Sam Dastyari: ‘I would love to stop hating myself’

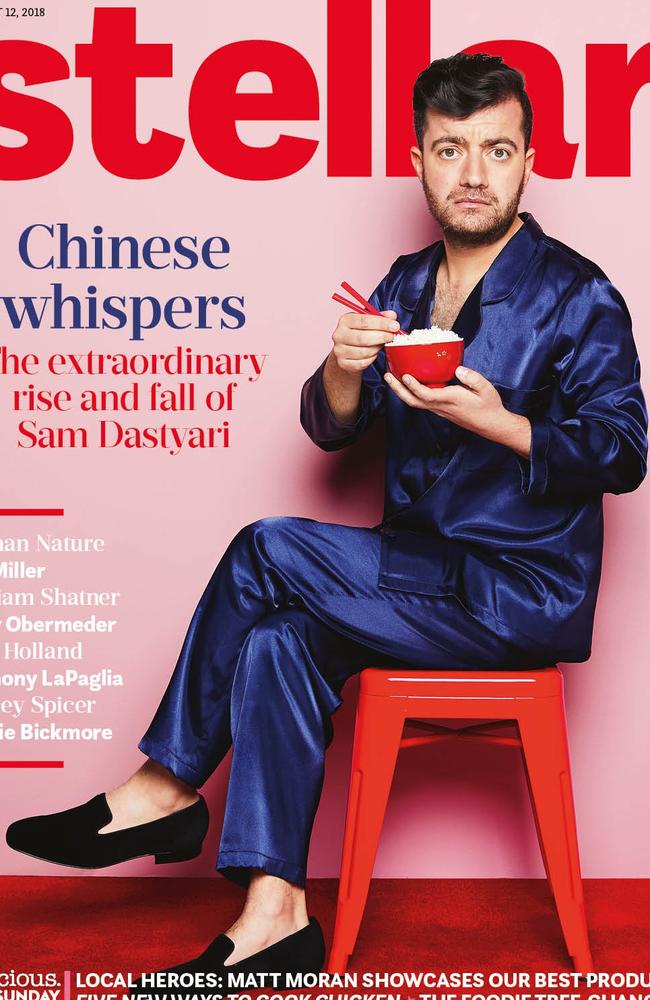

SHAMED politician Sam Dastyari opens up for the first time about the scandal that cost him his career and the demons that plagued him in the aftermath.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT’S three o’clock in the morning, the time of day that blues songs are written about and when nothing good ever happens, and a dark-haired 30-something is sitting in a casino hitting the bottle.

Or, more specifically, the third bottle. He’s on meds, he’s boozing most nights, he’s lost the only thing he ever wanted and he’s out partying with anyone who’ll have him — a dangerous option for a man who is never short of mates.

Just a few months earlier this short, slight, doe-eyed and baby-faced drunk was one of the most powerful men in Australia: the right-hand man to the probable next prime minister, the youngest man to have controlled the Labor Party’s levers of power, and maybe even the future premier of the nation’s largest state.

MORE STELLAR:

How Sam Frost proved the critics wrong

Meet the new kid on Kyal and Kara’s Block

But that is all over now. That dream is shot and its shattered pieces are barely strung together by a febrile mixture of prescription drugs, liquor and self-loathing.

Oh, and possibly the greatest political mind of his generation. Ladies and gentlemen, meet Sam Dastyari.

“I’ve done every drug under the sun, and they were all beaten by the euphoria you get from that relief.”

So says Dastyari as he sits down for an exclusive interview with Stellar, remembering the good times.

But he’s not talking about the time he was the youngest-ever boss of NSW Labor, nor the youngest senator in the federal caucus. He’s talking about the time he was forced to quit the Parliament in disgrace.

It was late 2017 and Dastyari was already on a good behaviour bond after asking a Chinese company to pay his travel expenses, a relatively paltry $1670 and 82 cents. Dastyari joked at the time that he was a bit of a tight-arse.

“I just didn’t think twice about it,” he admits now.

