The diagnosis that changed Bryan Brown’s life

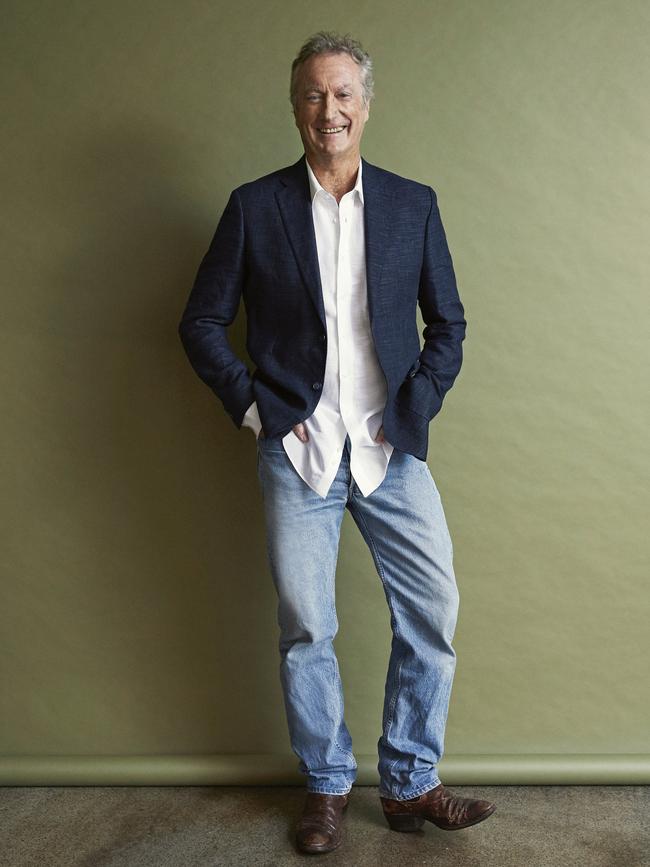

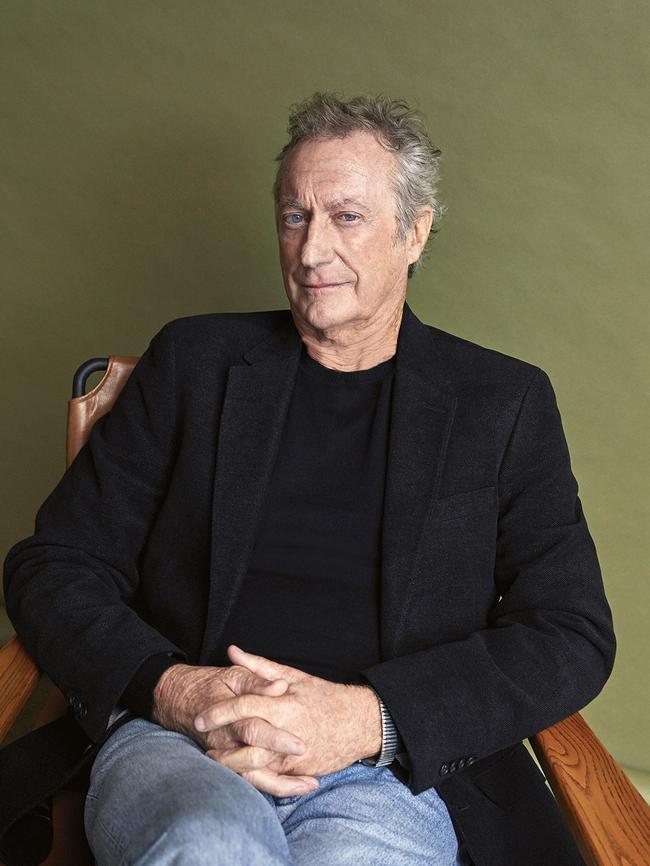

He has long been a sturdy onscreen symbol of Australian manhood. But as actor Bryan Brown’s new passion project resulted from an alarming brush with his own mortality.

The idea that Bryan Brown could be unwell, fallible even, was difficult to comprehend.

After all, Brown had epitomised an idealised version of the Australian male onscreen since the 1970s: strong and bronzed, with a Chesty Bonds jawline and a disarming ease with our vernacular.

When filmmakers got to work casting The Shiralee, they found their quintessential swagman in Brown. When Two Hands director Gregor Jordan needed the perfect Sydney gangster, he also turned to Brown.

Yet Brown’s latest film, which he produced and his wife Rachel Ward directed, came from a time when he was broken.

