High risk breast implants identified as cancer cases surge

AUSTRALIAN women were never warned that breast implants could be linked to a rare cancer, and the rate of the disease is surging as 40,000 people line up for the surgery each year.

Illness

Don't miss out on the headlines from Illness. Followed categories will be added to My News.

EXCLUSIVE

CANCER cases linked to breast implants have surged by an alarming 56.5 per cent in the last 18 months with 72 Australian women now contracting the rare disease and three dying from it.

As the cases mount victims have slammed the medical device companies behind the implants for refusing to pay compensation for the $6000-$10,000 corrective surgery they need.

Many of the women fitted with the devices linked to cancer had them put in after a mastectomy to treat breast cancer and are now tragically facing a second cancer scare.

TODAY, NEWS CORP BEGINS A CAMPAIGN TO:

* Require the companies that manufacture the implants linked to cancer to cover the cost of removing them when women develop the cancer;

* Demand state and federal governments make reporting of the implants used in each breast procedure to the Australian Breast Device Registry mandatory;

* Require all cosmetic and plastic surgeons to check women with high risk breast implants for cancer every 12 months;

* Require all breast device companies to declare publicly any payments or discounts they provide to plastic and cosmetic surgeons;

* Require all breast implant manufacturers to supply their sales data to researchers so cancer incidence rates can be determined.

MORE: Breast Cancer Network Australia turns 20

MORE: Women with metastatic breast cancer to get subsidy for two lifesaving pills

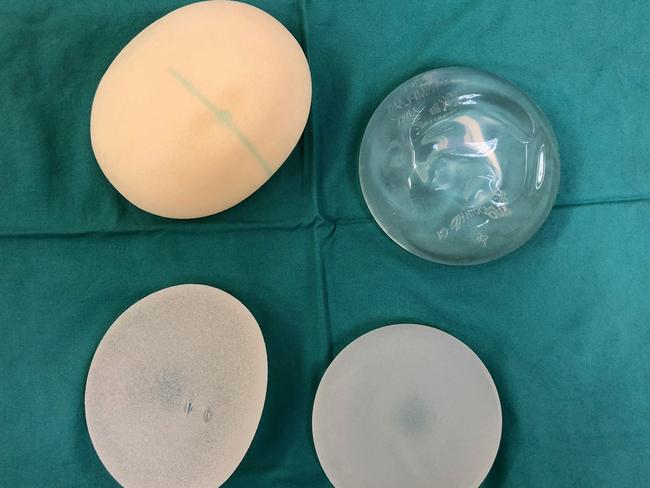

Macquarie University plastic surgeon Professor Anand Deva and Associate Professor Mark Magnusson say roughly half the more than 20,000 women a year who had a breast implant in Australia 2010-2015 were fitted with rough textured Biocell devices made by Allergan and polyurethane implants made by Silimed that have a much higher risk of the cancer.

Their new research shows risk of developing the cancer is 23.4 times higher for women fitted with the rough textured Silimed implant and 16.5 times higher for women with a Biocell implant compared to those who have a smoother Siltex implant.

Along with Brazil, Australia has the highest use of these implants in the world.

Five cancer clusters have been identified around Australia — and they’ve been linked directly to providers offering cheap breast implants who get the implants at discounted prices.

Prof Deva and Magnusson’s risk calculations — despite being cited by America’s medical regulator the Food and Drug Administration — have been challenged by the Australasian College of Cosmetic Surgery.

“Two years ago a Macquarie University research group claimed the risk of BIA-ALCL was higher with one type of implant from Silimed,” ACCS Chief Censor Dr Patrick Tansley said.

“Subsequent detailed analysis of their data by the College and others showed that claim to be substantially incorrect.

“It remains to be seen if their latest findings are correct, and given their previous incorrect analysis, further investigation will need to occur.”

Professor Deva says there are problems with his data because not every company provides sales data but he will keep updating it every year.

The national medical watchdog, the Therapeutic Goods Administration, is refusing to ban the higher risk implants but has convened an expert panel to advise it on the devices.

The TGA says women fitted with them do not need regular screening to detect cancer.

Instead it says it’s up to the surgeon to discuss the risks and benefits of each implant type with patients.

The Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons has backed News Corp’s call for the government to make it mandatory for surgeons to report every implant they use to a new Breast Implant Registry currently used by only three in four of Australia’s plastic and cosmetic surgeons.

“Everyone needs to participate in the breast device registry so we can get accurate data on this,” said Professor Mark Ashton, President of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons.

The Medical Technology Association of Australia, the peak body representing medical device companies, said there are other ways to record medical devices besides registries.

“We would support measures to enhance the coverage of registries but they are complex and expensive,” a spokesman said.

“Ultimately, there is a capacity for My Health Record to undertake a registry function and collect a significant amount of device and outcomes data in one centralised location.”

However, Professor Deva says it’s time all plastic and cosmetic surgeons declared the kickbacks, payments and sicounts they receive from device manufacturers that influence the which devices they recommend to women.

“The medical device industry in the US has an open payments system, I think we need that in Australia,” he said.

The cancer associated with the breast implants is not breast cancer but anaplastic large cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL) a form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a cancer of the immune system.

Half the cases of the cancer will develop within 7.5 years of the implant and 90 per cent will occur within 14 years.

Prof Deva whose research has tracked risk rates of the cancer says he fears even more women will fall victim in coming years.

This is because many of the discount breast implant providers who operated on thousands of women used the higher risk rougher textured Biocell implants.

Prof Deva’s research — into two decades of breast implant surgery — suggests bacteria floating in the fluid around breast implants is the cause of the cancer that develops in women with breast implants, however there are several other theories about what causes the cancer linked to the implants.

Women should not be alarmed about the cancer risk because most of the cancer cases identified are indolent stage 1a cancers, he said.

When detected early the cancer can be treated by removing the breast implant and the capsule surrounding it and no chemotherapy or radiotherapy is needed.

“Eighty per cent of the cancers are indolent disease, it’s like basal cell skin cancer,” he said.

However, if the cancer spreads more aggressive treatment is needed.

In February Australian cosmetic surgeon Dr Daniel Fleming published information on two cases of ALCL one of which spontaneously resolved and another which regressed.

While he says all women with ALCL should have the implants removed he notes:

“At least two types of BIA-ALCL appear to exist — non-invasive seroma-only disease that typically spontaneously resolves or remains indolent and a much rarer invasive malignant disease, usually with a mass present at diagnosis, which does not.”

All four recorded deaths in Australia and New Zealand were linked to textured breast implants.

There are two other implants not included in the study a polyurethane implant made by Polytech and another made by Nagor.

There is one case of ALCL in the world linked to the Polytech implant and five cases in Australia associated with the Nagor implant.

Worldwide around 500 cases of the ALCL cancer have been linked to breast implants and there have been 16 deaths.

But there are concerns the full picture is being hidden with many medicos unaware of the cancer and failing to test for it and others not reporting it because they fear legal action.

All the cases in the research have all occurred since 2007.

STACEY FRANKS NSW 50-YEAR-OLD NURSE

Stacey Franks’ 50th birthday present was meant to be a long awaited trip to New York, instead she got a gift she didn’t want — a diagnosis of cancer linked to her breast implants.

Last month, 10 years after she had rough textured Allergan breast implants implanted, her left breast swelled to double its size, was tight, hard and sore.

An ultrasound confirmed the implant had ruptured and a local surgeon who was preparing to remove it warned her he would need to test the fluid around the implant for cancer.

“I didn’t know what he was talking about, I’d never heard of cancer linked to breast implants, I don’t recall being told anything about it when they were put in”she said.

“There was no suggestion I needed regular check-ups or surveillance for cancer and none of my friends with breast implants had surveillance either,” says the mother-of-two from Sydney’s Collaroy.

Eight days after the operation to remove the implants Stacey was told tests on the fluid around them were positive for a lymphoma called ALCL.

She had a PET scan to see if the cancer had spread, it hadn’t.

Stacey has refused to have new implants put in and says “vanity is not worth it”.

“If I was told as a 40-year-old woman with two children that I had a one in 2000 chance of cancer I would never have got implants in the first place,” she said.

Stacey says it cost her $7700 in out of pocket medical expenses not covered by her health fund or Medicare to have the implants removed and tested.

She also had to take six weeks off work and lost the $2000 deposit she put on her birthday holiday to New York.

“We definitely need to ban these implants, we should just allow the smooth implants not linked to cancer,” she said.

Ms Franks said she feels the plastic surgery profession is more about money than the health of patients.

“The original surgeon was all about the money, as soon as he got the money he didn’t want to see me again,” she said.

“It was definitely a superficial production line.”