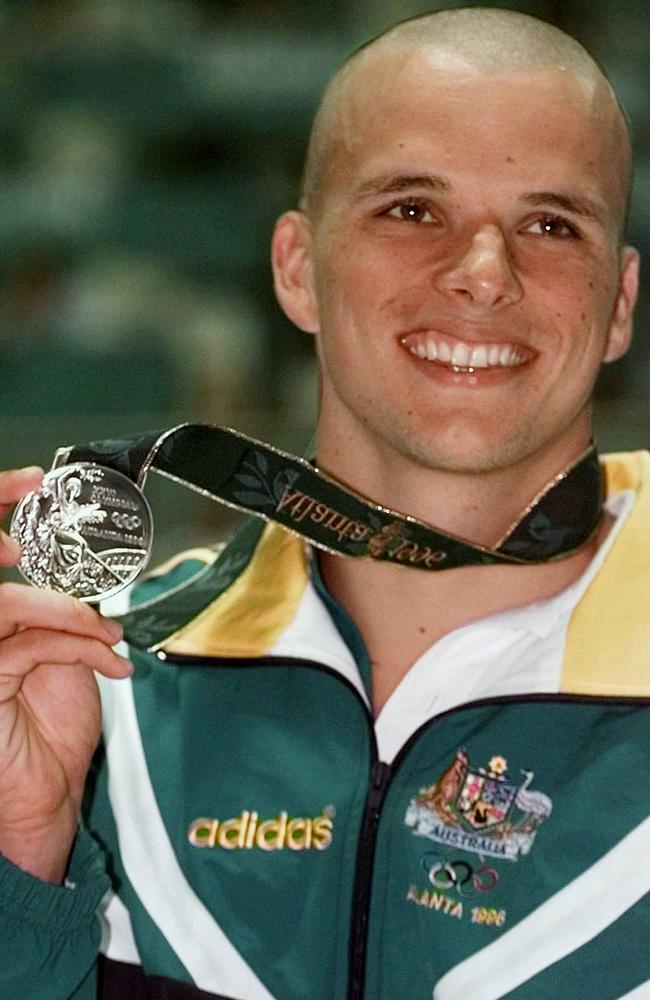

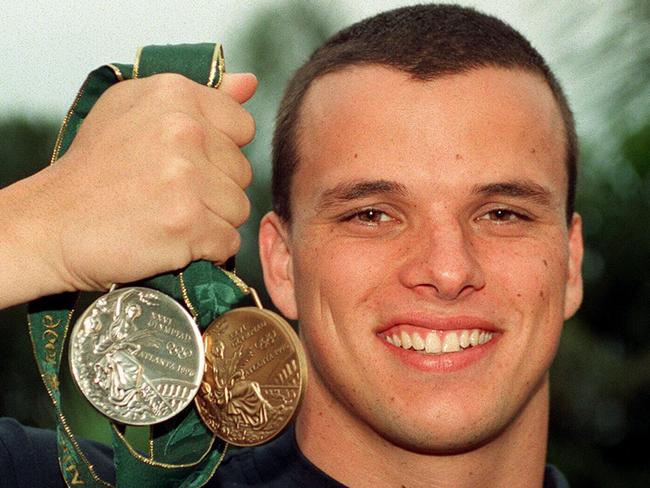

Miller’s hands hit the wall. There was 0.36 of a second separating first and second.

The 1996 Atlanta Olympics were a defining moment in Miller’s life. But not for a good reason. He missed out on the gold medal result he had spent a large portion of his life working towards.

It sent him into a spiral.

Had he travelled through the water 0.37 of a second faster in the 100m butterfly final on July 24, 1996, things might have turned out differently. Instead, he lost.

Miller won silver and he was gutted.

He had been the fastest qualifier for the final and set an Olympic record on the way finishing with a 52.89 in his heat.

But he was beaten in the final by his Russian competitor who employed a controversial method.

Denis Pankratov used what is known as “the submarine” technique where he dived off the starting block and swam underwater for as long as possible using a dolphin kick.

The purpose is simple: you can swim faster underwater than at the surface.

Pankratov was leading the race by the time he surfaced after 35m.

Despite a heroic effort, Miller could not run him down. Pankratov broke a world record that had been set nine years earlier and took gold.

Miller also picked up a bronze in the men’s 4x100 medley relay.

He didn’t know it then, but it was the end of his Olympic career.

His immediate future would be dogged by controversy, injury and the fact that other swimmers – in the form of Geoff Huegill and Michael Klim – were overtaking him.

In 1997, Miller was dismissed from the Australian Institute of Sport after testing positive for marijuana and repeatedly missing training sessions.