Palm Beach stars Sam Neill, Greta Scacchi, Richard E. Grant and a scene-stealing Heather Mitchell as a group of 60-somethings assembling in Sydney’s idyllic Northern Beaches to celebrate the birthday of Brown’s character Frank.

The 72-year-old Brown wanted to tell a story about his generation, sparked by an overseas Christmas he had spent with a close bunch of mates.

“You know with friends you’re always laughing and joking and you talk a bit about what’s going on or how are your kids or whatever,” he tells Stellar.

This time that holiday bonhomie had a worrying undertone. “I came away knowing that everyone — everyone — was dealing with something,” recalls Brown. “All the blokes were dealing with something.”

One mate had been a lifelong alcoholic and was still dealing with the trauma that brought his family. Another had lost his job, and with it his identity. Another had just sold the company that had been his life.

Explains Brown, “And now he’s bumping into walls and didn’t know which way was up.” He had gone on antidepressants.

Then there was Brown, the seeming constant of the past four decades of Australian film and TV. Surely such a totem couldn’t topple, too? Yet he had also been dealing with personal chaos, and did not know how to mend himself.

While filming the romantic comedy Along Came Polly in the US more than 15 years ago, Brown was rushed into intensive care with a serious blood infection.

It knocked him around as much mentally as physically, although he didn’t know it at the time. For years after, his anxiety about another possible episode ballooned.

He was gripped by nervous thoughts about the permutations, particularly if he wasn’t near another hospital that could save his life, as happened in America.

“And, of course, once you start to build up anxiety, other things can trigger it that you get worried about,” he says. “But I didn’t know what was going on. Something was happening to me.”

Physically, he was addled yet doctors couldn’t diagnose anything concrete. He was prescribed antibiotics to no effect.

“I just got to the end of my tether and thought it just can’t be some virus or disease thing, it can’t be,” he recalls.

A chance observation by his actor daughter Matilda triggered a breakthrough. She told him he sounded like she did when auditioning, racked with nerves.

So Brown did what few Aussie blokes have the wherewithal to do: he asked his GP if he could see a psychologist.

After about four sessions — or “eps” (episodes), as Brown unwittingly refers to them — a diagnosis arrived. He had crippling anxiety.

“But once you know what something is, it doesn’t just stop because it’s sitting in there and it’s taken hold,” notes Brown. “It’s about making it let go and then just elbowing it so that voice can’t get in there anymore.”

At that recent Christmas, Brown was dealing with it, past the fragile stage and lucid enough to realise something — namely, he says, “We were all struggling. [And] I said to Rachel, I reckon there’s a film in this age group where people think, ‘Oh... nothing could be going wrong. It must be easy travelling.’ But it isn’t easy. They’re actually travelling with some struggles.”

Brown also felt his cohorts weren’t being looked after onscreen. People still ask him when he’ll reunite with Sam Neill on another series of the ABC show Old School that aired in a single season in 2014.

“There’s nothing out there for us,” they tell him. “When’s someone going to talk about us [in a way] that we can relate to?”

“Loneliness, relationships, break-ups, their parents, Alzheimer’s, all these sort of things are really painful,” says Brown.

“And you can go, ‘Well, it’s not as painful as being in a refugee camp.’ No, it’s not. And that’s a story that needs to be told. But let’s not think things aren’t going on with all of us.”

MORE STELLAR:

Remembering John F. Kennedy Jnr and Carolyn Bessette

David Campbell: ‘Could my son be Princess Diana?’

Palm Beach’s middle- to upper-class affluence is a rare sight in Australian movies, which tend towards suburban realism or outlandish comedy. Brown pre-empts any criticism its comfort is a negative.

“We haven’t been doing audience-friendly movies, you might say, and by that I mean making people cry, making them laugh and making them feel that it’s OK and we can deal with stuff,” he says. “That’s part of life, the struggle, reminding us that our humanity keeps us all together.”

And it’s not the only story to tell, says an actor who hasn’t ever confined himself to a niche.

He notes, with a little pride, his recent output has included “a suburban, intercultural piece” (Foxtel’s 2017 TV-movie Australia Day), last year’s Indigenous historical film Sweet Country, Stan’s Logie-winning TV mystery series Bloom and the upcoming SBS drama Hungry Ghosts, which is set in Melbourne’s Vietnamese community.

“I look at all that and think, ‘This is Australia.’”

Asked why he keeps pushing and searching to tell Australian stories, Brown replies with a smile, “Other people will determine my retirement, not me. But while they’re silly enough to ask me, I’m gonna be doing it.

“And while I’m silly enough to think up ideas, I’m going to be trying to persuade people to go with me.”

Palm Beach is in cinemas nationwide from Thursday, August 8.