What it’s like to be a member of Westboro

Westboro Baptist Church is notorious for its shock protests and apocalyptic world view. Now former member Megan Phelps-Roper has revealed the depths of the power it held over her family — and how she escaped.

There was a time when Megan Phelps-Roper’s entire life revolved around the Westboro Baptist Church, the Kansas religious group notorious for its public protests against the gay community, the military and more.

Phelps-Roper spent most of her days picketing with her family and her nights at the coalface of the church’s social-media platforms.

It was her online interactions with “enemies of the church” that ultimately led to her deradicalisation. She left the church — and everything and everyone she knew — in November 2012. Since then, the former Westboro member has become an advocate for people and ideas she was taught to despise.

On the morning of my high school graduation, my brother disappeared. Saturdays were as welcome in my house as they are anywhere, and that one — sunny, warm, breezy — seemed like the perfect start to summer.

Still in pyjamas, I was the first of the sisters to slip into the kitchen, which was brightly lit and full of activity.

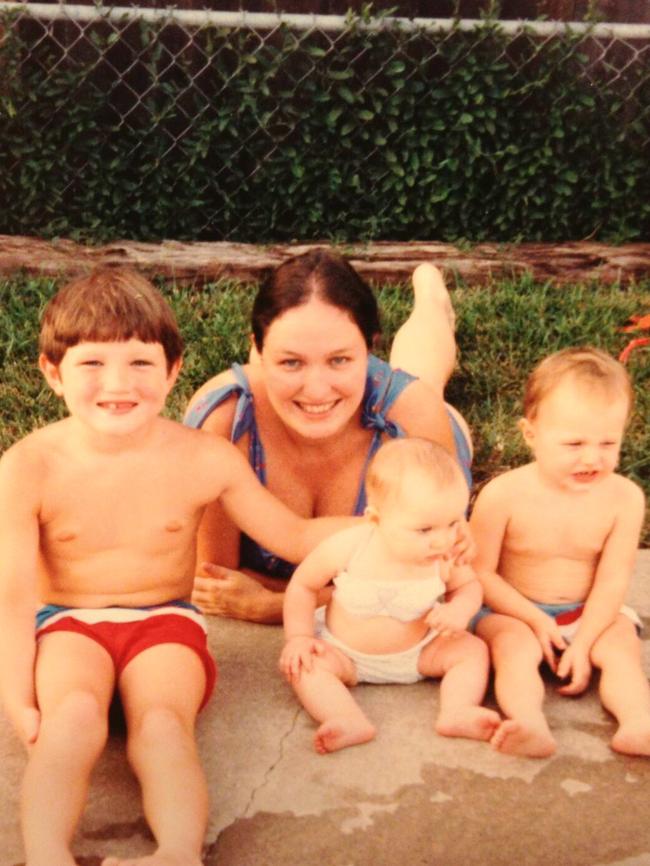

Mum was standing over the stove making breakfast and singing a ’70s pop song I’d only ever heard in her soprano. I heard the huge smile in her voice before I saw it, and when she turned, her eyes caught mine and then she was singing the love song to me, with exaggerated feeling and theatrics at full voice.

“Where is Josh?” she called over the din. “It’s getting late. Would one of you boys run down and wake him up?”

My brothers tumbled over themselves to race down to Josh’s basement bedroom. Moments later, they were thundering back up the stairs, Jonah leading the pack.

“He’s not there! It’s all gone!” Jonah was seven and a little confused, but not worried. I wasn’t, either; bizarre declarations were par for the course in a family with eight brothers.

My brow furrowed a little, and I looked to Mum, whose mouth was ajar.

“Would you...”

“I’ll do look,” I said, and headed for the stairs with three little brothers trailing. There were 14 steps down, and with each one, more of the stripped basement came into view.

The television was gone, and so was Josh’s beloved Xbox. The bookcase, too. No clothes or random knick-knacks strewn about.

It had been years since I could see this much of the blue carpet, and I wondered briefly if he’d cleared the place out for the carpet cleaners. I was reassured to see that the dresser was still there and the bed neatly made.

He was probably just in the shower. The boys flung open the flimsy double doors of his closet, and time slowed down. The shelves and racks were completely bare.

One of the boys suddenly thrust a white envelope he’d found into my face. “Go show it to Mum,” I said, waving him on. They all took off. I checked the bathroom, just in case.

“MUM AND DAD, I didn’t think I would ever be saying this...” The letter was one page, single-spaced, Times New Roman font, size 12, dated May 21, 2004.

The day before. He must have left in the middle of the night. I knew that meant he was a coward, like two uncles of ours who had left the family long before any of us were born. Their reasons for leaving the church could never be valid; just paltry attempts to mask the fact they were wretched creatures controlled by their lusts — dastardly, selfish, unable to hack it in the rough and tumble of the Wars of the Lord.

The implication of my mother’s tales of her departed siblings had always been abundantly clear: these deserters were not like us, and we were better off without them.

We all knew this, but my mother had never been the sort of parent to let a lesson — or anything, really — go unsaid. Still standing over the stove, she was only quiet for a moment after she read through the letter.

All four little boys were clustered around her, hushed now, waiting to be told what was going on, where Josh’s stuff had gone.

Her tone was sober, and there was finality and resignation in it: “They went out from us, but they were not of us.” She was quoting the Bible, I could tell, but this wasn’t a verse we’d focused on before and I was as mystified as the boys.

I couldn’t pay attention anymore, though. My thoughts were racing. My 19-year-old brother had gone apostate.

We’d been together since my birth precisely 17 months after his, but I’d never see him again. I’d never speak to him again. He hadn’t said goodbye. Why did he leave? Where did he go? What was our family without him? I tried to imagine our house without his near-constant recitation of esoteric movie quotes, and failed.

I tried to imagine never again standing on the picket line discussing the philosophical questions raised by Stephen King novels, and failed.

“Can I...?”

I reached for the letter, and Mum passed it over. I read through it once, and then again, hoping repetition would reveal why he’d done this drastic thing.

He had a wide array of complaints — rejections of everything from the church’s picketing ministry to the way our parents ran our household — but at first, none of his grievances made any sense at all.

I paused briefly and reconsidered: I could appreciate some of his grumblings, but none of them was a reason to leave the only known place in the world where God meets with His people.

There was one part, though, that I simply couldn’t fathom.

“We picket these people and they hate us for it and I have had enough of it.”

I shook my head as my eyes traced that line again and again. I knew there were some difficult parts of the life we’d been living, but being reviled wasn’t one of them.

The fact that people hated us was cause for great happiness. Jesus Himself said so: Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.

Dismayed, I set the letter down on the counter. Maybe Josh really was a coward.

Long ago, I had dedicated my life to serving God and His people, and I would not be like Josh and draw back. I would not follow him to destruction.

MORE STELLAR:

Ita Buttrose: ‘I hope the government is listening’

Meet David Campbell’s alter ego

Josh was wicked, a coward. He wanted the praise of the world, he’d said so himself. He had denied Jesus, trodden underfoot the son of God.

No, I was not like Josh. My heart was fixed.

I will never leave this place.

This is an edited extract from Unfollow by Megan Phelps-Roper (Hachette Australia, $32.99), which is out now.