Inside the spiralling wait times for ADHD diagnosis

The Roumbos family are part of a rise of Australian parents trapped in limbo. Here they share how tough their reality is.

Neurodivergence

Don't miss out on the headlines from Neurodivergence. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Janelle Roumbos and her husband Nick are like any other South Australian parents raising children.

They both work, they are time poor, and like many families impacted by the cost-of-living crisis, they are trying to manage as best they can financially.

But Janelle and her husband feel a sense of hopelessness when it comes to their five-year-old son Nathaniel (Nate).

About one-and-a-half years ago, Nick and Janelle’s 9-year-old daughter Savannah was diagnosed with ADHD and autism level 3.

Savannah spent just under 18 months on a public health wait list for a developmental assessment.

“We noticed Savannah was late to develop,” Janelle says. “She was very delayed with talking, walking and other milestones that other children her age were quite fluent with. As bad as this sounds, she just seemed different to the other kids her age.

“She had a lot of trouble making friends because she would scare them off with her behaviour. In the classroom, she would often get up and walk around, fiddling with things while all the other students were sitting on the floor listening to the teacher.

“She also used to have meltdowns in the classroom and throw chairs, hide under desks and scare all the other kids.”

Since her diagnosis, Savannah has been able to access ongoing specialised support at school, allowing her to become more confident, social and independent.

While Janelle is grateful for Savannah’s turn around, she also feels a sense of guilt.

“It really breaks my heart knowing Savannah really should have had the help she needed a lot earlier,” the 34-year-old mother of two says.

“But the system is completely f****d right now.”

It’s a jarring response, emotive, powerful, the only expletive used in our conversation by the otherwise softly spoken mother.

It’s an emotional response, one coming from a place of sheer frustration as Australians face extremely lengthy wait times for mental health diagnosis and behavioural assessments, especially for children.

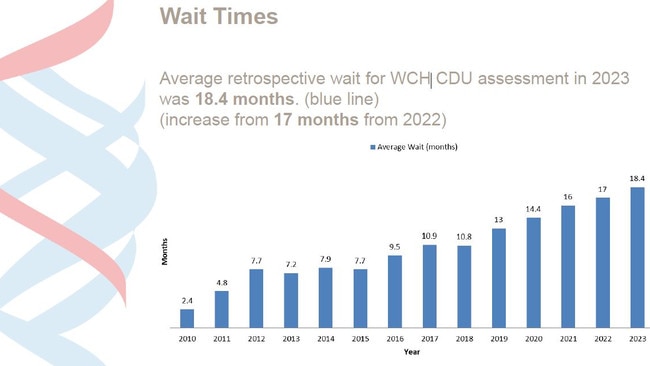

A 2023 report by the Women’s and Children’s Child Development Units (CDU) in Adelaide shows a child referred to the department for a developmental assessment is expected to be on the waitlist for over two-and-a-half years.

The assessment is critical because without a diagnosis, children and their schools cannot access funding for early education support.

For Janelle and Nick, there’s now a sense of dejavu as their 5-year-old son Nate - who was placed on Adelaide’s Lyell McEwin CDU waitlist in October 2023 - waits for a behavioural assessment.

Janelle says she was told it would be an approximate three-year wait, meaning they won’t have any answers until late 2026.

“We noticed Nate was quite delayed with walking and talking properly and a few other developmental delays,” Janelle says, noticing similarities in some of the behaviours and developmental milestones between her two children.

But unlike Savannah, Nate’s inability to regulate his emotions is more acute and for the Roumbos family, it is affecting everything.

The family now lives in limbo waiting for an assessment, while finding even the most basic tasks a challenge.

They are unable to go to the supermarket, unable to visit family or friends and unable to access help for their child.

“I can’t take my son to the shops,” Janelle says. “He’ll run around, he’ll knock things off the shelf, he’ll scream, he’ll lay down flat on the ground and have a tantrum.

Nate’s behaviour has also become isolating for the family.

“I feel like I can’t really take him to anyone’s house, because he acts up,” Janelle says.

“He’s full on with his behaviours and hitting, he’s very destructive.”

I ask her what it’s like living with a child, who through no fault of their own, cannot regulate their emotions or behaviour.

“It’s overwhelming,” she says, simply.

A report by the Child and Adolescent Health Community of Practice (CAHCOP) – an SA Health department responsible for developing statewide services for children and adolescents in South Australia - warns the impact of delays to diagnoses and support in children is profound.

The report states that a failure of children to access a timely assessment and along with access to post diagnostic therapy, within the early intervention age range, increases the risk of “poorer outcomes over the [child’s] life”.

