Inside the Mexican clinic defying Aussie doctors and saving our kids

THESE Australian parents were told their kids had little hope as they battled brain cancer. Now a controversial Mexican cancer clinic is helping their tumours shrink or even disappear.

Illness

Don't miss out on the headlines from Illness. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WORLD EXCLUSIVE

HANDED a death sentence and told to “go home and make memories”, 70 families from across the globe have put their faith and lifesavings into a controversial Mexican cancer clinic.

Now for the first time, News Corp Australia goes inside the doors of Monterrey’s Clinica 0-19, where some children with brain cancer are finding new hope as their tumours shrink and, in several cases, disappear.

Neither the clinic nor families of children with Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG) say they are cured, just that their symptoms have improved.

But this is more than the grateful families — including three from Australia — were told to expect when their children were diagnosed with one of the most deadly forms of brain cancer.

“If we had not gone to Monterrey and started the treatment last year, then I would not have my daughter today,” says Melbourne father Vivek Kulkarni. His seven-year-old daughter Riaa’s tumour reduced by 40 per cent after one treatment.

MORE: Fundraising for Riaa Kulkarni

MORE: The woman tirelessly raising money for brain cancer research after her son’s death

“In August I went to my (Australian oncology) team and they said she only had weeks to live, because she wasn’t walking and she was going downhill rapidly.

“Now I still have her, and she is going to school.”

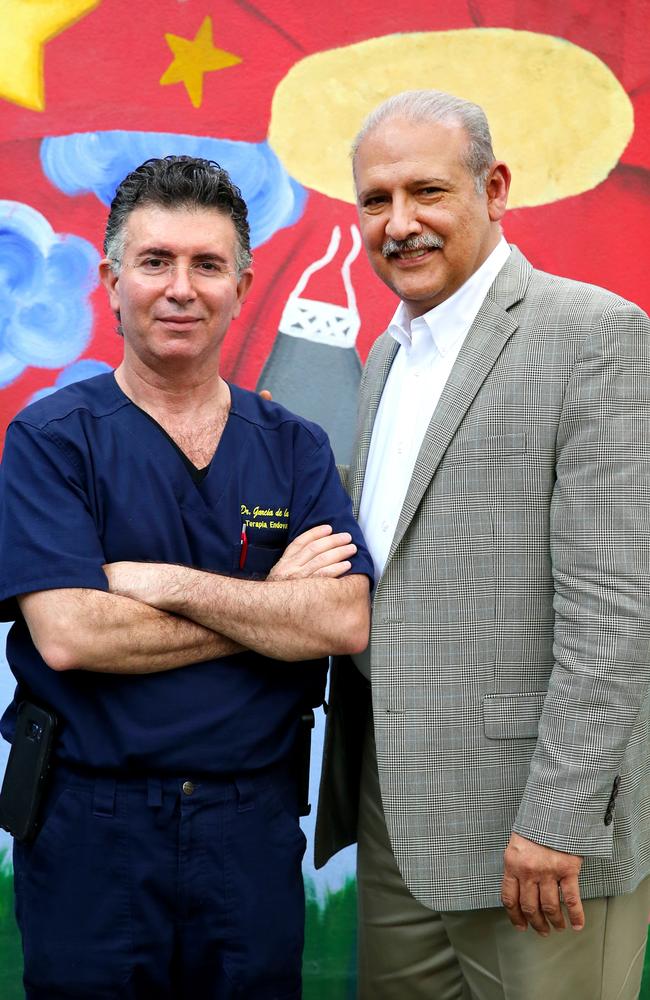

Paediatric oncologist Dr Alberto Siller and interventional neuroradiologist Dr Alberto Garcia say they don’t advertise their treatment but have been overwhelmed with desperate families from Australia to Europe, America and Asia since they regularly began offering it in January last year.

The pair is scorned by the international medical community, some of whom label them as cowboys preying on vulnerable parents of dying children. They question their science, the drugs they use and the scans with which they judge tumour size.

