Reverend Bill Crews releases moving memoir Twelve Rules For Living A Better Life

In this sneak peek of his new book, Reverend Bill Crews reveals he was a regular guy with an office job — until an encounter changed his life.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

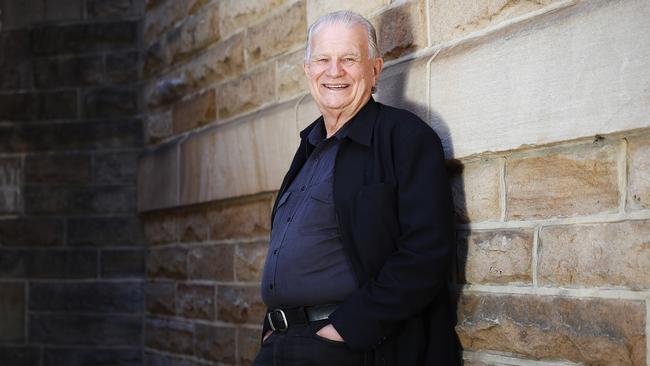

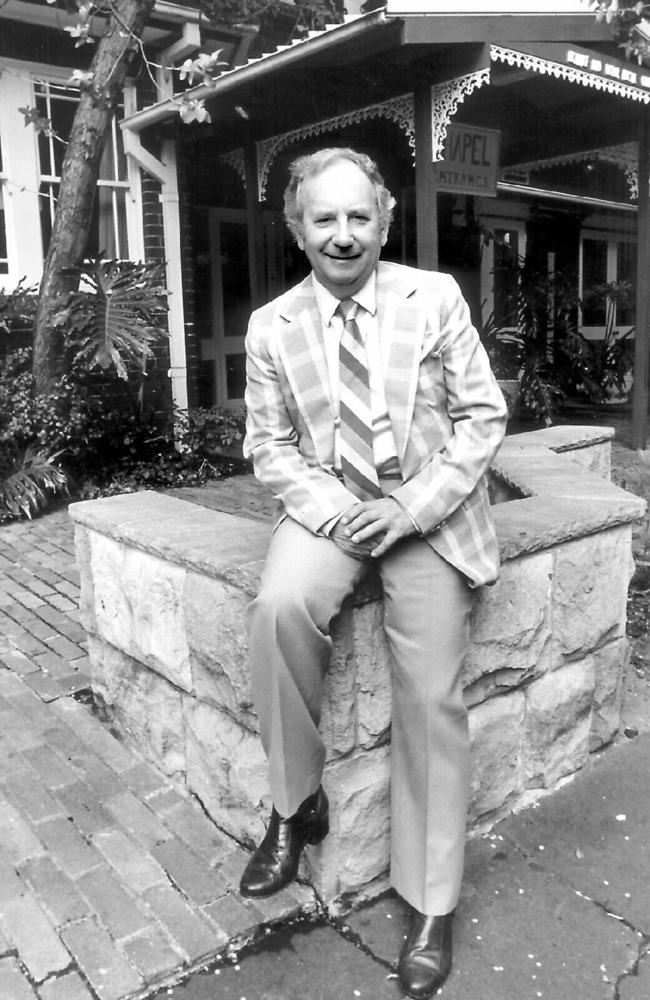

Reverend Bill Crews can barely look at his new book.

Sitting in his Ashfield office within the Bill Crews Foundation he’s spent his life creating, the Uniting Church Minister is uncomfortable talking about the man behind ‘Bill the Brand’.

Bill the Brand has strangers approach him every day, saying he’s changed them.

Bill the Brand has raised $70 million for people in need, fed over three million meals to the homeless and taught thousands of kids to read so they can break the poverty cycle.

Bill the Brand is one of Australia’s 100 National Living Treasures, and for good reason.

But Bill the man has been broken by heartbreak over his 76 years, being disowned by his parents, struggling to cope with two failed marriages, and up until 10 years ago, had strained relationships with his four children.

