Sex sells: From Magic Mike to Bridgerton it’s all about the female viewer

The Australian cast of Magic Mike Live open up about exploring what women really want and feeling vulnerable onstage.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Ask a man what he thinks women fantasise about and he’ll doubtless come up with a predictable list: firefighters, soldiers, bushrangers, cops. And that’s exactly what the opening scene of Magic Mike Live dishes up as a troupe of (ahem) very fit men pose and gyrate around the stage as if ordered and dressed from the Department of Clichés.

A male MC continues with the time-worn script, telling an audience of “eager beavers” that he and his beefy mates are going to make it “magical in your vagical”.

A few minutes in, however, and suddenly a woman strides on to the stage. She doesn’t want any of these dated stereotypes. As she explains, she has more subtle fantasies: the barista around the corner; a slightly dirty muso; a guy with a great smile; someone who laughs at her jokes; a hot guy in jeans and T-shirt. Or, as she points out to the 600-strong audience of mostly women, “someone I can take home to meet my mum”.

And so it is that with a female MC at the helm, the show – currently playing in Sydney but set to move to Melbourne then Brisbane – subverts the old-style stripper revue and delivers not just hunky half-dressed blokes, but also a funny and joyous insight into women’s predilections and desires.

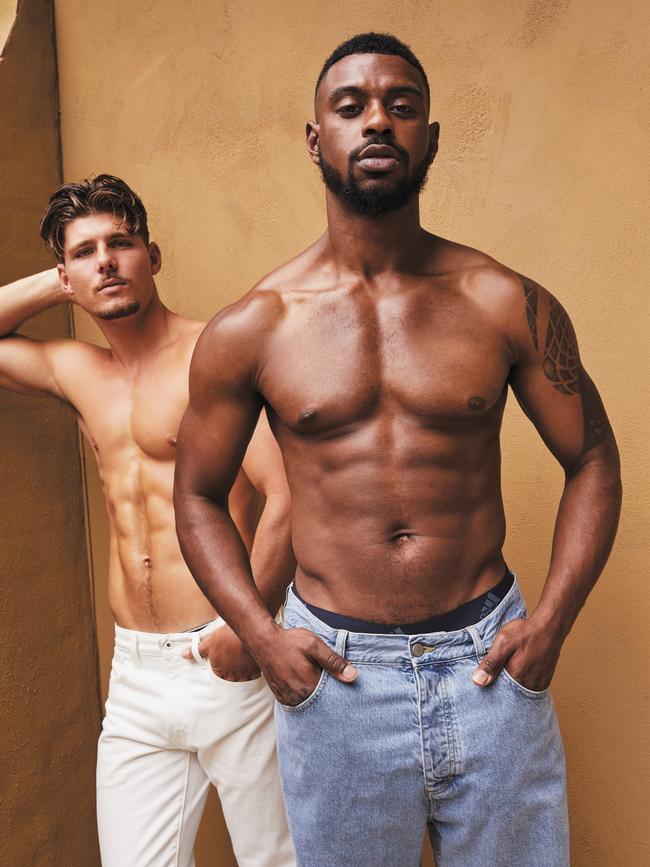

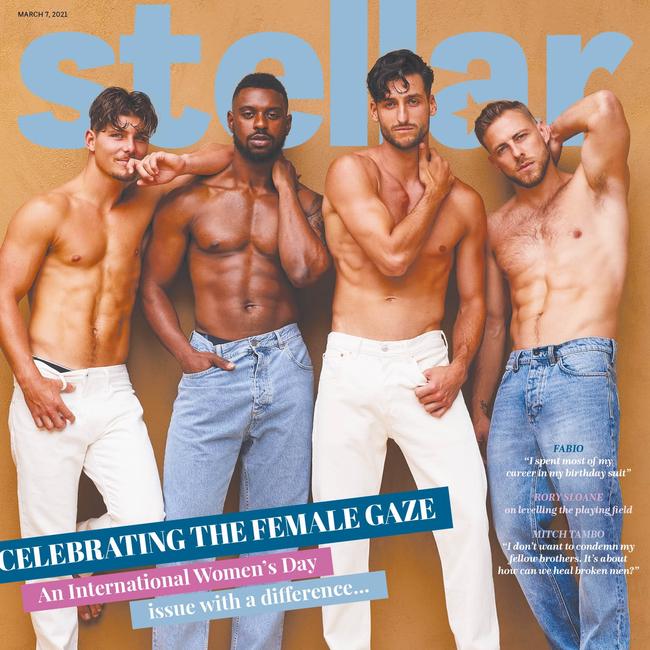

Taking four of those muscled men from stage to page is not how we’d typically celebrate International Women’s Day. There will be some who question what right they have to occupy such prime publishing real estate on a day that traditionally honours and amplifies the achievements of women.

