‘Why do Indigenous people have a shorter life expectancy?’

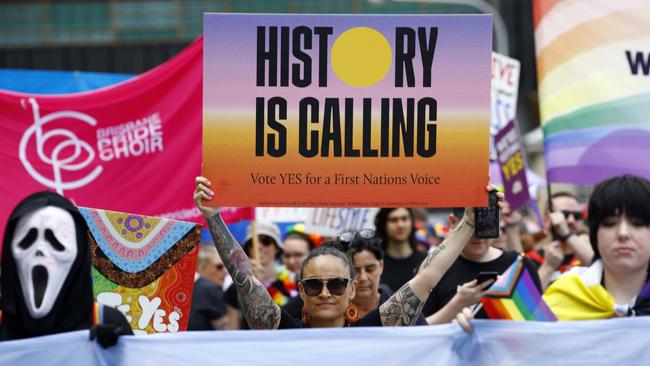

It’s an alarming claim made in an advert by the Yes campaign but can it really be true in Australia today?

Illness

Don't miss out on the headlines from Illness. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Welcome to Ask Doctor Zac, a weekly column from news.com.au. This week, Dr Zac Turner explains what health issues Indigenous people face.

Question: Hi Dr Zac, I’ve been following the Voice to Parliament referendum closely and I noticed an alarming advertisement from the Yes campaign that talked about Indigenous people having a significantly lower life expectancy than non-Indigenous Australians.

Why is this so? This is shocking if it’s true. – Dave, WA

Answer: Yes it is true. Yes it is shocking. The gap in life expectancy to the Australia average is 7.8 years for females and 8.6 years for males, though it wasn’t so long ago that it was 20+ years.

‘Why’ is a big question.

The answer to this question lies within conversations about health, science, economics and government. Many of these conversations are happening right now loudly across our nation.

‘What can be done’ is the follow up question, which led me to studying medicine in the first place. I believe there are some answers, however, we must be asking the right questions.

Having grown up in literally out ‘the Back-o-Bourke’ and several other small rural towns, it was shocking to me that my Indigenous Australian friends would live on average 20 years less at that time.

To put it in perspective, how old are your parents? How old are you? What is your 20-year plan? Before 2000, when non-Indigenous life span was around 70 years, that meant my friends would potentially die of treatable issues by their early 50s.

The life expectancy gap is a staggeringly high disparity between populations in one country, especially a developed and prosperous nation where equitable access to health care is available to all.

Some may argue the gap between life expectancy has tightened in the past ten years because more Australians now identify as Aboriginal, but ask any epidemiologist who identifies patterns and trends across populations, simply increasing the sample size of ‘healthy’ individuals does not erase a concerning pattern of health or disease.

I believe all Australians would agree: A gap in life expectancy exists and this is not OK.

I encourage readers to really think about this. Aboriginal people have thrived for over 60,000 years, and only since colonialism have they been coming up short in health outcomes. Yet we are eager to instinctively lay blame at their feet.

Yes, many people argue that resources have been given to Indigenous Australians, but non-Indigenous understanding of what needs to happen to create change has been left without proper consultation. Furthermore, many of the funding routes and opportunities that have been allocated by one government have then been swiftly changed by the next.

Could you even imagine whole hospitals or health departments being started at the beginning of an election term and then taken away after four years? What would you do?

Bush medicine has supported the health of Indigenous Australians for an impressively long time. Kakadu plum, snake vine, witchetty grubs are just some of the multitude of medicines, illness preventions and health promoting interventions used by Indigenous Australians for 60,000 years. We could benefit a lot by learning from their approach to health.

Many of our greatest discoveries in medicine from analgesia, blood thinners and antibiotics all have origins in nature. The health benefits of many traditional Indigenous bush medicines are only now showing us great opportunities to better every Australian’s health.

Life expectancy is measured by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), and covers not only health, but also social factors such as education, employment, housing and income. These social factors (the social determinants of health) are responsible for at least a third of the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

From the outset, Indigenous Australians have higher rates of chronic health conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory illnesses. Indigenous Australians also often experience socio-economic disadvantage, which is closely linked to health outcomes as it limits access to healthcare, nutritious food, and safe housing.

In light of all of the above it is heartbreaking, when you consider an Aboriginal person born today will already be more likely to die sooner than a non-Indigenous child. This isn’t an easy fix. We need better guidance to support the development of better health approaches.

The continuous feedback from a body such as the Voice may just be the assistance we need in closing this gap. It could deliver life expectancy equitable to that of the entire nation, not just in statistics and numbers but in real-life health improvements.

Indigenous communities, particularly those in remote and rural areas, may have limited access to healthcare facilities and services. Indigenous people often see the hospital as a place for dying, and can prolong or avoid visiting wherever possible, until it’s too late.

Indigenous Australians have reported feeling reluctant to seek healthcare due to past traumatic experiences of cultural insensitivity, lack of culturally appropriate healthcare services, or language barriers. It makes sense, therefore, to include Indigenous people as part of the solutions in overcoming these barriers in policy and promotion.

Health care providers cannot change and modify their approaches without the knowledge and understanding of culturally appropriate care. There is a disappointing level of training available for health care students across medical, nursing and allied health to better understand how to treat and care for Aboriginal patients. If we aren’t training our future health professionals how to provide culturally appropriate care to Aboriginal patients, we may never close the life expectancy gap.

The opportunity to close the gap is upon us. It’s not a research project which outlines outcomes and targets to the government which, are debated for years resulting in very little changes. It’s not the adoption of restrictive and oppressive policy that fails to recognise or understand cultural differences. And it’s not a tax whereby we throw money at a problem and hope it gets solved.

It is an opportunity to establish a framework for an ongoing conversation. A conversation where we can learn more, understand more and in turn, do better and make the difference we all want to see happen. We can close the gap. Nothing is impossible. We can achieve this with the help of the Voice. The conversation, so desperately needed to genuinely close this gap, starts with the help of the Voice.

Whatever we have been trying thus far hasn’t been working in a way that can’t be improved. By allocating a place in our constitution for consultation that can’t be changed between elections will allow Indigenous people to finally have a Voice in their health.

Got a question: askdrzac@conciergedoctors.com.au or follow Dr Zac on Instagram

Dr Zac Turner is a medical practitioner specialising in preventive health and wellness. He has four health/medical degrees – Bachelor of Medicine/Bachelor of Surgery at the University of Sydney, Bachelor of Nursing at Central Queensland University, and Bachelor of Biomedical Science at the University of the Sunshine Coast. He is a registrar for the Australian College of Rural and Remote Medicine, and is completing a PhD in Biomedical Engineering (UNSW). Dr Zac is the medical director for his own holistic wellness medical clinics throughout Australia, Concierge Doctors.

Originally published as ‘Why do Indigenous people have a shorter life expectancy?’