Hidden horrors of forced marriages laid bare as victims details nightmare experience

Raped, beaten, kept as a domestic slave – these are the hidden horrors of forced marriages happening in Australia and the nightmare Sabrina fought so desperately to avoid.

Marriage

Don't miss out on the headlines from Marriage. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Sabrina cannot recall the number of strangers willing to marry her, but it’s safe to say there were more than 50.

As the eldest child of immigrants, who moved to Australia when she was one, her family was keen for her to marry someone from their ethnic community.

As is custom, senior community members were involved in the matchmaking process, and potential suitors would come through a WhatsApp group.

“It’s almost like headhunting,” the now 26 year old from Sydney whose name has been changed, said. “Like when recruiters do it for a job, except community members will do it for couples.”

The first proposal came though when she was just 17.

By the age of 21, despite being open to an arranged marriage, she had not found love and was told by her parents to meet a man overseas who they wanted her to marry.

“I would say I have a pretty strong voice, but in that situation I just froze,” Sabrina said.

She knew others in her community who had been pushed into a forced marriage – when at least one party doesn’t consent – and she didn’t want that. She reached out to My Blue Sky, which supports people like her and other forms of modern slavery, who said they could help her put a ban on her passport, but she feared her parents would get into trouble.

Instead she bought a burner phone, SIM card, got some local currency, which she hid in a sanitary pad wrapper, in case she needed to escape.

In desperation, she even tried to put on weight and packed high heels, to try and put off her suitor, who was a shorter man.

It didn’t, with the man saying he was happy to go ahead. She said no.

“I got taken out of the cafe in front of everyone, got yelled at, called all sorts of names and things by my parents because they were very, very upset, and embarrassed in front of everyone,” Sabrina said. I remember my mum saying, ‘Think about your dad’s honour’. And I said, ‘What about me? What about my honour?’”.

Sabrina feels if she had been younger she may have succumbed to the pressure, like Ruqia Haidari, who was from the Hazara community in Shepparton, Victoria, and forced to marry her first husband in a religious ceremony at 15, divorcing him when she was 20. Her mum then arranged for her to marry a second man. Six weeks later he killed her.

In May, Ruqia’s mum, Sakina Muhammad Jan, became the first person in Australia to be found guilty of arranging a forced marriage.

In another case two Saudi sisters sought sanctuary in Australia over claims at least one was being pushed into a forced marriage. Tragically they died in what police believe was a suicide pact.

Melbourne lawyer Ajsela Siskovic works at InTouch, a family violence practice for migrant and refugee women and sees up to two cases of forced marriage a week. She said victims come from every country and culture, although she tends to see higher numbers from Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan and India.

“A lot of our clients are forced to be married overseas, and then brought to Australia,” Ms Siskovic said. “So they are often young. Dowries are paid. They bribe the family, essentially and then these girls have very no choice. These are some of the most isolated and abused people in Australia, often living in domestic servitude.”

One woman living in South Australia was raped, beaten and kept as a domestic slave.

“If you read her statement, you would be horrified, like, ‘Is this really happening in modern day Australia?’,” Ms Siskovic said.

But forced marriage also happens to men. Bijan Kardouni, a gay man who left Iran for fear of the death penalty, helps migrants arriving in Australia, among them victims of forced marriage.

He said currently the mother of a gay man, a Kenyan from a strict Christian background, is putting him under enormous pressure to marry a woman. “Some think forcing their child to marry will cure them, that it will make them straight,” Mr Kardouni said.

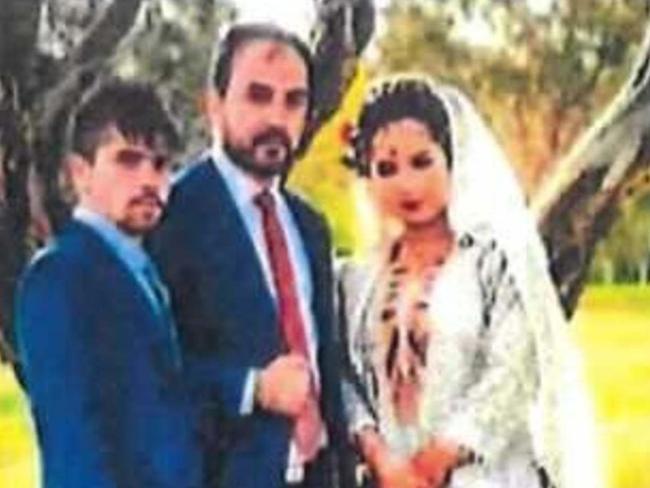

Roia Atmar was 14 and an Afghan refugee living in Pakistan in the 1990s, when her family arranged for her to marry an Afghan man already living in Australia.

While she never protested about the arrangement, she never had a say about who she was marrying. Today under Australian law it would be considered a forced marriage, as she was under 16 and too young to consent.

Worse for her, the man chosen was much older, in his 30s, and a vicious, controlling bully, who set her alight causing 35 per cent burns to her body.

She is keen to let abused women know – especially those who have just arrived from overseas – there is help available.

“The system saved me,” Ms Atmar, a mother-of-four, said. “When I needed help the system worked, it protected me and my children.”

Sabrina, now 26, said it took a long time to repair the relationship with her parents, but she found someone herself from the community who she fell in love with and married at 24, with her parent’s blessing.

“My parents only wanted the best for me,” Sabrina said “My way took a little longer, but it worked out in the end.”