Orgies, spies and betrayal: The true story behind the film Allied

CINEMAS will be dominated this summer by a WWII tale of love behind enemy lines. But what’s the real story that inspired the film?

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IT’S a story worthy of a movie in itself. A 21-year-old Englishman is travelling in the US, uncertain what his future holds and keen to see the world.

“I was doing various odd jobs, working my way around the States,” Steven Knight, now a screenwriter, tells Stellar. “I was in Arkansas, lodging with an Englishwoman who was a GI bride — she’d come to the States after World War II, having married a US soldier.”

It was a hot night, he recalls, and the landlady and lodger went out to the backyard to cool off. “And she told me the story of her brother, who was in the Special Operations Executive [a branch of the British Army formed to carry out sabotage and espionage behind enemy lines]. He met a female French SOE operative, they fell in love and got permission to go back to England to marry. So they did, and they had a child. He left home one morning, part of a happy family, and kissed his wife goodbye. When he got to work, his superiors told him his wife was a spy working for the Germans. He was handed a gun and was told he had to shoot her to prove his loyalty.”

Unsurprisingly, this harrowing story stuck in young Knight’s mind as he returned to the UK and embarked on a career in TV writing. But there it remained, unwritten, for 30 years — until four years ago, when his career had blossomed to the point of working with Brad Pitt. One day, as the two were chatting, Knight told Pitt the story, and Pitt’s reaction (“He had chills,” says Knight) convinced him to finally turn it into a screenplay, which he titled Allied.

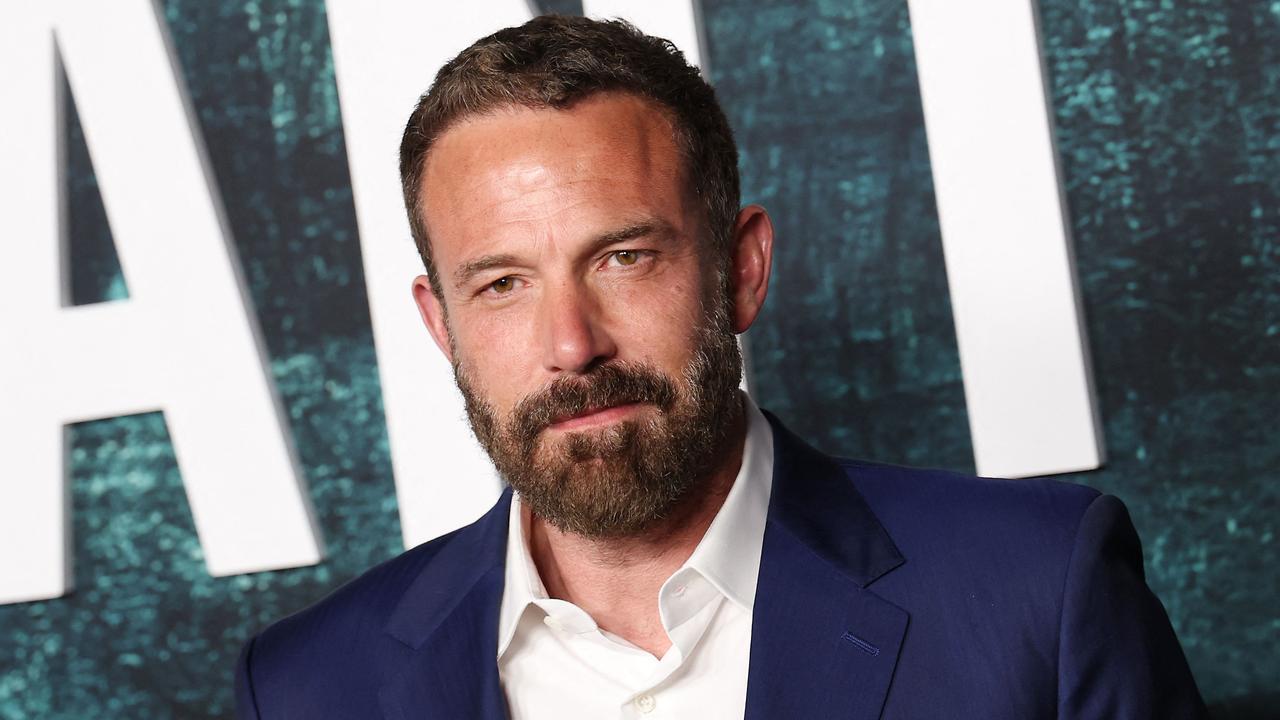

Starring Pitt and Marion Cotillard, the result is a big-budget wartime romance opening in Australia later this month. As they say, the rest is history … But how much history is in the film?

