‘I believe that when she died, she set me free’: Tragedy that changed Leah Purcell’s life

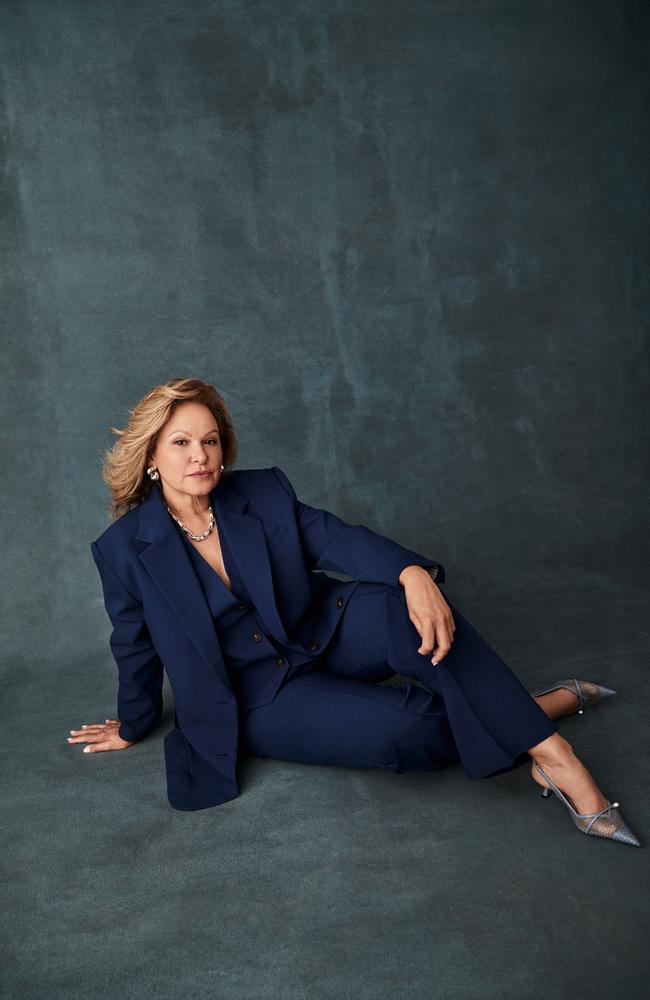

Leah Purcell opens up about her devastation over the Voice to Parliament result, the death of her mother – and the difficult but joyous childhood that shaped her, as he launches her new drama series.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For nearly 30 years, actor, director, producer and author Leah Purcell has thrown her heart and soul into every project she has worked on.

Along the way, she has sought to highlight the voices and stories of Indigenous Australians. As she prepares for the launch of her new series High Country, the 53-year-old joins Stellar’s podcast Something To Talk About to open up about her devastation over the Voice to Parliament result, the death of her mother – an event that, she says, “set me free” – and the difficult but joyous childhood that led her to where she is today.

On the importance of telling Indigenous stories:

“My Indigenous heritage comes from my mum’s side of the family. My dad, who’s white, didn’t have anything to do with my upbringing. I was brought up very Blak with culture and our community. My grandmother was part of the Stolen Generations. My mother was that generation; I call them ‘the lost’ because the assimilation policy from the government was forced upon them – culture was taken, language was taken, yet they were not accepted into white society. But they were supposed to conform to that.

So I call them the lost generation because they weren’t sure where they walked. They were women that definitely didn’t have a voice. I’m the youngest of seven, born in the ’70s, grew up through the ’80s, ’90s, and I’m at a time in life where I can have a voice. Through the arts, you can reach so many people and bring about understanding. I don’t like to call myself an educator because your opinions are yours, but if I can give an insight or an understanding to an Indigenous issue that often comes from the mouths of politicians, if I can bring that heartfelt and emotional connection because it’s my or my mother’s or my grandmother’s personal story, then no-one can deny me that story. Because to do that, then I don’t exist.”

Listen to the full interview with Leah Purcell on Stellar’s podcast, Something To Talk About:

On how she felt after the rejection of the Voice to Parliament in October last year: “Devastation. Heartbreaking. It actually made me reassess what I do in the industry. Does anyone care? I want to make a difference, so if I’m not making a difference in the arts with my voice and the stories, then why am I here? You know, maybe I should become a teacher and work with young people. I think it’s put us right back in some areas but then, in other areas, it puts an agenda for Treaty. But that’s a longer road … It was an opportunity for a voice and that voice was just to share as Blackfellas talking amongst Blackfellas that can bring it to our politicians, so they’re actually being instructed on what we, as a people, want. So it really floored me. I know [filmmaker] Rachel Perkins was behind the movement for that

Week of Silence [to grieve and reflect in response to the unsuccessful Indigenous Voice referendum]. I had functions that I had to attend and I said, ‘I can’t do this because I can’t pretend that it hasn’t affected me, and I can’t pretend that there aren’t people that are going to be in my audience that have voted no and are just getting on with life.’ It really struck a chord and it was really disappointing. I cried. I’m tearing up now. It was devastating.”

On how the death of her mother when she was 18 shaped who she is today:

“I fell pregnant when I was 17. I turned 18 in August. I had my daughter in September. My mum died in October. So it was ‘pull your socks up and survive’ because you’ve got your own daughter. And my mum always said, ‘Make sure you look after that little girl.’ She died of bowel cancer and she sort of stayed around for me to give birth and make sure we were all right. I believe that when she died, she set me free. I’m the youngest of seven, and if she was still alive, I’d be still in Murgon [a country town in Queensland] looking after her. She was a very talented woman. She lived with heartbreak; my father was never around. I saw her pain. Yes, she did drown it in a brown bottle of liquor. Then I’d see this other side of her where she was full of life and everyone looked up to her. My mother was doing reconciliation before the word became trendy. There would always be Blackfellas and white fellas in my kitchen in Perkins Street in Murgon. My mother was four foot nothing but could control a room against men that were giants. She’s my mother, my father, my hero. So for me to not do what I’m doing now would be an injustice to the pain that she suffered. And she set me free. She set me free.”