But child psychiatrist and Adelaide University Professor Jon Juredini is not so sure.

Head of both the university’s Paediatric Mental Health Training Unit and the Critical and Ethical Mental Health research group, he says early detection and treatment does not automatically lead to better outcomes.

“If you take a population of children, all of whom meet the criteria for ADHD, there’s Australian research which shows that children who are diagnosed and treated do no better than those who are not diagnosed and treated,” he says.

“In fact, they may do worse. So, it’s not open to us to say that detection of these problems leads to better outcomes. It’s counterintuitive, but unfortunately, that’s what the science tells us.”

While the long-term impacts may be disputed, what is clear is that there has been significant growth in demand for ASD/ADHD assessments over the last decade.

But the 2021 CAHCOP report noted that “current and future service delivery issues … cannot be facilitated within contemporary funding parameters”.

Sadly, four years later, the same concerns are being echoed.

Documents from the Women’s and Children’s Governing Board, obtained under Freedom of Information, show all of South Australia’s CDUs continued to experience a steady increase in the number of referrals for assessments year-on-year, “without increased investment in

specialised FTE to keep up with demand”.

An internal SA Health report in 2023, reviewing the Women’s and Children’s CDU, states the last major workforce increase occurred in 2010.

While there are likely a number of factors driving up demand for assessments, the result has been a blowout in wait times, with the Women’s and Children’s CDU reporting an operational capacity to perform 451 assessments per year while accepting 1237 referrals in 2023 - a 42 per cent increase over 2022.

In 2024, an internal briefing to SA Health CEO’s, showed the Women’s and Children’s CDU needs to achieve 843 assessments per year in order to reduce wait times to 12 months - nearly double its current capacity.

The same document reports that the Women’s and Children’s CDU was at breaking point, having “exhausted available service improvement measures without compromise to service aims, throughput and clinical outcomes”.

Similarly, the Southern Adelaide Local Health Network received around 400 new referrals per annum with a current capacity to process 150.

And data provided by SA Health in February 2025 shows there are currently over 4000 children on the waitlist in South Australia alone.

Professor Juredini says the explosion in wait times speaks to a broader issue surrounding autism diagnosis.

He believes the system is being clogged by people who are displaying “milder and milder disturbances of functioning, which are being labelled as medical conditions”.

The result, he says, is that “people with more severe affections are not getting the attention they deserve.”

Shadow Minister for Social Services Tim Whetstone agrees, adding “No family should have to wait Two-and-a-half years for the answers they need to support their children.

“Labor has been all talk and no action when it comes to improving outcomes for children with Autism.

“Healthcare workers have been pleading for additional resources to ease the wait list, but even they are waiting for support.”

“We are calling for the Government to properly fund CDUs so no family needs to wait any longer than necessary for answers.”

It is perhaps unfair to lay the blame of the present situation directly at the feet of the current Health Minister Chris Picton.

The increase in wait times and lack of resourcing has been an ongoing issue which successive governments, both Labor and Liberal, have presided over.

Mr Picton insists the current government has been working to improve the overall situation, making it easier for children with complex needs to access specialist care within the public system.

“SA Health is aligning the models of care so there is equitable access to services no matter where a family lives,” he says.

Perhaps in recognition of the situation, the government also appointed a Minister for Autism, Emily Bourke, which Mr Picton says shows the government’s commitment to improving inclusivity for the autistic community.

Ms Burke set up the Autism Assessment and Diagnosis Advisory Group, which met in January, bringing together experts to help identify problems and opportunities for reform.

“We’re leading the country in these efforts, bringing the right people to the same table to address the barriers – with the Office for Autism, SA Health and Department for Education working together to support our most vulnerable kids and help them get an assessment,” she says.

Mr Picton also pointed to new programs being trialled by the government such as an autism assessment in schools program “that will see up to 100 students, including children on the CDU waitlist, access an assessment at no cost over the next two years”.

“This will not only get kids off the CDU waitlist but will support some of our most vulnerable kids in SA,” he says.

But in the end, its parents, like the Roumbos, who are left in limbo and it impacts everything for the family, including Janelle’s career.

While her employer has been accommodating, Janelle worries about her job.

“I’m restricted because I can’t work as much as I’d like to,” she says.

“I’d love to pick up a couple of extra shifts and some more money, but I can’t commit to anything because I’m not sure how Nate’s going to be at school.”

None of this is to say Nate is a bad child.

His behaviour may be nothing more than a neurological condition and like Savannah, he might just need some support.

Unfortunately, that is years away.

.

More Coverage

Originally published as Inside the spiralling wait times for ADHD diagnosis