Scroll down to read an exclusive extract of his book.

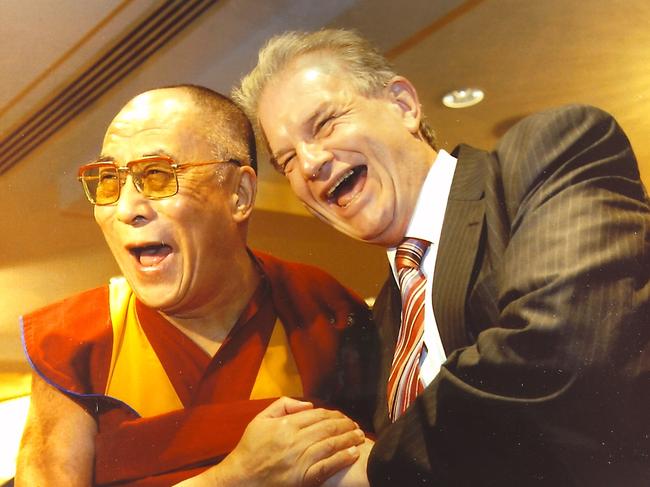

Bill the man counts the Dalai Lama and John Singleton among his closest friends.

He’s lonely. He’s vulnerable. And he’s grateful.

“That can either break you, or break you open,” he told Saturday Extra.

“And I hope with me, it broke me open.

“The Buddha says a broken heart is a beautiful thing because it learns compassion, so I can use that experience of what I feel in a compassionate way that improves and helps people in society.”

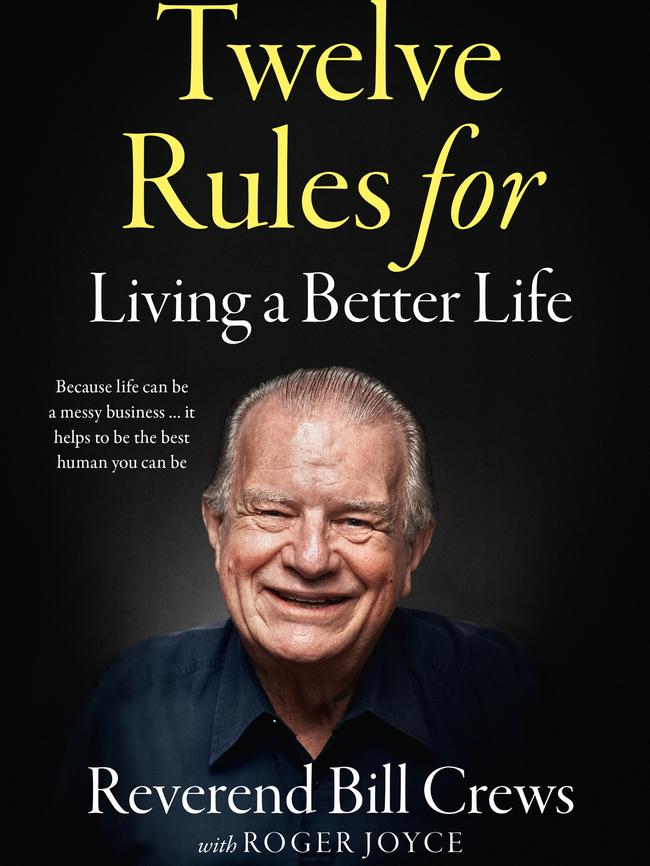

Crews has written Twelve Rules For Living A Better Life, a moving memoir which will be released by HarperCollins next month.

In it, he shares intimate insight into his private life as well as well-earned wisdom on how to be a better human, revealing the incredible highs – and lows – of his remarkable journey.

“I find it hard to read,” he admitted.

“I find it hard to look at … some of the bits in there are really painful.

“I’m much easier talking about Bill the Brand than talking about Bill the human being, but it forced me to look at my life as just a story.

“I can hold it intensely in, but when you read some of the other stories in life, it’s just one.

