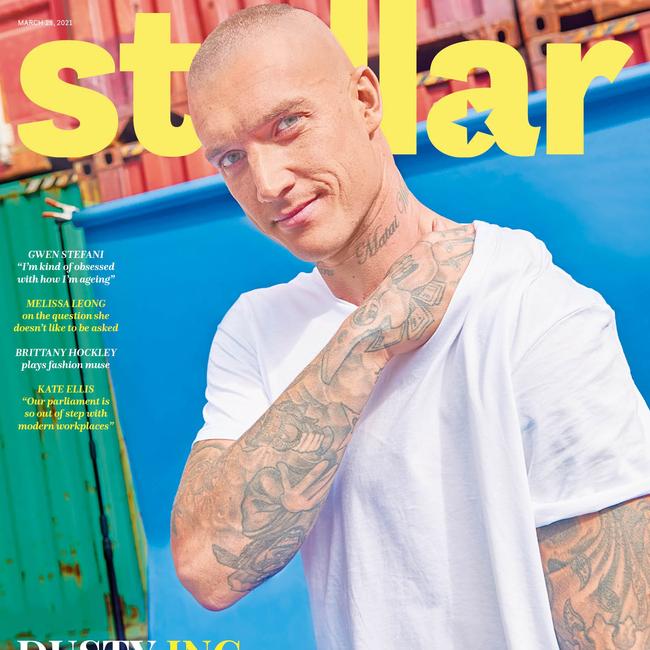

AFL’s Dustin ‘Dusty’ Martin on mental health and his bad-boy image

In a very rare interview, AFL star Dustin Martin tackles questions about his upbringing, his mental-health struggles, and what he really thinks of his bad-boy image.

Stellar

Don't miss out on the headlines from Stellar. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Talking with Dustin Martin is more about what he will not say than what he will.

He’s the biggest phenomenon in Australian sport, the first AFL player to win three best-on-ground medals in the grand final. Every footy fan – and plenty who never watch – knows him by his first name.

“Dusty” is AFL’s most marketable sporting commodity. Yet almost no-one really knows who he is – and that’s how he likes it. Martin says he doesn’t care what people think of him, because the only opinion that matters is his own.

As such, he tells Stellar, “I don’t know if I’m misunderstood or not. I just keep trying to be the best person I can. People are quick to pass judgement on one another, but you never really know what people are going through or have been through. We are all imperfect, we are all living and learning, and I just try to do my best every day.”

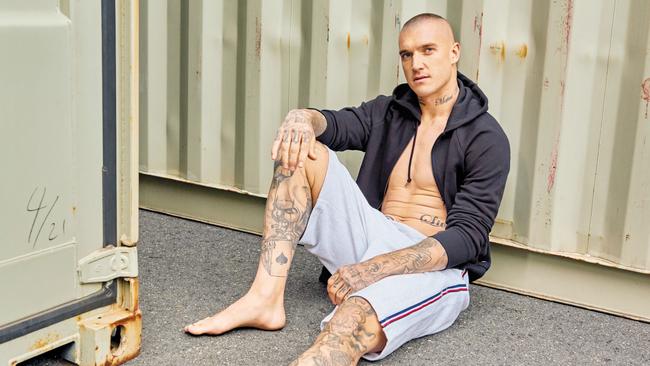

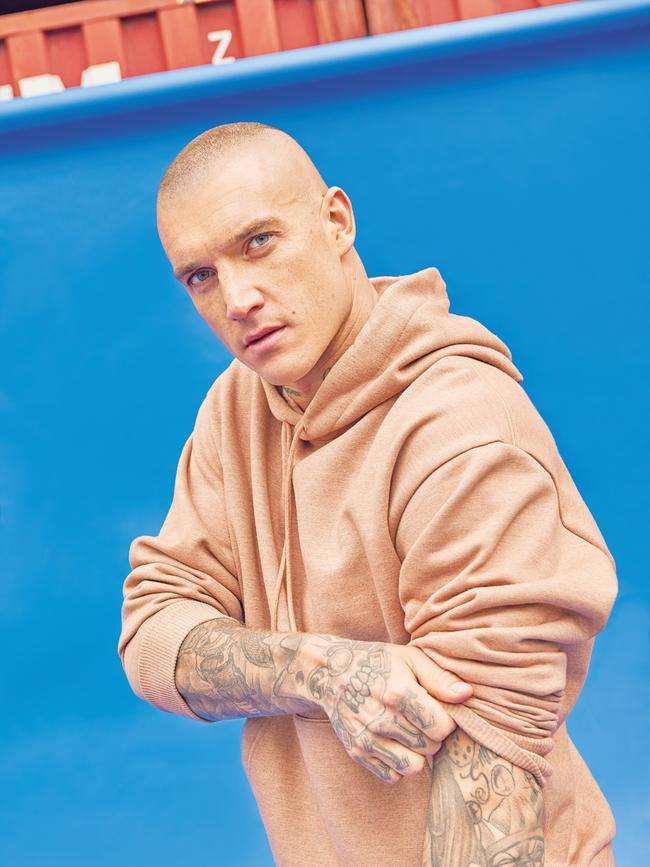

At his Stellar photo shoot on the docks of Port Melbourne, Martin is a cooperative and friendly presence. He will talk about his sponsors, the beginnings of “Dusty Inc.” and how he hopes to feature in the fashion industry after his sporting career ends.