He attempted a comeback following his suspension but missed the cut to qualify for the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

And that was it.

After years of staring at a black line on the bottom of the pool, Miller had dipped his toe into the partying lifestyle before his failure to qualify for the 2000 Games.

One report leading up to the qualifying heats noted that the known party boy had swapped beer for cordial to aid his training.

But with his dream now over and there being no reason for him to continue his Olympic-inspired abstinence, Miller was set to blow off some steam.

It was time to party.

And he would soon discover he had a gold-medal appetite for taking drugs.

THE LOVE STORY

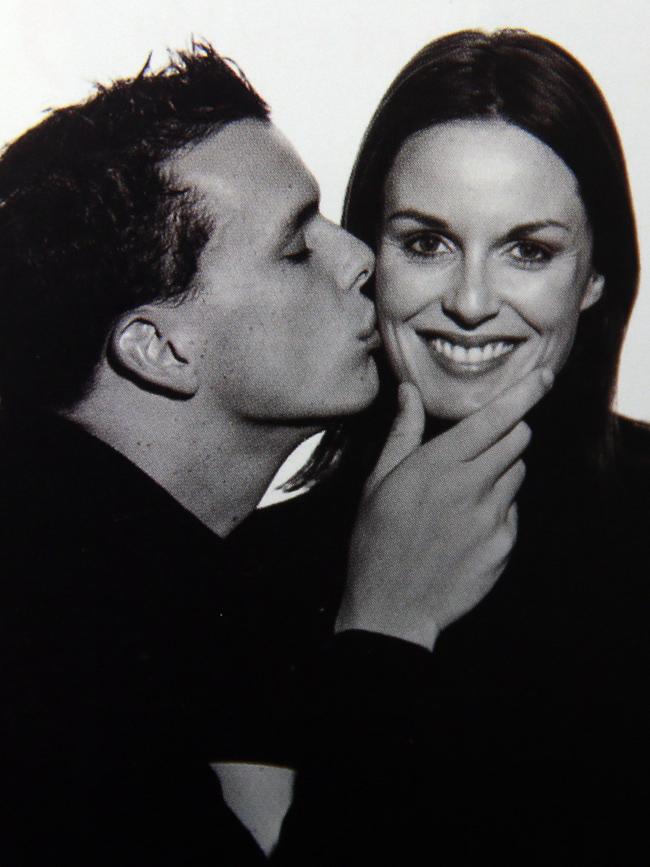

Scott Miller and Charlotte Dawson were married in a manner that fitted the tone of their year-long engagement – the photo rights were sold to New Idea.

As Dawson arrived at Quay restaurant on April 11, 1999, she was shielded by her three bridesmaids who ran a defensive play to block rival photographers – who were not from the Packer-owned gossip magazine – from capturing images.

Miller and Dawson were Sydney’s late-1990s answer to Harry and Meghan – before everyone hated Meghan.

The dashing Olympic hero marries the glamorous model-turned-fashion editor-turned-TV-host.

The public couldn’t get enough.

So Miller and Dawson pumped up the demand and cashed in.

Nothing was too trivial.

The countdown to their wedding was documented in minute detail.

In March 1999, Fairfax published a piece detailing how Dawson’s blonde hairdo, which had been curated for her wedding, had caused drama for a reshoot of the Foxtel and Channel 10 talkfest, Beauty and the Beast, hosted by the late Stan Zemanek.

Two months earlier, a newspaper story gushed that Dawson had stripped down and posed for FHM magazine.

In the accompanying story, Dawson was quoted saying her sex life with Miller was “extraordinary”.

As the wedding day got closer, there were daily updates.

Eight days out: Oxford St club Stonewall transformed into a home cinema for Dawson’s hen’s night, where pre-filmed tributes to the bride-to-be were broadcast.

Seven days out: Dawson’s wedding dress has been designed by Peter Morrissey.

Four days out: The couple to marry at Quay restaurant but the honeymoon on hold because of work commitments.

On the day, the wedding was witnessed by an all-star cast of Sydney celebrities.

The guest list included Matthew Dunn, Charlie Brown, Danny Avidan, Jonathan Ward, Peter Morrissey, Harry M. Miller and Deborah Hutton.

The first report that Miller and Dawson were an item came on December 21, 1997, via the gossip section of The Sunday Telegraph.

Miller was 22 while Dawson was 31.

It was reported the pair had “three dates in five nights”, which included an invitation to broadcaster “Alan Jones’s ultra-exclusive Christmas dinner at his home, where they happily posed for photos for his private collection”.

The following night, they helped christen disgraced stockbroker Rene Rivkin’s new Star City nightclub, The Cave, the report said.