There is a school of thought along the lines that Liberal politicians are the best of a bad lot, while Labor politicians are the worst of a good lot.

If someone from a blue-blooded family becomes a politician, it’s a public service. They forsake their millions from the corporate world for the sake of the greater good. For them a six-figure salary is basically volunteer work.

But for anyone from a poorer background, a job in politics isn’t a pay cut, it’s a bonanza. Politics is their ticket to a better life. As the ALP titan Neville Wran once said: “That’s what being in the working class is all about — how to get out of it.”

And Dastyari was nothing if not a man on the make. He was born in Iran and came to Australia at the age of four in January 1988, that most celebratory year at the apex of the Hawke-Keating government. He was raised in Western Sydney, joined the ALP at 16 years of age and went on to become president of Young Labor.

Soon he was a key operative at the NSW Labor HQ in Sussex Street, Sydney, in the heart of Chinatown. And while Melbourne has always been the spiritual home of Labor’s left-wing union base, Sydney has always been the cynical home of Labor’s right-wing party peak. If Melbourne was Labor’s heart, Sydney was its brain.

And no-one was brainier than Dastyari. Even when he was a mere state organiser he could rattle off the key demographics and hot-button issues in every marginal electorate, down to each voting booth.

Then at the age of just 26 he became general secretary, a role that includes keeping the peace at Labor conference by ensuring the right always wins while the left feels pure, fixing feral preselection battles, dividing up precious campaign resources, crafting perfectly targeted attack ads and running an endless program of marginal seat polling and qualitative focus groups to keep MPs in line.

But the most important and dangerous thing the gen sec does is raise money from anywhere they can. And Dastyari was incredibly good at that.

“I think my mistake is that I went into Parliament and kept behaving like the general secretary of the Labor Party running Sussex Street, and that meant managing relationships with party donors. And that was an incredibly stupid thing to be doing,” he says.

“I should have walked away. I should have cut off all those links. You cannot be a parliamentarian and be behaving like the back-door party operator that I was.”

In other words, when your job is to constantly get money out of people, sometimes you forget to stop doing it. And when he got stuck with a bill he didn’t like, he just instinctively got someone else to pay for it.

“I shouldn’t have been the party bagman when I was a serving Australian senator,” he admits now in what would surely be seen by many as an understatement — to put it mildly.

Having had to step down from the front bench, he was on the road to redemption when it emerged he had also met with the owner of that company to tell him he was under surveillance by security agencies.

Dastyari says he only met with him to tell him they couldn’t be friends anymore because he was suspected of being a spy. In Dastyari’s version he was cutting him loose; in the national security version he was tipping him off.

Either way, it didn’t matter. This was his second strike. And there were also his bizarre statements supporting China’s territorial claims. That was three, and Dastyari was out.

In the lead-up to his emotional — and now infamous — press conference last December where he announced he was resigning from the Australian Senate, after the controversy over his connections to Chinese donors had made his position untenable, he called Bill Shorten, the man he had helped make Labor leader.

“I think my exact words were: ‘I’m completely f*cked, aren’t I?’” Dastyari tells Stellar.

Shorten said: “Mate, you were probably f*cked about 48 hours ago.”

For Dastyari, politics was a drug. And the next morning he quit it forever.

THE FIVE STAGES OF DISGRACE

Scandal is like a disease. It attacks a person, infects them, and then condemns them to isolation. At first it seems like it’s happening around you, but it quickly seeps through the skin.

“Going through that horrible period definitely changes you,” says Dastyari. “It makes you aware of pain.”

As he picks apart his psyche for Stellar, it unfolds there are precisely five stages of that pain.

EUPHORIA

First came the relief. He had been stalked and stoned for so long and on such a grand stage, that he was simply overjoyed it was over. “The moment I resigned from Parliament was probably the best I’ve ever felt in my life,” he says. “Just the euphoria of relief.”

