Michael J Fox shares how Parkinsons battle may end career in new memoir

After 40 years of fame, Michael J Fox reveals why his ongoing battle with Parkinsons has made him uncastable and could signal the end of his career.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

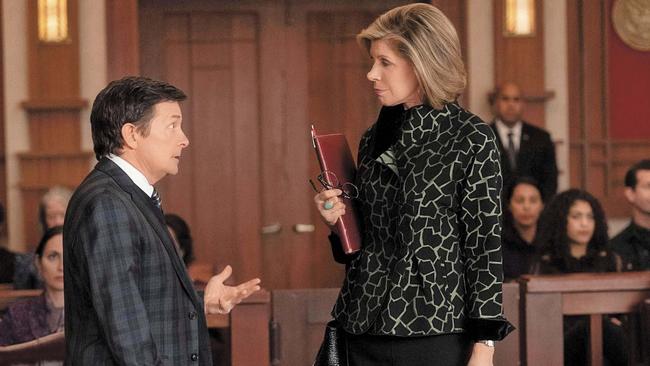

As if I’d never gone away, The Good Wife has me back for a few episodes during their final season. It is a tonic. Over the next couple of years, I accept two guest shots on other network shows that are not as satisfying. These are the last acting roles I’ve done, and most likely the last I will do.

I feel no sadness in making this prediction. Like [wife] Tracy said after we sold our house in the country, the one the kids had grown up in: “This house owes us nothing.” I feel the same way about my second act, and golf, too, for that matter. They owe me nothing.

They both took me further than I expected, to places I may never visit again.

There is a variable that hadn’t been present in the Scrubs to Rescue Me to The Good Wife run. In those shows, I had figured out a way to incorporate my extraneous movement, my spasticity, even my rigidity.

I didn’t have to move much to play any of those characters. A chair, a cane, a desk to lean on. I could get around the set without calling attention to my limitations.

But not being able to speak reliably is a game-breaker for an actor. Difficulty in forming words is one problem, the other is remembering the words I am meant to say. Previously in my career I had no problem with line memorisation.

In fact, as I’ve said about the days of Family Ties, I enjoyed a near-photographic memory. But recently that changed. It’s a different story on these last two dramas, in which I play lawyers. “Legalese” is difficult to learn and speak, never mind understanding what the hell I’m saying.

First, I agree to a five-episode arc in Designated Survivor, playing a white-shoe Washington, DC, attorney, representing the cabinet as they try to remove the president of the United States via the Twenty-Fifth Amendment.

For me, “survivor” is the key word. While this role is challenging and fun creatively, it is a self-inflicted assault on my brain and body. Not only do I endure a perfect storm of symptoms, but I have to film during February and March in Toronto. Snow and ice, and long distances to walk between sets in the enormous warehouse studio.

I don’t know it yet, but I am a little more than a month away from surgery on my spine.

In the complicated plot, my character is both ally and adversary of the president, played by Kiefer Sutherland, an old friend of mine. We worked together in the ’80s on Bright Lights, Big City. A terrific guy, at once folksy and urbane, Kiefer welcomes me on the set, a happy reunion.

As I’d remembered, Kiefer likes to work fast, briskly, picking up on other actors’ cues, with very little air between the lines. Although I enjoy this quick and snappy style, I just can’t oblige.

“Whereas in the party of the second part…” leads immediately into “habeas corpus…” and then right into “posse comitatus…” I’m lost, and have to start again. I can’t get through a scene without having to stop, and with confusion and embarrassment, call out to the script supervisor: “Line, please.”

I had enjoyed this formal lexicon in the past. I nailed it on Boston Legal and The Good Wife. I loved the musicality of it, and I had no problem in rolling out the legalese. But this is different.

I know the editor will save my ass, and he does. But it has not been a pleasant experience. I no longer have the facility, and the thrill is gone.

On The Good Fight, a spin-off of The Good Wife, I am Louis Canning again, so that familiarity is helpful. But in the few years since I last embodied the character, much has changed with the show, and with me.

The production is leaner and on a tighter budget, with a shorter production schedule and more scenes to film in a day. They can’t allow me the rest and recuperation between scenes and film days that had been afforded by the larger mother show.

The upshot is that I play three six-page scenes in the course of a day, covered in such a way that I have to perform all three scenes at once, 18 pages at a time, instead of shooting the scenes individually.

It crushes me.

A reference to [Quentin] Tarantino’s Once Upon A Time In Hollywood: Leonardo DiCaprio, playing a cowboy actor who’s seen better days, keeps screwing up his lines while doing a guest shot on a popular TV Western.

Furious at himself over his chronic inability to remember and deliver the dialogue (we’ve seen him going over and over the script in scenes prior), he retreats to his boxy dressing-room trailer, takes a stance in front of the mirror, and berates himself viciously over his abject failure.

I feel his pain. I’ve obviously been there. But weighed against everything else in my life, I don’t find it worthy of self-excoriation. I’m not sure it ever did, but especially now, my work as an actor does not define me. The nascent diminishment in my ability to download words and repeat them verbatim is just the latest ripple in the pond.

There are reasons for my lapses in memorisation – be they age, cognitive issues with the disease, distraction from the constant sensations of Parkinson’s, or lack of sensation because of the spine – but I read it as a simple message, an indicator.

There is a time for everything, and my time of putting in a 12-hour workday, and memorising seven pages of dialogue, is best behind me. At least for now.

In fairness to myself and to producers, directors, editors and poor, beleaguered script supervisors, not to mention actors who enjoy a little pace, I enter a second retirement. That could change, because everything changes. But if this is the end of my acting career, so be it.

This is an edited extract from No Time Like The Future: An Optimist Considers Mortality by Michael J. Fox (Hachette Australia, $32.99), out now.

MORE STELLAR