It was tabloid gold.

But it lasted less than a year.

The pair separated around March or April of 2000.

In May 2000, Miller’s Olympic comeback sank when he finished fourth in his qualifying heat.

THE FIRST ARREST

The headline had to be looked at twice just to make sure you hadn’t read it wrong.

Emblazoned across the front of The Daily Telegraph on April 18, 2008, were the words: A long fall from glory to disgrace – STAR’S DRUG BUST.

Olympic hero Scott Miller in drug arrest.

It was an absolute bombshell – Olympic media darling arrested in a drug operation alongside the son of a rugby legend.

Since his swimming career had ended, Miller had worked stints in advertising sales for Sydney radio station 2GB (whose top broadcaster Alan Jones was a close friend of Miller’s), as a car salesman and as a general hand in the horse stables of former Olympic swim coach Brian Sutton.

Drug dealer was not supposed to be on his resumé.

The other man arrested with Miller was Mark Catchpole, whose father, Ken, is a rugby legend and ex-captain of the Wallabies who played 27 Tests and is frequently mentioned as the greatest halfback Australia has ever produced.

Police stormed Miller’s Dee Why home as well as Catchpole’s property in the nearby Northern Beaches suburb of Seaforth in co-ordinated raids.

Miller, then 33, was charged with possessing a pill-press machine capable of pumping out 27,000 tablets in an hour, two counts of possessing restricted prescription drugs and possessing an offensive weapon.

Police also seized capsicum spray and steroids at Miller’s home during the raid.

Catchpole, 40, was charged with knowingly dealing in the proceeds of crime after police allegedly uncovered $224,000 in cash at his home. Illicit drugs including ecstasy, cocaine and ice were allegedly seized.

Police said $200,000 of the cash haul was in 20 separate bundles inside a sports bag locked in Catchpole’s safe. The safe also allegedly contained £500 and an illegal silver Amadeo Rossi .32-calibre pistol with five rounds of ammunition in it.

At the time of the arrest, Miller’s father Barry told The Daily Telegraph that his son and Catchpole had been friends for a long time, but were not necessarily extremely close.

“Scott’s got his mates and Mark’s got his mates,” he said.

Police had been watching Miller and Catchpole for two years and became aware of their activities via a much bigger investigation into the NSW drug trade.

Undercover police secretly filmed Miller at the scene while Catchpole pushed a pill press into a Brookvale storage unit.

The pair had no idea that police had formed an investigation known as Operation Wyadra in late 2006 to target them over suspicions they were involved in a drug ring.

While the shock factor was enormous, the case resulted in fairly minor sentences once the evidence had been tested through the court process.

Catchpole was sentenced to at least five months’ periodic detention for the weapons charge.

Miller avoided jail altogether.

On August 3, 2009, District Court Judge Greg Woods ordered Miller to complete 100 hours of community work and imposed a two-year good-behaviour bond.

This came after Miller pleaded guilty to five charges including supplying a prohibited drug, which related to his admission that he gave 12 ecstasy pills to Catchpole as a birthday gift.

Miller told his sentencing hearing that once his swimming career ended in 2004, he turned to marijuana, ecstasy and partying to numb the pain of “being finished”.

Drugs had ruined his life and any chance of using his sporting success to build a career, he told the court.

The Olympian was entering the next phase of his life.

And it would see him back before the courts again within four years.

SCOTT THE PIMP

Miller’s arrest outside the Rosebery drug house on June 18, 2013, revealed he was trying his hand as a pimp.

Miller had set up an escort agency with his girlfriend Michelle Callaghan, who previously worked as an escort.

Callaghan hit the headlines in 2010 when she was one of two escorts excused from giving evidence in the court case of surgeon Suresh Nair, who was jailed for the manslaughter of a prostitute in a cocaine-fuelled sex session.

According to business records, Miller and Callaghan registered the company name Team Three Pty Ltd in December 2012.

Commercially, the operation was known as Private Escorts, one former employee told The Sunday Telegraph in 2013.

It was located at the escort agency’s address on the 13th floor of the Randstad building on Pitt St in the Sydney CBD.

The outfit was a web-based operation that subcontracted call girls to brothels and also made them available for “outcalls”, a source familiar with the setup said.

“(Michelle) had the contacts to get the girls … (and) Scott is good at maths and IT and managed the websites,” one source told The Sunday Telegraph.

But with demand for such services peaking in the late hours, Miller became a nocturnal creature.

And taking ice was a means of him staying awake, one source said.

Which is why he was carrying the drug in his wallet when he was arrested, the Downing Centre District Court was told.