He will expand on his love of kids, his troubles with phones (he hates phone covers and refuses to use them), and his fondness for sports documentaries, which teach him new things about elite performance.

He will show off his new tattoos, which include three premiership tatts – for 2017, 2019 and 2020 – that were inked on his thigh at about 6am the morning after last year’s grand final.

But he won’t talk about relationships.

Or the marriage breakdown of his coach, Damien Hardwick, except to say it will have “no impact” on Richmond’s plans to extend its grand-final dynasty.

He declines to discuss his father, Shane, whom he regularly visits in New Zealand after Shane was deported in 2016 for associating with criminal enterprise. And he doesn’t touch upon the intense scrutiny that trails the best performers in every sport, except to say that Sydney is “refreshing” because it is “different” to Melbourne.

Martin doesn’t give many media interviews. He doesn’t say much at all in public beyond the post-game clichés about the boys digging in and taking it one week at a time. As a journalist once said, Martin is a puzzle to be solved. He is hidden in plain sight, and has been since his AFL career began with 18 touches in a 2010 game.

Richmond chief executive Brendon Gale tries to explain the cult of Dusty, telling Stellar, “The public don’t know him. He’s hard to know. He’s a very soulful, passive sort of guy. [It is] a complete juxtaposition to the way he plays, which is ballistic and bombastic.”

Outside of Melbourne, Martin is a bad boy who dipped into sleeping pills one night and who was once accused of the boozy menacing of a woman at a restaurant after she asked him to quieten down. On the field, he rises to those moments that matter most. His “Don’t Argue” signature push off is much imitated by other players, mostly poorly.

Perhaps the most influential player of a generation, Martin’s mohawk styling denotes his warrior bearing, as though he has been lifted from a long-ago war and asked to put down his tomahawk. He harks back to footballing greats such as Wayne Carey, or Gary Ablett Sr, when the match result rests on his exploits and the other 35 players on the field double as observers.

At 29, Martin is growing up. If he’s “grateful” for the million-dollar contracts, he’s come to appreciate that the pursuit of happiness isn’t driven by material gains. He speaks of mindfulness to combat the empty feeling after he won his first flag in 2017. He reads, has kept a daily journal and taken cooking classes – all choices that don’t easily sit with his public reputation for toughness.

“I think most people at some stage in their lives go through a similar thing,” he says of his post-2017 blues. “I just think it’s important to be open and honest, and talk about your feelings with someone.”

Martin grew up in Castlemaine, north of Melbourne, one of three brothers; his parents separated when he was a child. These were formative years. The brothers played football in a paddock where they erected goalposts, as well as in the home hallway. Martin always had a football in his hands.

“I was out in the paddock snapping goals from the boundary and pretending I was on the MCG,” he says. “People often ask me how I do certain things and the reality is that I’ve been practising since I was five or six.”

He credits hardships for teaching him appreciation. Asked about his parents, he recalls, “They let us live and learn, but were always there to put us back in line and teach us discipline and important life lessons.” He left school in Year 9, a regret, and moved to Sydney to be with his father. He hated the succession of menial jobs that followed, but learnt from them.

When he was 16, Martin dedicated his future to giving himself the best chance of playing elite footy. A self-motivator, he has always projected a strong sense of himself. “He didn’t come from easy street,” Gale tells Stellar.

“The challenges and insecurities and doubts from adolescence into adulthood… we all battle those. For a guy to prevail in the most public of ways – we like that, don’t we?”

After the 2019 grand final, Martin collected his car from the MCG carpark – 65 days after the game. In that time, he had been spotted in Las Vegas and the Maldives, where he hung out with new friends like Serena Williams and her husband.

After last year’s grand final, he stayed on the Gold Coast for a month or so with some close mates, and absorbed the laidback lifestyle of Queensland. “We partied pretty hard and had a lot of fun,” he says. “But we also got some good training and relaxing in.”

He claims he is more motivated than ever, and nods to suggestions he could go on and on, much like American footballer Tom Brady, who recently clinched his seventh Super Bowl win, aged 43. “I’m obsessed with the process of becoming the best I can as a person and an athlete,” he says.

“It’s amazing what Tom Brady has been able to achieve. It’s amazing what you can do when you believe in yourself. My preparation hasn’t changed that much over the years; I’ve just refined it. I am always researching things that can better my performance.”

He says he endorses only products that match his values – authenticity, loyalty, compassion, empathy, positivity and honesty – and his alignments range from Bonds to brands such as Jeep, Nike, Kennedy, Voost and Archies. His bent for fashion is about expressing himself, he says.

It’s a side rarely glimpsed, along with a playfulness that’s defied the scrutiny. “He cares about things,” Gale says. “He is always evolving, learning and growing. That’s a side the public don’t see.”

After last year’s grand final, Martin sent Richmond club president Peggy O’Neal a text message: “We won, we won, we won.” His boyish exuberance extends to kids. Martin can often be spotted, on the floor, playing with the children of his teammates.

“I just remember as a kid I had a lot of great people I looked up to – my mum, dad, aunties and uncles – and they were always fun to be around and looked after me,” Martin says. “So I guess I try and be that kind of ‘fun uncle’ for the kids – and be there for them.”