“My research suggested the Germans didn’t use female operatives and the Germans didn’t penetrate British security,” admits Knight. “However, I was 21; I wasn’t a writer — why would [the landlady] make it up? She was emotional telling me the story, it was a family skeleton in the cupboard, so I believe it really happened.”

Knight didn’t try to track the woman down, and believes she has since died. But he did do his homework. “I read every book on the SOE,” says Knight. “I particularly read first-hand accounts, because I think history is best consumed first-hand — historians tend to tidy it up a bit. But the SOE story is pretty well documented. The agents did the most amazing things; they were incredibly courageous and often went into the field thinking they weren’t going to come back. Often they didn’t.”

The SOE started as a ragtag, barely legitimate operation run by Major General Colin Gubbins on thoroughly non-traditional lines. It also revolutionised the British Army and was key to the Allies winning the war, says historian Giles Milton, author of The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare: Churchill’s Mavericks Plotting Hitler’s Defeat.

“The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare” was Churchill’s nickname for the unit that was roundly despised by the upright, uptight British Army, which worked on the principles of fair play, honour and decency. These new tactics of sabotage, street fighting and silent assassination were symptomatic of a new world order, in which, says Milton, “Recruits had to unlearn the rules of cricket to win the war at all costs.”

Churchill quickly grasped the value of the SOE’s missions into enemy territory, during which they bombed targets, gathered intelligence, liaised with the French Resistance and assassinated Nazis. He grandiloquently commanded them to “set Europe ablaze”.

The SOE’s exploits — secret saboteurs equipped with codenames, poison pills and briefcase bombs — have inspired countless fictional tales. Milton describes one raid in which the SOE liberated three enemy ships from a Nigerian harbour, while in-the-know local officials regaled their German commanders and crew with fine food and strong drink. Elated by their victory, the UK agents ran a Jolly Roger up their ship’s mast.

“One of my favourite characters,” says Milton, “is Cecil Clarke — he went from being a caravan engineer to designing some of the most lethal weapons in the Second World War.”

One such weapon Clarke created in his workshop was a lethally accurate, technologically advanced bomb he built from a Woolworths’ washing-up bowl, an aniseed ball, a condom and some explosive charge. His limpet mine sank countless ships during the war.

The colourful characters working in London were matched by romantic tales of high courage and derring-do abroad. “These were people who had a smattering of French,” explains Knight. “They were 21 or 22, and were sent to a training school in Scotland, where they learnt a hundred ways to kill an opponent quickly. Then they were given false ID and some currency and dropped behind enemy lines. In some cases they were given false information, so if they were captured and tortured, they wouldn’t hinder the war effort. It was very ruthless.”

But is the central conceit of Allied — the idea of a “standard operating procedure for intimate betrayal” — realistic?

Milton, who for two years delved into military archives and documents stored by SOE agents’ relatives to write his book, isn’t convinced. “I think that’s complete nonsense,” he tells Stellar. “It’s certainly a very interesting and colourful fantasy, but I’m not sure this would have ever taken place. The idea of treachery and betrayal within the SOE, this world of espionage and double-dealing, is a very potent story because it did happen — the archives are filled with agents being compromised. So, in that sense, the film has tapped into something that is true, but I think Hollywood has taken the basis of the story and piled on a lot of colour to make it an entertaining film.”

Often, though, the most outlandish incidents were plain truth. “The most extraordinary stories do crop up,” says Milton. “Sometimes I’m in the archives and think, ‘I really can’t believe that — if I write that in the book, will anyone actually believe it’s true?’”

Knight ran into the same problem. A notable party scene at Pitt and Cotillard’s London house, which is riotously full of drunken soldiers, drug use and illicit sex, and only winds up after the house suffers a near miss in an air raid, was actually toned down from a true story.

“I read about Hampstead in the Second World War — it was an incredibly hedonistic, licentious place, because with bombs dropping, people didn’t care,” he says. “I read a first-hand account of a fireman who was called to an incendiary bombing. He went into a house to find the bomb and put it out, and in the house there was an orgy going on. And even though there were bombs going off and firemen rushing around, the orgy didn’t stop. We think of Londoners having that ‘Keep calm and carry on’ spirit, but there was a bit more to it!”

Still, those everyday Londoners were heroes, believes Knight. And so were the SOE agents working in secrecy to ensure London — and Londoners — could endure. “If Allied leads people to look at the work of the SOE in the Second World War, that’s fantastic,” says Knight. “Because they’re unsung heroes who really did risk their lives every day.”

Allied is in cinemas on December 26.