In November 2013, Miller pleaded guilty to drug possession but told the court the cash was legally earned through his escort agency, meaning two charges of possessing unlawfully obtained goods had to be dropped.

Miller didn’t help his chances of avoiding jail when he was busted with ice in a Potts Point alleyway on July 20, 2013.

Miller pleaded guilty to that too.

In Waverley Local Court on January 22, 2014, he was sentenced to two concurrent one-year jail sentences that were suspended, meaning he could serve them in the community.

Outside court, Miller told the media: “I started rehabilitation in Melbourne; a few months to go, I’ll go back and finish that off, and when these proceedings are finished you won’t see me back here again.”

THE TOXIC RELATIONSHIP

Charlotte Dawson was found dead on February 22, 2014.

It was the day after Miller’s 39th birthday.

Dawson was ruled to have taken her own life inside her waterside rental property at Woolloomooloo.

Reports following her death said she was struggling with a number of intersecting pressures.

There was the fact that her home was being sold by the landlord. One report also said that Dawson felt she was being sidelined from her position as a judge on Foxtel’s reality TV show Australia’s Next Top Model.

The report said Dawson was struggling with the recent tell-all interview Miller had done with 60 Minutes in which he spoke about their relationship along with his drug problems.

Dawson still loved Miller, despite the fact that their marriage had been over for almost 14 years.

Dawson’s death was not a bookend on their tempestuous relationship – instead it continues to haunt Miller.

The swimmer would tell his sentencing hearing for drug supply in the Downing Centre District Court that he blamed himself for her death.

The 60 Minutes interview was not the first time Miller had spoken publicly about his relationship with Dawson.

In September 2000, about six months after their marriage ended, Woman’s Day magazine published a paid interview with Miller in which he claimed his relationship with Dawson had become completely toxic.

In the interview, Miller said his divorce from Dawson had shattered his confidence and accused her of sabotaging his plans for an Olympic comeback.

The pair were married for just 13 months.

Miller also accused Dawson of “emotional and physical abuse”.

In the interview, he claimed Dawson had “publicly punched and scratched him until he bled”. He also accused her of draining their bank account, throwing “a vase through a plate-glass window”, “dumping him by fax while he was away at training camp” and once flying into such a rage that “police had to be called”.

Miller told Woman’s Day their relationship ended around the time he missed the cut for qualifying for the Sydney 2000 Olympics.

“Finally, I walked in the door at the day after missing Olympic selection, feeling pretty down, and Charlotte started screaming at me about what an idiot I was. It was the last straw,” Miller told the magazine.

“I just grabbed a bag of clothes and left. I had to end it because I really couldn’t take any more.”

He also told the magazine that the period leading up to him attempting to qualify for the Olympics drove them apart.

“Charlotte works long hours so I did my own thing,” Miller said. “I don’t drive, so I rode my bike to training, shopped for my own food, cooked my own meals.

“Charlotte did help out when she was around. But I used to drive her up the wall as I’d come home exhausted and just want to sleep. She was frustrated because I couldn’t go out with her to many functions so, at that point, we were two incompatible people. Her lack of understanding of an athlete’s goals was a crucial factor that ruined our marriage.”

Miller told the magazine that the episode convinced him that their short-lived marriage was over.

“Charlotte was so needy,” Miller was quoted saying. “At every turn, I tried to reassure her I loved her. I also had to explain constantly that I was under a lot of pressure and wouldn’t mind a bit of support, at least until I made the Olympic team.

“The stress was incredible. Although I was swimming well, the other part of my life was falling apart and would have exploded in my face if I didn’t get out.”

Unsurprisingly, the story received an explosive response.

On April 2, 2002, Dawson sued the publisher of Woman’s Day, ACP Publishing, in the NSW Supreme Court for defamation over the story.

She reached an out-of-court settlement where ACP paid her $253,000 on May 23, 2007.

THE MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES

Miller’s promise to straighten out lasted for just over seven years.