“I think if I’m really honest, I think that’s why I like Singo and the Dalai Lama so much, because I think they feel that loneliness too.

“Everyone has a story.”

Like the congregation he leads today, Crews grew up feeling like an outsider.

Unlike his younger brother Bob, Bill was a “dreamer” and his father wanted him to “toughen up”.

“While Bob was winning awards for his sporting prowess, I was reading, thinking and pondering,” his book reads.

“I would give my stuff away, and Dad would be angry with me … all in all, I felt I was a disappointment to him.

“I could never quite get a look in with my mother either. Dad dominated her, and what he said, went.

“With the birth of my sister, I felt even more like an outsider to the family.”

The family moved from St Marys to Riverstone and Townsville before returning to Sydney.

Being bullied in his school years, Crews says, made him a better person, with “real change only happening in excruciatingly painful situations”.

Despite the pain, he won a scholarship to study engineering at the University of NSW and got a cadetship with BHP to follow his father’s footsteps as an electrical engineer.

After the tragic death of his brother Bob in a car accident, the dynamics between he and his parents worsened.

He searched for guidance and “something more”, ending up in Kings Cross, where he would go to the Wayside Chapel, pastored by Reverend Ted Noffs.

“I was doing well … but I wasn’t happy,” the book reads.

“In some part of me I knew I was just following the part of my father, not finding my own way.”

He soon became a volunteer at the Chapel, and for the first time in his life, felt “at home”.

“They were all my brothers and sisters – the counsellors and the people in trouble were my family … this was my tribe.”

It was there in the 1970s that Crews heard the voice. An experience he describes as “a knowing”, which told him to leave his job and work at Wayside, helping the poorest of the poor.

The urging to change his life completely couldn’t be ignored.

“I just had to do it. I’ve always had a choice – but no choice,” Crews said.

“Forty years later in psychotherapy, I was saying ‘why me, why me, why me’ – and he said ‘because the voice knew he would carry it out’, and that’s true.”

His father disowned him and he became estranged from his family and most of his friends from his old life.

He had a son, Michael, with first wife Barbara, a woman he met at Wayside who abandoned the pair when Michael was two, devastating Crews.

He then met Gill, a helper at the chapel who “got into his soul”.

The couple wed and had daughters Emelia (Eme) and Alex, as well as son Tim.

But Gill soon got sick, and it was discovered the blood she had received prior to Eme’s birth was contaminated and she contracted hepatitis C.

The news made Crews agitate for a Senate inquiry into tainted blood, an issue that remains close to his heart. He and Gill were divorced in 2004 after 20 years of marriage.

Strained relationships with his children due to ‘life’ have improved in the last decade, all thanks to a lot of hard work and a gradual learning with therapy under his long-term psychologist Dr Bob Wotton and relationship expert Jon Graham.

He was also able to improve relations with his parents before they died.

“I have to remember to be grateful for the really warm relationships I have now and in a sense not mourn the past,” he said.

“I met Jon because I was having difficulty with some of the congregation and I needed to find ways of getting through and it was looking at that and realising that you don’t talk to a banker the way you talk to a physicist or to a philosopher – you if you want to get the same message across, you have to use different forms of words and different ways – and it stated to work.

“Then I thought, maybe there is a chance of rebuilding my relationships with my kids, and that took 10 years.

“You don’t know what you don’t know. What I’ve learned in life is everything changes everything.

“I might be talking to you and I might learn something which might relate with my family or whatever – so once I learned I could talk to bankers, I realised there are ways of talking to people.

“The other thing I learned is that love and compassion is really the way – and the difference between sympathy and empathy is really important, and taking the egocentrismout of it, which is hard to do.

“We will be sitting here and someone will say ‘I’ve had a terrible day’. Well the worst thing I could say is ‘I’ve had a worse day’ – but if I stay with that person, the magic starts to happen.

“And being able to stay with my kids in their pain, and put my pain aside, enabled that to happen.”