MORE: $100m research plan to double brain cancer survival

“I told an Italian doctor, she was very critical of our work: ‘If you have something to give to your patient better than what we are using, feel free. We don’t need to see your patient, your patient belongs to your country and to you’,” Dr Siller said.

“We are not saying to anybody that we are going to cure (the cancer). We are not saying that we are the final solution. All we are doing is our regular job with the best we can do, and the results are talking for us.

“We don’t want to get into trouble with these good doctors in Australia or any other places.”

Leading Australian paediatric oncologist, Professor David Ziegler, has been highly critical of the doctors over the fact they have never released their research and findings to be peer reviewed.

“I have not seen any results that show this treatment is effective,” said Prof Ziegler,

Paediatric Oncologist at the Kids Cancer Centre, Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick.

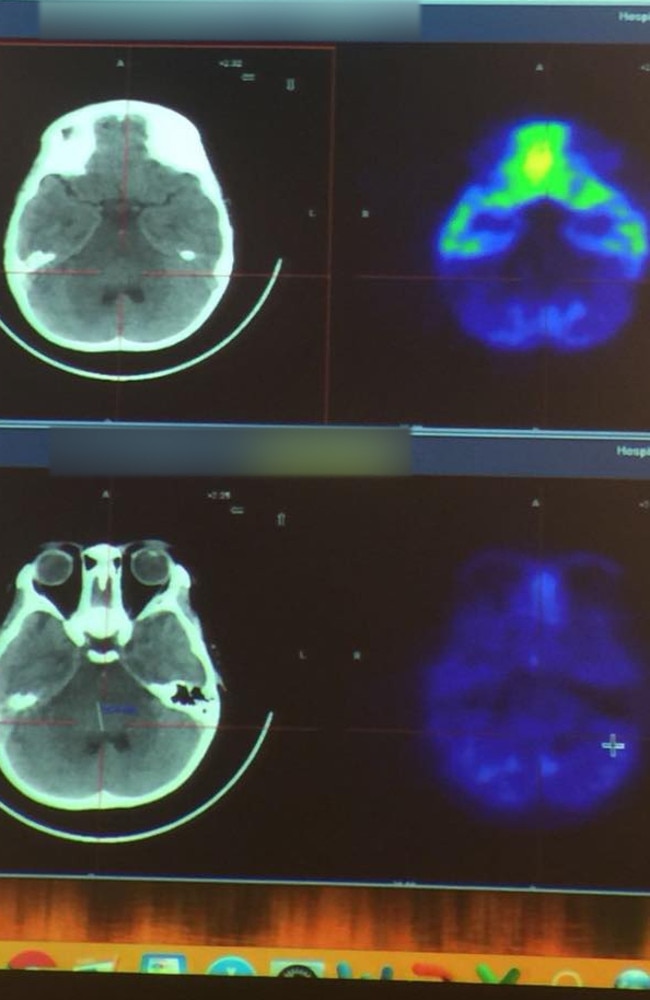

“On occasion the team in Mexico has released limited scans which do not accurately depict the tumour and are not able to be used to tell if the treatment is doing anything at all.

“If they have found an effective treatment for DIPG as they claim, then they have a moral obligation to publish their results to benefit children around the world who are dying of this disease.”

“Unfortunately when parents are desperate to save their children, there are people who are willing to take advantage of them, knowing that they will spare no expense if they think it may help their child.”

Dr Siller and his colleague Dr Garcia use a customised mix of chemotherapy drugs to directly target the brain stem tumours, as opposed to regular chemotherapy, which attacks the whole body.

MORE: Johnny Ruffo says he would have died in his sleep without emergency brain surgery

The treatments cost about $30,000 each and while their program varies for each patient, the usual regimen is one every three weeks.

If the treatment is effective — meaning a combination of MRI and PET-CT scans show a reduction in tumour size — they spread them out to several months apart.

They say they have four patients showing “no evidence of disease (NED)”, including someone they treated several years ago.