This is also the time that everyone rallies. The phone calls flood in. There is even a kind of Brotherhood Of The Damned. Others who have been minced by the outrage grinder resurface and reach out. Matty Johns, who Dastyari had never met before, took him out to dinner to make sure he was OK. Kyle Sandilands, the king of scandal himself, offered him a lifeline on his top-rating radio show.

“I think I’m the only person in Australia who was taken out of depression by Kyle Sandilands and not put in it,” Dastyari observes.

“It’s like being at your own wake,” he adds cheerfully. “And then two weeks later, people get on with their own lives and the calls kind of stop, and that for me was when that darkness really hit.”

DEPRESSION

The darkness was deep. “I spent six days where I didn’t leave my bedroom.”

The sheer mass of all he had lost was too much for his mind to absorb, but worse still was the knowledge that he had lost it himself, that there was no-one else to blame. And so he soon started thinking the darkest thought of all.

“There were certainly nights where your logic goes so out the door, that you suddenly start thinking things like: ‘Well, the people who love me would be better off if I wasn’t here anymore...’”

Dastyari never got to the point of actually planning suicide, but he certainly contemplated it. He needed help.

Eventually Dastyari went to see a doctor who prescribed him some hardcore antidepressants. But he also gave him a warning: the drugs would only treat the symptoms of his sorrow. The cause he would have to sort out himself.

Still, it wasn’t all bad news. The doctor told him: “The fact that you’ve come here and told me you’re depressed is the only sign I’ve got that you’re not a sociopath.”

Dastyari laughs at this. It’s almost as though he is genuinely relieved.

DESTRUCTION

Thanks to the meds, Dastyari was now able to leave the house. Unfortunately, thanks to the meds, Dastyari was now able to leave the house. He soon found himself out on the booze most nights with anyone who was around. He would typically go through two or three bottles of wine, plus beers and shots.

“The breaking point for me was it was 3am, I’m at the casino — because it’s Sydney and everything else is closed — and I’m drinking heavily for like the third or fourth night in a row and I go: ‘Something’s gotta change.’”

Being Dastyari, that meant everything changed. In an instant he gave up the prescription drugs, the booze and even food.

For 15 days he didn’t eat and survived on literally nothing but water. The first 72-hours of withdrawal, he says, were the worst he has ever felt. Then, after that, came a kind of high.

ACCEPTANCE

And that brings us to where we are now as Dastyari sits down with Stellar, nursing a cup of tea. He is eating again and even has the occasional drink.

While only a couple of months earlier he seemed almost physically broken, he looks good — and is back on the hustle, back in the game. And his latest obsession is disgrace itself. He is like a doctor searching for the cure to his own disease.

And so he has come up with a whole TV show called Disgrace! devoted to asking the question: How does someone like Monica Lewinsky ever live a normal life again? Or Schapelle Corby? Or Sam Dastyari?

He even calls the show his “therapy”. In the end the only way he could deal with his personal trauma was to turn it into a political problem for him to solve, and do so once more under the public’s glare. Even after being destroyed by politics and the media, he is still addicted to both.

“For me, maybe this is the only way I can deal with it — the only way I can try to understand it,” he reflects.

His wife has a different theory. She told him, “I’m not quite sure of what a midlife crisis looks like, but it probably looks something like this.”

FORGIVENESS

It takes nine months for a human being to be born and it has now taken nearly that long for Dastyari to be reborn. But rebirth doesn’t always mean redemption.

Indeed, the worst part of his trials isn’t the public vitriol or national shame — it’s himself. Even as he struggles to understand and accept what he’s done, he still can’t forgive himself for doing it.

“I’m not there,” he says.

Yet he refuses to blame anyone else for his fate or allow himself the brutal absolution of suicide. He describes both options as “escapism”. Instead he insists on walking the hard narrow road down the middle, carrying his cross alone.

“I don’t want pity, I don’t want forgiveness, I don’t want acceptance,” Dastyari says. “But I would love to stop hating myself.”

Disgrace! premieres 8.30pm, Sunday August 19, on Network Ten.

Lifeline: 13 11 14