But here at Stellar we already have a reputation as a mouthpiece for women’s stories.

Each week through the reflections of notable women, we address the subjects and themes that unite us: work, pay, pregnancy, motherhood, miscarriage, menopause, abortion, addiction… Of course, there are still battles to be won and frontiers to navigate – among them equal pay, domestic violence, abortion rights and a quietly emerging global concern that the pandemic has set women back decades as they’ve become multi-purposed at home.

But today we’re being both provocative and powerful (and a little bit playful) in our recognition of something many may have never heard of: the female gaze.

“Female gays?” enquired one confused bloke who could not reconcile how our cover shoot might appeal to the demographic. Without getting too academic about it, the “female gaze” simply recognises a woman’s viewpoint in all forms of entertainment.

It’s a flipping of the script in response to theatre, art, dance, film and television historically being directed both through the eyes and for the eyes of men.

The “male gaze”, a term coined by art critic John Berger but brought to prominence by film theorist Laura Mulvey in the 1970s, refers to the depicting of women in these art forms from a masculine, heterosexual perspective in a manner that empowers those men and objectifies women.

In essence, women were both spectacle and receptacle, characterised – as Mulvey pointed out – by their “to-be-looked-at-ness”.

You’d think, then, that the “female gaze” is simply a reversal of this dominance, but those spearheading this new paradigm see it as far more nuanced. It’s not just about women looking at men. Rather, female directors and cinematographers argue the female gaze allows the audience to feel what women see and experience.

Some regard it as exploring a woman’s emotions and sensuality, as showcased so notably in the Netflix hit Bridgerton. Others, like acclaimed writer and actor Phoebe Waller-Bridge, invoke the female gaze via narration, direct audience address and fantasy sequences in shows such as Fleabag and Killing Eve, while some herald it as a new form of respect; an attempt to empathise rather than objectify.

Certainly, that’s what actor Channing Tatum was trying to achieve when he turned Magic Mike from a film into a stage show.

“I wanted to create a space where men really listened to women,” he has observed. “Where all women could experience a place where just being themselves would be enough for every man in the room. I wanted to take a type of entertainment that has not evolved at all since the late ’70s and reimagine it for the world we live in right now – to provocatively jump-start the conversation about what it is that women really want from the men in their lives.”

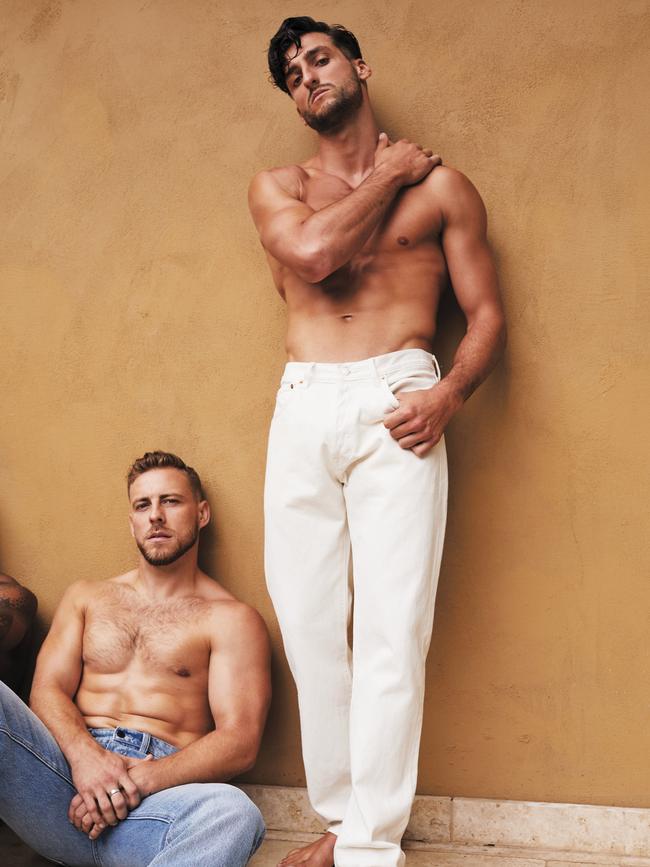

To that end, the men in Magic Mike Live weren’t simply chosen for their physiques or their dance skills. As they explain to Stellar, the audition process included interacting and dancing with ordinary women, socialising in a bar and talking about their relationship with their mums and other female role models.

Ned Zaina, 25, from Melbourne, relished the fresh approach as a means of redrawing what he calls “the lines of respect”.

As he says: “They wanted to hire nice men. You could be the best dancer in the world but if you haven’t got the right attitude to women then you could be the bad egg that spoils a show like this.”