The clinic said it was trying to put us in touch with this patient, who they said is still alive and lives overseas, but this had not happened before we went to press.

MORE: Fundraising for Annabelle Potts

MORE: Fundraising for Annabelle Nguyen

Australian preschoolers Annabelle Potts, four, and Annabelle Nguyen, five, have this month been told they are showing no sign of their tumours.

Annabelle Nguyen was diagnosed in 2015, has been living in Mexico with her parents since May and was this month declared NED after her ninth treatment.

“The doctors have always been very clear with us. They have never promised us any cure, but they said at least we can try to maybe prolong her life,” her mum Sandy Nguyen said last week.

“We knew that from the very beginning. But there is always (the possibility of) a miracle, right, and any day is a miracle for us. We never expected NED.”

Her parents know Annabelle still has a huge fight ahead of her and last week was suffering from swelling in her brain that impacted her movement and made her very sleepy.

Sandy and her husband Henry Nguyen, have spent $300,000 on her treatment so far, money which they raised from selling their Perth home and borrowing from Henry’s parents.

They don’t consider it a high price to pay for the ten treatments they have received over the past nine months. Included in that cost are their living expenses in Mexico as well as scans and time in hospital.

“Just to have had this time is priceless for us,” Mrs Nguyen said.

Dr Siller said the clinic wasn’t making much profit from the DIPG treatment, which has rapidly grown to make up the bulk of their business over the past 15 months.

“We are not wealthy men,” he said.

They now employ ten physicians and a clinic co-ordinator who is fielding up to five requests a week from families. The clinic is where the doctors consult with the patients, who are treated in different local private hospitals with whom they have worked out a package deal to bring costs down.

“With the treatment, 75 probably almost 80 per cent, of our costs are devoted to the buying of medicines,” Dr Siller said.

“The rest is salaries of everyone including us.”

The doctors said they don’t advertise their work and that most of their patients find out about them on the internet.

“We are so busy doing different things, that it’s basically families’ work,” Dr Siller said of how their patients made their way to northern Mexico.

“Once they find they have the diagnosis, they look on the internet for information about what the disease is about, and also about treatment. For that reason, they finally get a special blog that DIPG parents have, and that’s why they find about us.”

The practice is in a modest concrete building next to a construction site on a hill in a middle class neighbourhood housing dozens of private hospitals and clinics.

Mexico’s ninth largest city, Monterrey has in recent years transformed from the capital of a region blighted by violent drug crime into an aggressively modern and industrialised centre. Just 230km from the US border, it is also highly “Americanised” and draws thousands of medical tourists each year.

The doctors denied claims they were being secretive with their research and results, saying were simply “overrun with demand” and in a “race” to save their patients, for whom they were working 18 hour days.

“We are starting to do some basic numbers,” Dr Siller said.

“Our thoughts are to start publishing the results in the next coming months.”

They also said all their drugs were approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, but that their effectiveness was helped by the fact they were using new combinations they were adapting as they treated each patient.

“We know the risk, so we don’t take extra risks. All of the drugs are FDA-approved,” Dr Siller said.

“What has taken us so many years is to figure out sequences of drugs and combinations of drugs. That’s a main problem that other parts have in the world.”

AUSSIE DOCTORS WARN ABOUT MEXICAN CANCER CLINIC

AUSTRALIAN doctors are not alone in criticising Mexican doctors Alberto Siller and Alberto Garcia’s cancer treatment.

Physicians from around the world have warned they are taking unnecessary risks, using unproven science and drug combinations, and perhaps worst of all, taking financial advantage of parents who would do anything to save their children.

They accuse Clinica 0-19 of refusing to share its research, using unauthorised drugs and backing up their findings with unscientific scans.

While Dr Siller admitted last week they are to an extent making things up as they go along, he said this was driving their success.

He said the main problem with established medical protocol was that “you cannot move a millimetre outside what is written because you are out of the protocol”.

“We are not using that. We are tailoring our treatment to every patient based on the circumstances,” he said.

