Ten weeks after my baby was born, everything changed

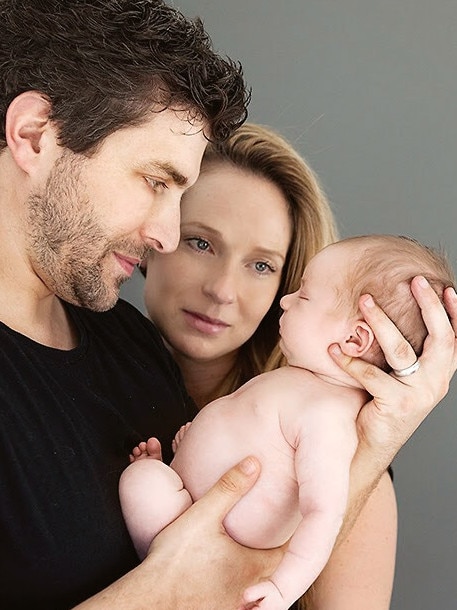

The two months after Rachael Casella’s daughter Mackenzie was born were the happiest of her life. But then Mackenzie was diagnosed with a terminal illness.

- JLo: ‘The bodies we see have changed — and I helped’

- Michelle Leslie: ‘I’ve been judged by everyone in Australia’

It’s been a year since Rachael and Jonny Casella lost their seven-month-old daughter Mackenzie. The grief is still raw, but Mackenzie’s Mission has given them new hope.

People shy away from speaking about Mackenzie because they are scared it’s going to bring up emotions for us. But by bringing up Mackenzie, we’re never going to be reminded about her because we don’t, for one single second, forget about her.

Before Mackenzie was conceived, we had a miscarriage. It was very hard, but we tried again, and had Kenzie. She was the most perfect, beautiful little baby.

Jonny and I had eight weeks off work together with our baby. Those eight weeks were the happiest of my life. Then at 10 weeks, everything changed.

MORE STELLAR:

Why you won’t ever see Norah Jones singing at a wedding

Ben Lucas: ‘I thought I’d been stood up!’

We took Kenzie to see a paediatrician because one of the lactation consultants at the local hospital had said she wasn’t moving the right way, and the local doctor seemed to think something was wrong, too. We hoped they were wrong.

Within two minutes of looking at her the paediatrician said, “I’m 95 per cent sure she has spinal muscular atrophy [SMA].” We didn’t know what SMA was, so we said, “What’s the plan? Is it physio?” And he shook his head and said, “No. It’s a terminal illness.”

I don’t think anyone can ever describe adequately in words what it’s like to be told your 10-week-old baby has a terminal illness. Jonny and I couldn’t speak.

The next day we saw a specialist and she confirmed the paediatrician was right. We were told it was a recessive genetic disorder, which means that Jonny and I were carriers. There was a lot of heartache. We’d given this to her.

They started talking to us about the risk to future babies and I’m just sitting there going, “Are you trying to tell me that my baby is going to die and we won’t be able to have more kids?”

One in 20 children are born with a genetic defect. Dozens of genetic tests are available in Australia, so we wondered why we weren’t told about it. GPs are known to only refer people for genetic carrier testing if they have a particular cultural background or family history of it. But four out of five children born with a genetic disorder have no family history.

When she was seven months old, Kenzie got very sick. We were in ICU and she went up and down. Then we got pulled into a little room and told she was probably not going to come home. We all laid in bed together and had some time.

And then she was gone.

I don’t know how we walked out of that room. I don’t know how when you experience that pain you don’t die as well. You don’t understand how people are still sunbaking on the beach or getting coffees or fighting about petty things. Can’t the rest of the world feel something significant has happened?

I’d written a letter about Mackenzie and the importance of genetic testing to members of Parliament. We were invited to attend the Budget in May of this year, and were told there would be a $500 million genomics project and the first pilot program would be Mackenzie’s Mission, which will research genetic carrier testing.

We’re not the first people to have lost a baby to a genetic disorder. Mackenzie’s Mission represents something for all of the kids who should still be here.

For more about Mackenzie’s life and mission, visit mylifeoflove.com.