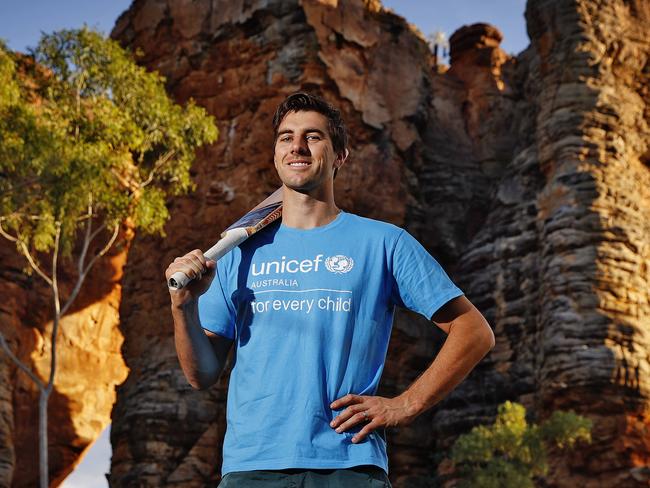

Australian cricket captain Pat Cummins opens up about his work for UNICEF and the Borroloola community

Some want Pat Cummins to stick to cricket, but the Australian captain doesn’t care about the flak he cops from critics and is desperate to make a difference on the issues that he cares deeply about.

Sydney Weekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sydney Weekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

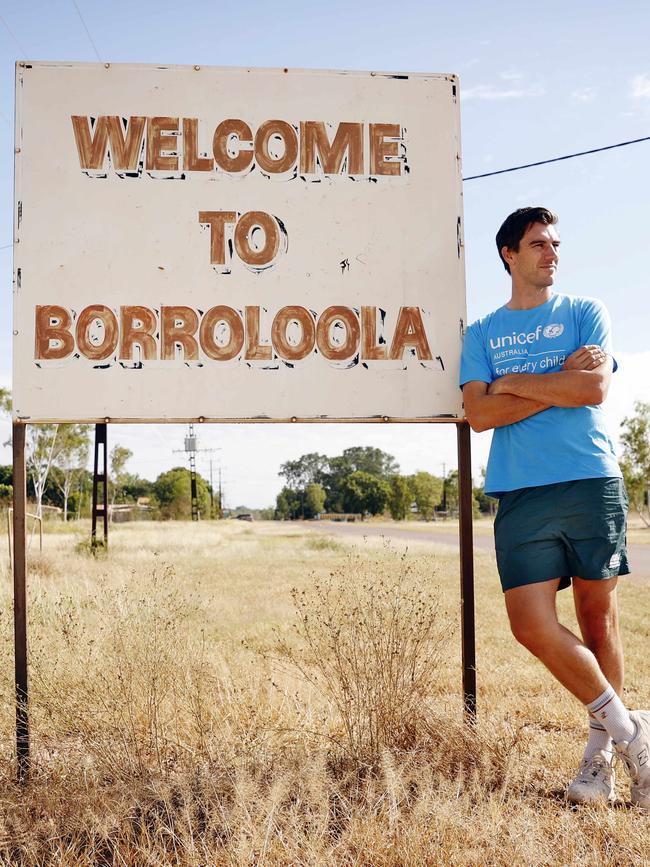

In a tiny town far from anywhere, where talk of giant crocs in relation to how the barramundi are running comes before the weather, something extraordinary is happening.

Thanks in part to two Australian sporting greats – one long retired and one a legend in the making – the lives of some of the children of Borroloola are being turned around.

On every marker the disadvantage in this Northern Territory outpost on the Gulf of Carpentaria far outpaces the rest of the nation.

One of Australia’s most remote and marginalised communities, with 50 per cent unemployment among its Indigenous population and 66 per cent of its children classified as vulnerable compared to 11 per cent nationally by the Australian Early Development Census, the challenges for the leaders in Borroloola are monumental.

The situation here and in other remote Australian communities is so confronting that UNICEF, known for protecting children in disaster zones the world over, has established Australian operations there.

Its key focus in Borroloola is early childhood development and the UN body’s partnership with the Moriarty Foundation, named for the first Aboriginal Australian representative soccer player John Moriarty, is largely funded by one donor: Australian cricket captain and UNICEF Australia ambassador Pat Cummins.

While Cummins doesn’t want to talk specific figures, UNICEF says his significant and ongoing contribution to the locally-run Indi Kindi has helped it prosper here and also to spread into Tennant Creek, 780km south, and another community.