On being a mentor to people like Jessica Mauboy, who she directed in the 2016 series The Secret Daughter, and Rärriwuy Hick, who played her sister in the prison drama Wentworth in 2016:

“I love that they look up to me as a mentor. I wear that badge of honour proudly and I love giving back. That’s one of the joys of being a director, when you can manipulate, massage, mould, bring someone out and let their talent shine. It’s the biggest reward. When you see the people that you’ve mentored or nurtured – or even just sat down and had a cup of tea with and chewed the fat over the industry – and you see them take that on or a spark ignites in them, and then all of a sudden the little spark becomes a flame and they’re away. I can say that there are a couple of thousand young people I’ve nurtured and brought through and

that I am so proud of, other than my own two grandsons and my daughter.”

On saying no to projects she didn’t connect with when she was younger:

“Cheeky I was! My first film was [2001’s] Lantana. I was very spoilt to be working with some elite people. Not that we were snooty at the project, but we were very spoilt to be working with great actors, great directors, great writers. I said no to a few, not that there was anything wrong with them, but at that time I wasn’t interested in the story. There was one, I read the first five pages and couldn’t connect. I knew the editor and I rung her and she said, ‘Yeah, no, we got rid of those first five.’ And I went, ‘Ah, bummer.’ What I learnt from that is reach out, ask questions, see who else is involved and what they think of the project. So whether I said yes or no, I learnt from that experience.”

On playing a detective in the new series High Country and why people love watching crime dramas:

“I think it’s the mystery. As a viewer at home, if you’ve got a good crime story and there’s intrigue and there’s edgy drama and there’s the thrill aspect, you’re always wanting to try to be one step ahead of the story or you’re trying to work it out. It makes for great family debate if you’re all watching it. I think that’s a big thing, where people can sit down and chew the fat over ‘What do you think?’ and ‘What’s this?’ and ‘Where’s this turning?’ And then you can surprise your audience with, ‘Oh my gosh, I never saw that coming.’ With my experience now of working on those TV shows in that genre, I can sort of predict the ending in some. Every now and then I try to go, ‘No, I don’t want to actually debate it. I just want to let it unfold and get caught up.’ But you do feel pretty smug when you can work it out.”

On being a cultural advisor on High Country [Purcell is also executive producer]:

“I’ve done a few cultural advising on shows where they’ll get me to come in and do the Indigenous role and then I’ll go, ‘Yeah, but there’s more than just casting an Indigenous person in the Blak role.’ There are protocols that need to be undertaken with what that storyline might be. So with High Country, because we were having the story of the Taungurung people … it’s a general Dreaming story so it’s nothing sacred and I made sure that we were sort of one step removed from it so that we could just tell the story – but it’s about seeking permissions from the elders, collaborating with them so that they are across what we’re going to do with the story, how much content will be in the film. So it’s another hat that I got to wear and, you know, if I thought my shoulders were wide before with being a mentor, it’s even wider with cultural consulting, because that’s what I tell people – I said, ‘If anything goes wrong, it’s not you that will get in trouble. It’s me, because I’ve put myself out there.’ And there’s always someone out there sort of second-guessing, ‘Where did you get that story from?’ And I go, ‘Look, I cross my Ts and I dot my Is, and I got all the elders’ and I always name them off. And it makes the community feel heard, you know, that they do have a voice in their stories getting out there.”

On the loyalty of Wentworth fans [the series began in 2013 and ended in 2021]:

“Wentworth fans are the best. They’re outrageous. One of the fans bought me a star and had my name attached somewhere out there in the universe. A friend found the coordinates and took a photo of it and said, ‘Here’s your star.’ So that was just next level. I’ve had a few, what’s the dolls with the wobbly heads called? Bobble dolls. There’s a Rita Connors [her character]. And there’s even a Drover’s Wife one, a Molly Johnson [from the award-winning 2021 film The Drover’s Wife: The Legend Of Molly Johnson, written and directed by and starring Purcell]. The fans are loyal and they’re really cool, and they’re very protective, as well.”

On finding the motivation to give anything a go – including being a support act for singer Shania Twain:

“I think it just goes back to my nan and my mum not having a voice. So whether I was going to be a director, a writer, an actor, a mother, a garbage collector, work in a cafe shop –

I think I was always going to be the best at whatever I chose to do, for them. That was my motivation and determination and then, look, whether it’s because I’m a Leo, I had the guts to go, ‘I’ll give it a crack’. I got through high school as a C-average student. If I acted in anything, I got an A. I was very fortunate that the high school I went to had a three-month high school musical that we worked on. I can’t read music, but I sing – I had a band. My big claim to fame in the late ’90s or early 2000s was that I supported Shania Twain when she was the biggest singer in the country. I was her support act here, we [toured along] the east coast. I just had my little band, I did pub gigs in Sydney at Strawberry Hills Hotel, round midnight up [Kings] Cross every Wednesday night. So I could sing a song, but every time I’d go in [to audition for professional stage musicals], I don’t know whether it was nerves or something … I just said it obviously wasn’t meant to be the path that I went down, you know? But I love a good musical. I’m always a guest at them. I’m sitting there and my toes are tapping and I’m singing along.”

High Country premieres on March 19 on Binge and Foxtel. Listen to the full interview with Leah Purcell on Stellar’s podcast, Something To Talk About: