Australian boxer Harry Garside on finding meaning after shattering Olympics loss

Australian boxer Harry Garside is on a mission to find meaning, as he revisits his messy night in his room after his Olympics dream was shattered.

Celebrity Life

Don't miss out on the headlines from Celebrity Life. Followed categories will be added to My News.

After pouring his shattered heart out in his post-Olympics interview, Harry Garside returned to his humble room in Paris which was clad with ‘I’m a gold medallist’ posters and photos.

The messaging, plastered in the lead-up as motivation, was a wicked reminder of what the larger-than-life Australian boxer had been fighting years for, and what he had just lost in a mere nine minutes after the first round of the mens 63.5kg class.

Unashamed of his theatrics, Garside admits he stormed into his room and tore everything from the walls, like a banshee let loose.

“I just remember wanting to be by myself. I never drink after big moments, so I chose not to drink. I just wanted to feel it all,” he says.

“I got back to my room and just started tearing everything down. I know it sounds a bit dramatic … I had this drink bottle with ‘I’m an Olympic gold medallist’ and I remember throwing that away too.

“It was a tantrum. It was definitely a tantrum. But I was like, ‘just let it out’.”

Fitting then, that someone so unafraid to wear his heart on his sleeve, to the point where he repeatedly apologised for letting his nation down, is joining the fight in breaking down the taboo of men’s mental health.

Garside, 27, is the latest ambassador for Top Blokes Foundation, an Australian youth mental health charity with evidence based programs in schools which encourage young men to be their authentic selves.

It’s an imperative initiative, with approximately 75 per cent of suicides in Australia in young males or men, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Garside’s candidness in a world which can be deeply consumed by perfect appearances has real potential to defy fears it’s weak to admit when things aren’t OK.

In perhaps his most self-aware, utterly human admission, Garside says his identity was so wrapped in what he did for a living fresh from his gold medal win at the 2018 Commonwealth Games, he would feel cut when he’d go out in public and wasn’t recognised.

“I would a hundred per cent recognise inside myself, there is an egomaniac, for sure,” he says.

“I wouldn’t have gone to Olympics if there wasn’t, but I think years ago, it’s like I needed it [attention]. I really needed, it consumed my whole soul and I felt really poor when I didn’t get it.

“I’m not ashamed of this, but I would go into a shopping centre, and if in my local area where a lot of people know each other, if I didn’t get recognised, I would feel quite sad.

“It sounds a little bit cringe, but that is because I was just sitting in my ego stage of that, my whole identity, that was me. It was like ‘recognise me, tap me on the back’.

“Maybe it’s because I’m getting older now, and I’m quite happy with the man that I am, always growing, always evolving, but if the whole world didn’t know my name, I don’t think I would care anymore.

“I’ve got to a place where a few people in Australia know my name, and it’s not as good as what everyone thinks. Nothing really changes.

“I’m still an insecure little boy at times. I’m also a super capable and strong man at times, but that all happens whether people know me or don’t know me.”

All of that to say, Garside says in our purest form, we all need connection, and that can only come from sincerity, no matter how “cringe”.

“We all feel emotions throughout different stages of our life, and when we talk about our experience and how an experience made us feel – highs and lows of our life and times, but then also grief, sadness and heartbreak – when we talk about it, we can all relate,” he says.

“Because we can all think about times in our life where we’ve experienced that, which is why I’ve always been an advocate for talking, because I think I’ve just got a manic crazy mind and I feel way better when I allow myself to get the nutrients of that out into the world and navigate that.”

The Tokyo 2020 Olympics bronze-medallist concedes he’s one of the lucky ones. Perhaps it’s just hardwired in him, but he’s never struggled to be vulnerable.

His exposure to suicide ideation came when his older brother was admitted to a psych ward as a teenager when Garside was aged seven.

“My brother had always been a bit of a dark sheep, and I just remember noticing that I recognised myself in my brother a lot,” he says.

“I don’t fully know if I understood what was going on at the time, but I do recognise that I was scared.

“And then throughout my childhood, probably more my teenage years, there was a couple of guys at the boxing gym that unfortunately took their own life.

“You know, I’ve taught myself to be an optimist, but I’m pessimistic by nature. I think we all are. But I have really taught myself to be optimistic, and I look out at the world most days, not all days, and I think, we live in the best country on earth. We have so many opportunities and I’m so grateful for that.

“But I can still recognise that there’s so many people that don’t see what I see, and I want to try and change that for many other people in Australia.”

Garside is now calling Sydney home after growing up in the small town of Lilydale, Victoria.

He fell into boxing aged 9, an unexpected pastime for an admittedly scrawny kid who was picked on at school for his “feminine” attributes.

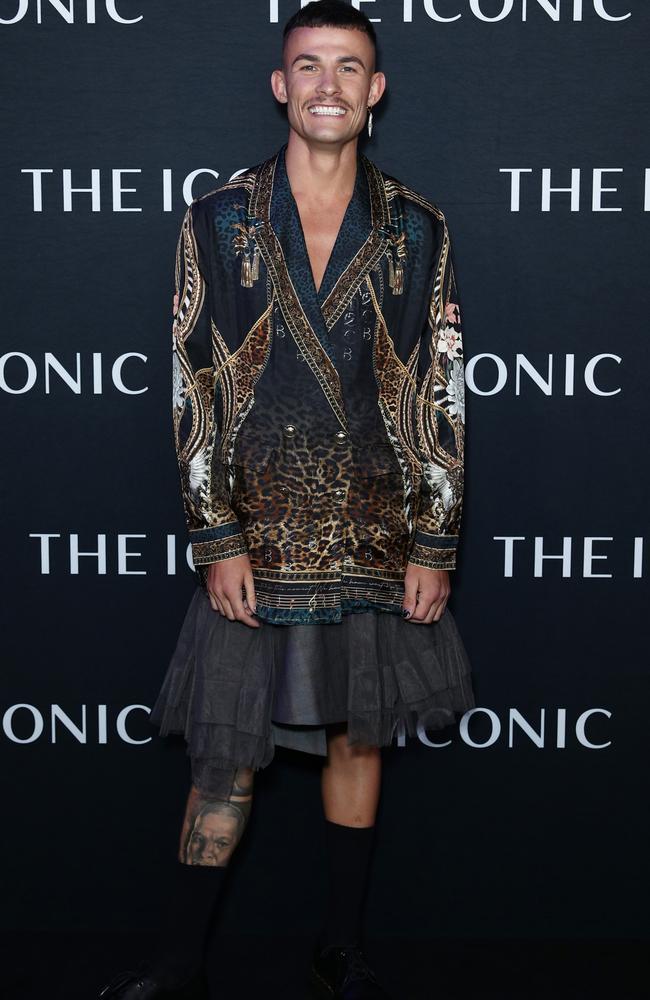

It’s those attributes Garside now uses as a tool to break gender norms, the boxer often becoming a talking point for wearing nail polish during his fights and rocking skirts at red carpet events.

Garside is straight, but he questions, why should that fit just one mould?

“At a young age especially, we’re not set in concrete, we’re just a little bit more open to exploring things, and as a society, we should be giving young people spaces where they can just explore themselves,” he says.

“They probably won’t find out the answers, I’m 27, and I’m still working out the answers, but I’d love if we could move towards the direction of [encouraging] self exploration.

“For me, it’s not about whether you’re a man, woman, boy, girl, LGBTQ+, whatever it is for you, as long you’re being yourself, that should be all that matters.”

As for how that message can be better spread, Garside believes emotional intelligence should be taught in schools.

Who needs to learn about the “United States president” when you can just Google it, he jokes.

“But seriously,” he continues. “Imagine a school where it fostered young people understanding what they felt like when they threw a ball, or when someone said a hurtful comment, how did they feel? And how did that person feel when they said that hurtful comment? Just genuine self exploration, all the time,” he says.

“Obviously you need to focus on English and maths and all those other things, but a good portion of the day focused on that sort of stuff too.”

He pauses momentarily, before being struck with more ideas.

“And imagine leaving school and that doesn’t end. There’s still weekly catch-ups where someone who’s 80 is with someone who’s 16, and they’re in the same room talking about their inner workings, and the person who’s 16 can learn from the person who’s 80.

“I don’t know, I just think we need to find ways to be more accepting of all people.”

Setting goals has long kept Garside on-track.

He sacrificed a professional career to train for his Olympics campaign, and after that came crumbling down, probably for the first time in his adult life, he doesn’t have a set purpose.

But a recent epiphany while sitting in his car told him maybe that wasn’t such a bad thing.

“It [the epiphany] was in this space of like 30 minutes. It was very quick, which was nice,” he says, laughing at himself.

“When you lose something, we always attribute that to a negative thing. As a kid, if you lose your teddy bear or you lose something, you lose your parents at the shops … We see it as negative.

“But on the other hand when you lose something, you have the ability to go on an adventure and find something.

“And I think I said to myself, the back end of this year, for me, is just all going to be about finding something.”

Originally published as Australian boxer Harry Garside on finding meaning after shattering Olympics loss