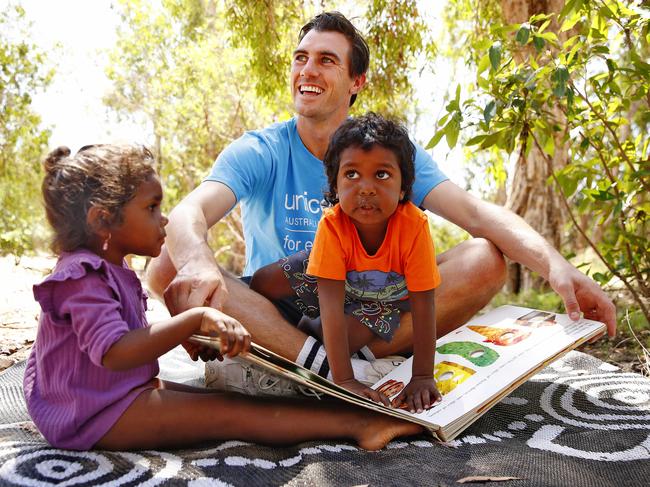

The daily preschool sessions, entirely Indigenous run and taught outside or “on country” in both English and local languages, have had a marked difference on the educational outcomes of children here.

Sydney Weekend was invited this month to join Cummins on his first visit to Indi Kindi – where he signed on after the birth in October 2021 of son Albie with wife Becky.

“Initially I joined because of how lucky we felt we were to have had a healthy baby and for him to have so many opportunities,” Cummins says.

“We just wanted to try and help give other children similar opportunities.”

The word remote doesn’t do justice to Borroloola, 50km upstream of the Gulf on the McArthur River near the Northern Territory border with Queensland.

With a population of about 800, 74 per cent Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, it’s a two-and-a-half hour light plane flight or 12-hour drive from Darwin or 14 hours from Alice Springs. It’s so far away and with needs so unique that within that word remote are contained multitudes.

“Once you spend some time here and you hear the stories from people here, you realise how tough it is to get ahead,” Cummins says.

“This is a really tough place to live. For everyone really. For children trying to get an education, for their fathers and mothers trying to get jobs and give their children the best start.

“So this visit has been really moving. It all feels so far away from what we experienced growing up.”

Travelling for cricket has given Cummins perspective and insight into highly challenged communities all over the world. But parts of what he saw in the NT were similarly confronting, such as the impact of alcohol abuse, generational unemployment and preventable health issues such as deadly rheumatic heart fever or common glue ear causing hearing damage.

“I think people don’t realise that things are so bad in parts of Australia,” he says.

“That’s really hard to take as an Australian, knowing that these things are happening in parts of our country. Things that we don’t even think about in Sydney or wherever we are. Health care is tough to get in these regions and hearing these stories made me realise how far we still have to go.

“That’s why programs like this and the incredible work that UNICEF and the Moriarty Foundation are doing are so important.”

When he was just four in 1942, half-Irish Borroloola boy John Moriarty went away to school at Roper River and didn’t come home.

Despite a search by his uncles who travelled on cattle trucks as far as Sydney to bring him back, it was another 11 years before he again saw his mum, standing over the road from him in Alice Springs.

“I saw this woman and she asked me my name and where I was from. I said Borroloola and she said, ‘I think I’m your mum’,” Moriarty recalls, still emotional all these years later.

“We sat down on the side of the street and we talked and talked.”

One of tens of thousands of members of the Stolen Generation, Moriarty, now in his 80s, went on to play soccer for Australia, was a senior public servant and, with his wife Ros, started the Balarinji design studio, which has received extensive accolades and is best known for creating the iconic Qantas planes bedecked in Indigenous art.

At the request of senior Aboriginal women in Borroloola, the Moriartys established the Moriarty Foundation in 2011. It has run Indi Kindi since 2012 as well as a series of other programs that between them are achieving progress in 13 of the 17 Closing the Gap targets identified by the Productivity Commission to improve outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

“That is why we set up Indi Kindi, so that other kids don’t get taken away from their mums,” Moriarty says. Ros says female leadership was key to the program’s success.

“Women in traditional communities or in these remote communities are often primary caregivers for everybody,” she says.

“And so it was a logical step that when we recruited into Indi Kindi that it would be 100 per cent women and 100 per cent local. And what started as a job they have taken as a path to leadership. And they are much more than employees of an organisation. They are very dedicated educators.”

Pointing out that learning in classrooms can be challenging for sufferers of glue ear because “the sound of voices bounces off the walls and are hard to hear”, she says that teaching outside was also important.

“It’s a really different way of learning that suits their children and these women are best placed to deliver it,” she says.