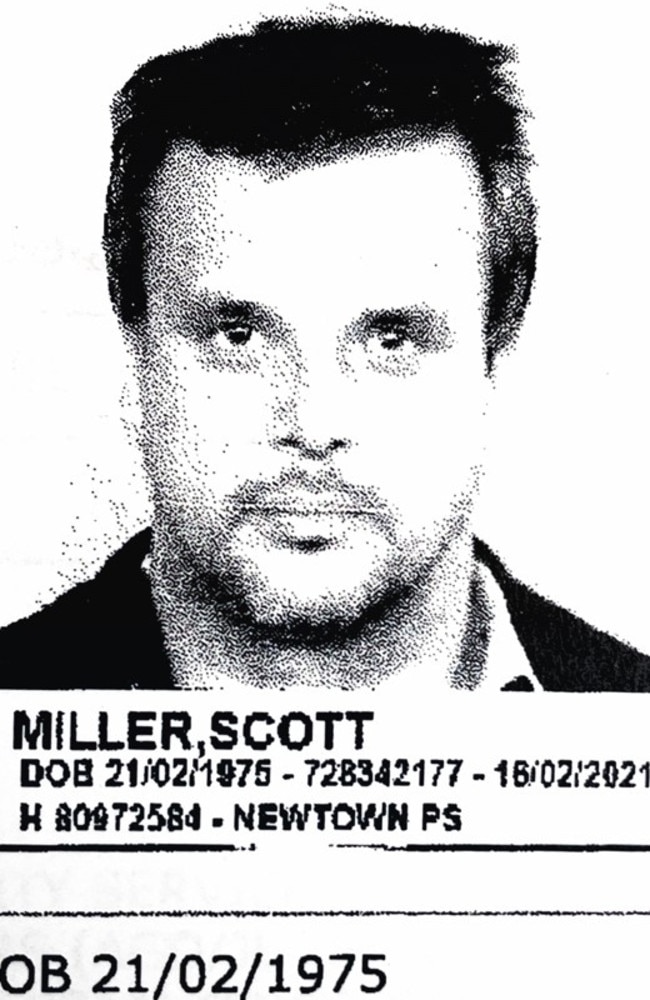

After trying his hand at the rubbish-disposal game, the Olympian was hit with his most serious set of criminal charges yet on February 16, 2021.

Police charged Miller with running a meth-supply ring using a hidden compartment in a hire car.

Miller’s choice of vehicle was – once again – a Toyota Camry, according to a set of agreed facts tendered at his court case.

During his arrest at his Rozelle home, Miller looked nothing like the chiselled Olympian he once was.

Instead, Miller sat on a chair, shirtless in a pair of jeans and thongs with his rotund stomach pouring over his beltline.

The court documents said Miller was at the centre of a group that moved 4.4kg of the drug ice.

Police put a tracking device on Miller’s car and monitored his movements for several days. Court documents said Miller met a man in January 2021 who placed $2.2m of the drug in his car.

The drugs were then hidden in a secret compartment that had been built into the car, the document said.

Miller and another man then drove the drugs to Yass, where they met two other men in a motel.

The two other men dumped the candles during a car chase with police.

The officers recovered the drugs and arrested all four men.

Police also found 800g of heroin, $72,000 cash and mobile phones when they arrested Miller.

Miller pleaded guilty again – this time to two counts of supplying a prohibited drug, dealing with property proceeds of crime and participating in a criminal group contributing to criminal activity.

In the Downing Centre District Court, tendered psychological material attempted to explain why Miller had taken such a self-destructive path in his post-Olympic life.

In a nutshell, it said that Miller experienced what many athletes suffer in the post-competing career.

Everything he had dedicated his life to was suddenly ripped away, the material said.

He had no routine to keep to because he didn’t need to train.

He was back on life’s starting line with his sporting prowess now useless to him when it came to earning a wage.

And there was no reason to abstain from drugs and alcohol, which he hit hard.

Miller’s lawyer Arjun Chhabra told Judge Penny Hock that his client had suffered a “public comedown” in his post-swimming career and he had been left “ill-equipped to move into a life beyond his sporting career”.

Judge Hock told the court the tendered psychological material showed Miller’s “mental health issues commenced” when he was accepted into the Australian Institute of Sport as an elite sportsman.

“He was devastated he didn’t win gold,” Judge Hock told the court while reading a character reference tendered for Miller.

“This was the level of expectation he placed on himself.”

Material tendered for Miller also said that he blamed himself for Dawson’s death and that it had also sent him into a spiral.

On November 11, Judge Hock sentenced Miller to a maximum five years and six months in jail. He will be eligible for parole on February 15, 2024.

EPILOGUE

The story presented by Miller’s legal team in court about his fall from grace points to one theme.

Athletes such as Miller who dedicate their lives to pursuing Olympic glory are often set up for failure.

While they perform at the absolute highest level, it is only for a tiny amount of time.

Miller is not alone.

The list of athletes who have lost their way after failing to find direction in the second stage of their life is long.

And the question Miller now faces is whether he still has any connection to his identity as a celebrity and Olympic hero.

The alternative is that he has spent so long in the world of drug dealing that he is an institutionalised criminal.

Lifeline: 13 11 14

Beyond Blue: 1300 22 4636

Kids Helpline: 1800 55 1800