“That’s a big, big issue. And nobody seems to understand that we are not in the protocol world. We understand that, but we rather prefer to take every single child according to their particular circumstance.“

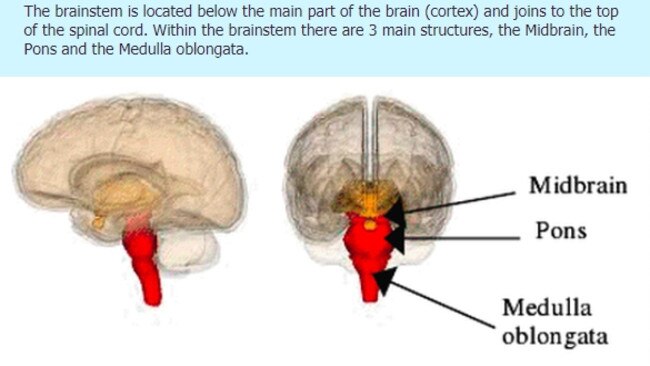

Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma’s (DIPG) are malignant tumours in the middle of the brain stem. Because they grow among many of the body’s most vital nerves, surgical removal is rarely possible because it could do more damage.

The tumours are aggressive and there is no standard chemotherapy available to treat them in Australia.

They are the second most common type of primary, high-grade brain tumour in kids, and when diagnosed, patients are usually told they can expect to live an average of nine months.

Usual treatment is a course of radiation, limited access to clinical trials and steroids to help with inflammation, but the cancer is considered incurable.

Dr Siller and Dr Garcia say they have given their treatment of targeted chemotherapy through the blood supply to the brain stem, as well as immunotherapy and steroids, to 70 patients.

Of those, 14 have died. The doctors say 10 of these patients died because they had accepted them when they were already too unwell from the cancer.

They said all of their drugs are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration but that they were constantly tailoring different drug combinations for their patients.

The doctors said they planned to released preliminary research in coming months and had not done so yet because they had not had time to do so.

PARENTS SAY THEY’LL DO ANYTHING TO SAVE THEIR DYING CHILDREN

ASK the parents who have defied their doctors and thrown everything at Monterrey’s last chance clinic whether they have any regrets and they point to their laughing, playing children as living proof they did the right thing.

Three Australian families credit the controversial Clinica 0-19 in northern Mexico with keeping their children alive in the past year, using a treatment they are begging Aussie doctors to trial at home.

It’s cost their lifesavings, they’ve had to sell homes and fundraise almost full-time to pay up to $30,000 a pop for the treatments, and they have spent months living away from their families in a country where they don’t speak the language.

Some have also faced pressure “pretty much the whole way” from their Australian oncology teams, who warn they are being scammed by dodgy “third-world” doctors using bad science to treat their incurable brain tumours.

None of the families believe the clinic is curing their children’s cancer and the doctors don’t claim to be doing so.

Instead, they say they are buying time, and that it’s priceless.

MEET THE CHILDREN WITH DIPG WHO HAVE FOUND HOPE IN MEXICO

As Annabelle Nguyen, five, and her friend Annabelle Potts, four, huddled together playing in the afternoon sunlight last week, their parents were mystified that anyone would try to stop them from chasing even the thinnest sliver of hope.

“When they say there is nothing they can do and that you just have to accept it, what do they expect you to do?” asked Canberra carpenter Adam Potts.

The two Annabelles and Melbourne’s Riaa Kulkarni, seven, are among 56 families from around the world being treated by Mexican doctors Alberto Siller and Alberto Garcia for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma (DIPG), an incurable cancer of the brain stem that usually kills within a year.

The three families were given the devastating diagnosis the same way.

“Basically the doctors take you into a little room and hand you a box of tissues and then start talking,” Annabelle Nguyen’s mum Sandy, from Perth, said, as Adam Potts nodded along.

“Everyone we meet here says the same thing, everyone was told with the box of tissues.