Some 80 per cent of the town’s children aged under five go through Indi Kindi’s classes that start on a dry riverbed each day.

Classes are taught in English and Yanyuwa, which is one of the Indigenous languages of Borroloola and, weather permitting, they are all taught outside.

As well as the usual preschool activities of art, sport, literacy and numeracy, the children are fed a hot meal, have basic health care and are picked up and dropped off each day.

Educator and mum-of-two Deandra McDinny, 33, couldn’t be more proud of her role in the program, which has given her a career that included helping to teach her own boys.

“When I grew up here we didn’t like going to school but now the kids race for our bus,” she says.

UNICEF Australia’s head of program partnerships Toni Bennett says that Australians are often surprised to learn how extensive local programs were for the international organisation.

“Obviously UNICEF works around the world in 190 countries, but what many people don’t know is that we’re actually here in Australia and the way we work overseas is exactly the same way as we work here, and that’s in partnership,” she says.

“We partner for impact and we target the most vulnerable and marginalised children.

“We work with the Moriarty Foundation because what they do is really best practice, run locally and with the women of the community being the leaders.”

She says that the work would be impossible without support such as that offered by Cummins.

“UNICEF is 100 per cent donor funded and so we urgently need funding to support us, whether it be us responding to an emergency in Syria or a drought in India or something here in Australia,” she says.

“With the support of Pat coming in, what it’s enabled for us is to support delivery here and also expand to new communities.

“UNICEF has many amazing, generous supporters and they support a number of programs … but Pat is pretty special and unique.”

The dusk brings a slight but welcome dip in temperature as dozens of kids aged from primary school to teenagers form a rowdy rabble on the grass oval next to the local school.

The Moriarty Foundation runs soccer training here every day after school, as well as PE programs in school and holiday camps. There’s also a coach training program which is staffed by local Indigenous men and women – with full gender parity. This program has produced a Young Matilda (Shadeene Evans) and a handful of other kids have travelled on to professional sport careers, including in the AFL.

Some of the kids don’t seem to want to go home when it’s over. Fed a hot dinner cooked by their coaches at the end of training, sitting on a mat in the twilight, for many it’s the only meal they will get today, just as with the younger kids at Indi Kindi.

As a football town – both the round type and AFL – many of the children here don’t know who Cummins is when we arrive with a camera and a crew of blue T-shirt wearing UNICEF staff. Asked if he’s a famous soccer coach, Cummins’ grin is wide as he shakes his head and says, “No mate, we’re just here to visit.”

Back in Darwin as part of our two day NT tour, Cummins is polite to the punters who regularly approach him for a chat about cricket, but he jokes that being clearly unrecognisable to the kids of Borroloola was a highlight of the trip.

Cummins obviously has a fairly intense day job, but he took this trip a few weeks before heading to the UK for the Ashes because he believes passionately in the work that UNICEF and the Moriartys are doing.

“I think a lot of Aussies find this stuff hard to talk about or prefer not to think about it, but you come out to these kind of areas and you realise just how important it is,” he says.

Cummins, who supports a Yes vote in the upcoming referendum over an Indigenous Voice to Parliament (“it’s a no-brainer”), also knows that not every Australian is overjoyed about him speaking on things that aren’t just cricket. Asked if he thinks Aussies need to be made to feel “uncomfortable” in order to effect some change he is emphatic that this is the case.

“I think that some things are too important to worry about how people feel,” he says. “Through cricket I get to travel all around the world. And you think a lot of the problems you hear about overseas aren’t here in Australia. But there are still groups that are up against it and I think it’s our duty to try and help.”

As for critics who say they don’t want him to speak out, Cummins is unapologetic.

“If you do anything you get criticised and if you do nothing, you get criticised, and it doesn’t really bother me, to be honest,” he says.

“I think, with the work that has been done in these kinds of places and being in a position where I can help, well, that’s way more important than copping a bit of flak occasionally from people that don’t want to help.

“I just think these kinds of programs are too important. There’s so much good that’s being done by different people and organisations and great stories within that, that if I can help, and if people have a problem, well, who cares, really?

“I just hope that people listen and are open minded to different stories. You know, sitting back here the last couple of days and hearing John and Ros talk about their experiences, listening to the Elders and the teachers, I think they’re really important stories.

“And I just think, you know, that all of us have a duty to sit back and listen and learn. And if we can do one thing differently, it will be better. I think that’s only a good thing.”

■ The author and photographer were guests of UNICEF Australia. To learn more or to support UNICEF Australia and Indi Kindi, go to unicef.org.au/indikindi