Exclusive: Inside the dying days of Silverchair, drummer Ben Gillies and bassist Chris Joannou speak

In an explosive extract from their new memoir, drummer Ben Gillies and bassist Chris Joannou address how heavy drinking and increasing tensions with Daniel Johns signalled the beginning of the band’s end.

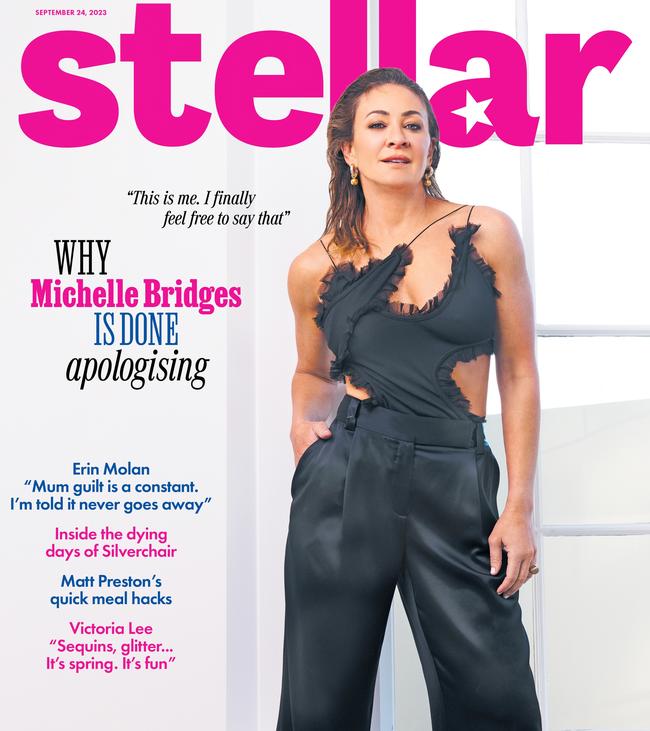

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Garage bands dream of hitting the big time, all the time. But in 1994, three 15-year-old boys from Newcastle – recording as Silverchair – did just that when their grunge anthem ‘Tomorrow’ propelled them into Australian rock history and a career that would garner them 21 ARIA awards. But with that sudden fame would come addiction, illness and discord.

In this exclusive extract from their new memoir Love & Pain, drummer Ben Gillies and bass player Chris Joannou address the painful events of 2007, when heavy drinking and increasing tensions with lead singer Daniel Johns signalled the beginning of the end for the band

Chris Joannou

New York, United States, 2007

The crowd surged forward with force. They’d been waiting more than three years for this: our first international show since the Across The Night tour in 2003. We made our global comeback at The Bowery Ballroom in New York.

Our show was sold out and standing room only. We opened with the tried-and-tested ‘Without You’ from Diorama and the crowd sang along with Dan, word for word. “I’m not nervous anymore,” Dan declared, as we launched into the new ‘Young Modern Station’. When we got to our first single from the new album, ‘Straight Lines’, it became an all-out singalong. It was a good sign.

After the audience demanded an encore, we returned to the stage to rip out ‘If You Keep Losing Sleep’. We ended things in a blaze of drumming glory from Ben with ‘The Lever’.

We’d put so much effort into the record [2007’s Young Modern], and with the same intensity, we threw ourselves into pre-promotion and tour planning. I swear I could feel the groundswell. We knew whatever we were doing was working. When ‘Straight Lines’ dropped in Australia, it spent six weeks at the number-one spot.

After teaser shows in Toronto and Los Angeles, we headed back to Australia to rehearse for the Young Modern tour. We played shows at The Metro in Melbourne, Thebarton Theatre in Adelaide, the Metropolis in Perth, the Enmore Theatre in Sydney and [music festival] Groovin the Moo in Maitland. While we were preparing to take the tour overseas, we announced an Australian tour with Powderfinger called Across The Great Divide. Tickets went on sale for one tour when we landed in LA to start the other. It was all happening…

We headed to the UK, then on to [mainland] Europe. It was in Paris where things fell off the rails. We were talking to our lighting guy when Dan got a phone call. This was an hour before we were due onstage. It was obvious he was dealing with a serious personal issue. I’ll never forget the look on his face. Ben went to see if he was OK. He wasn’t.

Dan had to leave right away and go back to London. “Go, go,” we said. “Do what you have to do.”

There was never any question that Dan needed to go. We never would have asked him to stay to see out the gig. Dan was on a train to London before the promoter even got to the venue. We gave the excuse that Dan was sick and the show was scrapped. We didn’t ever like cancelling shows, but some things are more important. We supported Dan’s choice to leave, and had his back with the fallout from the show being cancelled.

We didn’t – or couldn’t – see it at the time, but things were falling apart. By the end of the Young Modern tour, our no‑drinking phase was well and truly over. We were taking bottles of vodka onstage with us. For a band who never used to drink before or during shows, we were on a slippery slope. While we were playing, we were sure that the swigs of vodka weren’t affecting our performances, but of course they were.

The cycle had begun. The wick was lit, and the candle was burning dangerously close to the curtains.

Ben Gillies

Newcastle, Australia, 2007

The drinking culture that had started on the Young Modern tour didn’t just carry through to Across The Great Divide – it escalated. I escalated. I pushed things too far and I couldn’t pull back. At first, drinking was fun. Post-show, it was a release, a party-starter, an un-inhibitor (not that I needed the last one). Drinking was casual, until it wasn’t. In my late 20s, something clicked inside me. I couldn’t have a glass of something and stop there. I had to wipe myself out. Drinking stopped being fun and started becoming a problem. The dark side of drinking eclipsed the momentary high.

Before the darkness, there was always the twilight. It was the sweet spot. For me, I hit that spot after approximately 2.5 drinks. That was where the magic happened; things looked brighter, felt better and sounded sharper. Any less and I was too straight. Any more, and I was too wobbly. The thing with twilight was that it sat on the edge of a cliff.

I dropped off that cliff a few times.

For a long time, my drinking didn’t affect my work. Like I’ve said, in the beginning I didn’t drink before shows, and even later on I’d never drink more than a single beer before a show. Drumming required me to keep sharp. And I tried to keep things on the rails the rest of the time. Emphasis on the word “tried”. I wasn’t always successful in my attempts.

The Young Modern tour was when things really started to get out of hand. We were drinking all the time. There were a few moments when I took it too far.

At the peak of my struggle, I called our manager, John Watson. “I think I have a bit of an issue,” I admitted to him. “I’m just on the tail end of a bender, I’ve gone way too hard.”

“I get it,” he told me. “This is what I think: you guys have never lived a normal life. From the start of high school, you lived an extraordinary life with the highest of highs. It was like you were riding on the tip of a 20-foot wave, and then the wave would crash, and you’d just be back at home like nothing ever happened. Because you’ve always lived riding these highs, you’re going to chase them wherever you can find them.”

It made sense. I was chasing the rush of my youth. But I couldn’t catch it. And so, I drank. I drank to chase the rush, and I drank to drown my sorrows when it slipped between my fingers. I drank, and I drank. I drank enough for a few lifetimes.

This is an edited extract from Love & Pain (Hachette Australia, $44.99) by Ben Gillies and Chris Joannou, out on Wednesday.