“They tell you it’s DIPG and they can offer a course of radiation. But then they just tell you go home and make memories, there is nothing we can do.”

The parents of both Annabelles said they had asked their doctors for information about access to trials in Australia or overseas.

“I was begging them, do you know of any trials after the radiation?” said Mrs Nguyen.

It wasn’t until she came across the Monterrey clinic on the internet and made contact with other families there that she considered it as an option, and the family moved over in May last year.

Riaa’s father Vivek said his daughter was initially accepted into a clinical trial in Australia, but that it hadn’t been effective for her after her diagnosis in August 2016.

“She started the trial and in four treatments she was not really responding, so we approached Dr Charlie Teo and he agreed to try to take the tumour out,” he said.

DIPG tumours nest in the centre of the brain stem called the pons, which holds most of the body’s vital nerves, so surgery is rarely used in case it causes more damage.

“Riaa was well for six months after the surgery but at the end of June she lost the ability to stand and her eye turned,” Mr Kulkarni said.

Mr Kulkarni had already been talking to other DIPG families being treated in Mexico, and by August, when doctors told him Riaa was nearing the end of her life, he took her to Monterrey.

“I took the plunge and came there, and now she is quite stable,” he said.

Riaa’s tumour reduced 40 per cent after one treatment and she is attending school in Melbourne, with visits every six weeks to Monterrey.

“All in all, it has been a good experience for us,” Mr Kulkarni said.

“I can completely understand where the Australian doctors are coming from, that they can’t support the lack of clinical trials and the scientific evidence that this works.

“Initially they thought we were being taken a ride, but now they have conceded to me that our daughter’s tumour is much improved and they can’t give me another explanation why.”

Like most of the DIPG families in Mexico, Mrs Nguyen would much prefer to be at home with her family than living in a cramped Monterrey apartment.

“We are frustrated that we can’t do this in Australia,” she said.

“But then, I mean we had no choice. If they have got nothing, they’ve got nothing.”

Kathy Potts, whose daughter has started ballet and pre-school despite being told she would not live through another Christmas, said their Australian doctors were disapproving of the family’s choice to pursue the Mexican option in June last year.

“Now the doctors in Australia have confirmed her tumour definitely looks smaller,” Mrs Potts said.

Annabelle was in Mexico last week for her 70th scan, an MRI followed by a PET-CT scan the doctors were using to examine separate swelling in her brain.

“The doctors in Australia said they didn’t know what the swelling was and we asked if they wanted to see the scans from Mexico and they said no, don’t even worry. They don’t agree with the scans they have,” she said.

“That’s why she has gone back to Mexico, because the doctors here in Australia said there was nothing they can do.”

On Thursday, the clinic said their scans showed Annabelle’s tumour was dead and described her as having “no evidence of disease (NED)”, which her parents described as “surreal”.

“We are very happy because at the very least it is going to buy us more time with Annabelle,” Adam Potts said.

“We are still very cautious though as these tumours can come back very aggressively. We have followed other children who been NED then out from nowhere died.

“Clinically Annabelle is perfect and we are very grateful to have her that way considering in other kids.”

CALLS FOR FUNDING FOR FAMILIES

A Senate report late last year called for more funding for rare cancers and for state governments to fund travel and living expenses for families who travel to take part in clinical trials.

The Mexican clinic says it being inundated with families from around the world. In the two days News Corp Australia was there, two new patients arrived, one from Sweden and another from the United States.

Greek schoolboy Christoforos Konstantopoulos has been in Monterrey since June last year. His family sped to the clinic just weeks after his initial diagnosis when doctors in Athens told them there was no hope for their boy.

“You don’t know what you are going to do when something like this happens, but the alternative was unthinkable,” his father Kostas said last week.

“His tumour has reduced 25 per cent now, and for us, this is as close to a miracle as we could have hoped.”

You can help donate to the families through the following links:

Email: sarah.blake@news.com.au

Twitter: @sarahblakemedia

Originally published as Inside the Mexican clinic defying Aussie doctors and saving our kids