It’s a far cry from Manpower, the country’s first male strip show, which began in the ’80s in a small nightclub in the Gold Coast, famously featured Jamie Durie and promoted itself as being “100% Australian beef”. As Magic Mike Live tap dancer Sam Marks points out, even the name of the touring troupe left no doubt as to who was in charge: Man. Power.

According to the 31-year-old Queenslander, it’s a different vibe in 2021. “We asked women what makes them feel special, what makes them feel loved and excited, and we created the show around that.”

Those who see the live show will observe a sharing and swapping of power, particularly in an athletic simulated sex scene between a male and female dancer that takes place in a pool with water pouring from the ceiling. There’s a similar transfer of power between performer and audience, which is what won over journalist and former newsreader Jacinta Tynan when she saw the show.

As she tells Stellar: “When it comes to the female gaze, the pendulum needed to swing, but it raises questions and I wasn’t sure I’d be comfortable at a show that objectified men.”

She regards Magic Mike Live as more of a “thought-provoking collaboration” that uses irony, humour and clever choreography to celebrate sex, while also delivering a strong message that when it comes to intimacy, both parties need to give permission.

The flipping of the gaze has long been a source of curiosity and study for model-turned-author Tara Moss, who addresses the issue in her social analysis and memoir The Fictional Woman.

“Perhaps it’s time,” she observes, “for the ‘beautiful man’ to be permitted by the producers of our mainstream visual culture to show himself – to loosen his tie, look us seductively in the eyes, and admit that he is human and he wants to be wanted, too, and for more than his brute strength or his bank book.”

For the Magic Mike Live dancers, moving into this territory and being the subject of the female gaze elicits complex emotions. Aaron Theodore Cooke, 26, says he and his co-stars feel like “people first, performers second” while even at 22, Blake Varga understands that central to his role is an ability to make women “feel noticed and appreciated”.

But that doesn’t mean these men don’t feel vulnerable at times. Marks says he can feel both powerful and powerless. “When you’re standing on stage in next to nothing and you’ve got 600 pairs of eyes staring at you, it can leave you feeling objectified. I’ve relinquished power so I do feel vulnerable and that gives me a greater understanding of how, traditionally, women would have felt that vulnerability.”

Zaina reveals how, despite COVID restrictions, women in the audience occasionally try to grab or touch him and his colleagues. Some scream out offensive comments or reject one performer dancing in front of them and insist on being entertained by another.

“You have to come at it with a positive outlook, but sometimes it does get the better of you and you feel like a piece of meat,” he says.

“Obviously, we’ll never understand what it’s like to be a woman, but we are in this position where we are cat-called or yelled at or treated like an object. We’ve been put in a woman’s shoes and you can see it could be uncomfortable.”

Amy Ingram, who plays the female MC, says the show highlights the breadth and complexity of women’s desire.

“It allows women to sit in the gaze and really enjoy it. Traditionally the male revue has been borderline cringe-worthy, with no real acknowledgement of what women want to experience. The show highlights that women also have desires but not everything for us is sexual. Sometimes we do just want sex and to be turned on, but other times we just want to feel appreciated.”

It’s precisely this nuance and diversity around women’s desire that is being explored in contemporary film and television, particularly as the number of female directors continue to grow.

The highly regarded Celluloid Ceiling study by San Diego State University found that women made up 16 per cent of directors working on the top-100 grossing Hollywood movies in 2020 (up from 12 per cent in 2019 and 4 per cent in 2018) while producers Shonda Rimes (Bridgerton, Grey’s Anatomy) and Australian Bruna Papandrea (Gone Girl, Big Little Lies, The Undoing, Penguin Bloom) are being heralded for their creativity in telling women’s stories.

Along with more women taking the lead, there’s a growing move to choreograph sex scenes not just to preserve the safety of actors, but also to bring a woman’s perspective to the storytelling.

Sheree Folkson, one of the directors on Bridgerton, tells Stellar that she wanted love rather than sex to be the focus when the lead character, played by Phoebe Dynevor, loses her virginity.

“Once they finally kiss and start getting to sexually know each other, I wanted the audience to feel it very much from Phoebe’s point of view. I spent a long time filming in close-ups the clothes coming off, and then when editing it we focused on her reactions to what was happening much more than his: her surprise, delight, excitement and arousal at this wonderful new experience.”

Folkson continues: “I asked the actors to keep looking at each other in the eyes, so the audience could share in that wonderful intimacy they were experiencing as two people in love. For me, that was more important than body parts.”

While choreography is central to Magic Mike Live, it never takes itself too seriously, shifting from sexy and seductive to ironic and comical. When we see a woman serenaded while sitting on top of a piano, Ingram, as MC, pithily points out that this has happened to zero women ever in real life. “Humour is such a big part of it; men are surprised we can laugh at something and still be turned on,” she tells Stellar.

“This doesn’t need to be a serious thing. You can appreciate and enjoy the male physique without it being a source of shame.”