In 1986, with a theology degree from Sydney University, he was ordained a Minister and found himself at Ashfield, where his Foundation, a constant hive of activity, remains today.

“Honestly, when I went to Kings Cross I was 25, and I saw all these things with these kids and it was wrong,” he said.

“I just did what I thought any decent human being would do.

“Obviously, it hasn’t been enough because kids like that turn up here everyday and it’s sobering to realise that everything has changed but nothing’s changed.

“What I am trying to do is talk to people who can hear what I’m saying and want to do something.

“So many people want to do something but don’t know what to do. And they don’t realise that all they have to do is go out of their front door and whistle.”

He said half of it was showing up – the other half was following through.

“A lot of people have all the right attitude and things, they just don’t do anything with it,” he said.

“I asked a young fellow who works here what this place means to him – he said ‘everything’.

“And to me, that’s everything.”

READ AN EXTRACT OF BILL CREWS’ BOOK BELOW

In this exclusive edited extract from his book Twelve Rules For Living A Better Life, he tells how that experience came at an enormous cost.

In the early 1970s, the Wayside Chapel, situated in Sydney’s Kings Cross and pastored by the Reverend Ted Noffs, was the epicentre of the alternative culture movement. Sydney at that time had the largest hippy colony outside San Francisco and practically all of those hippies, along with Sydney’s poorest and neediest, spent a good deal of their time at the Wayside.

Kings Cross, aka ‘the Cross’, is a hop, skip and a jump away from Sydney’s centre. The gentrification of the Cross and its surrounding precincts of Potts Point and Elizabeth Bay has long been underway but the destitute, the celebrated, the homeless and the happening crowd somehow still mingle and get along in the Cross, not a stone’s throw from the famed Coca-Cola neon sign meeting point.

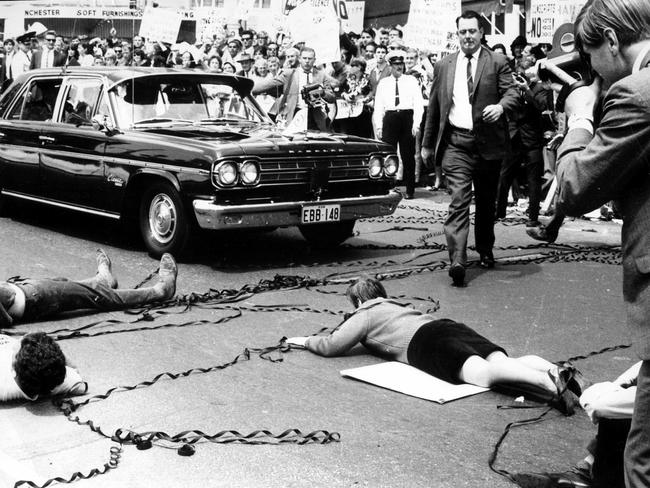

From that first time onwards, I went to the Wayside every night. At the Chapel’s Sunday evening services, I’d listen to various people who would talk about the social justice projects they were working on. But the highlight event at the Wayside Chapel was Sunday night’s Question Time, when, in the basement theatre, Reverend Ted would open himself up to questions from the congregation. There would be guest speakers like prominent biologist Charles Birch, evangelical minister Billy Graham, the leader of the Children of God, the leader of the Hare Krishnas, Prime Minister Gough Whitlam and John Singleton. I remember a group turning up all bloodied because they’d been at an anti-Vietnam War protest and the cops had beaten them up. Anyone could ask a question. It was a free-for-all. The debates between Ted, Webster and the visiting speakers were something to behold. Maybe because I was felt so much in chains at that time, they started me thinking about the idea of freedom.

I came from a relatively ‘normal’ middle-class home. It was not really religious at all. The only time I remember us all going to church was when my brother Bob died. I was blown away both by the bohemian atmosphere and the sheer need of the unfortunates approaching the Wayside Chapel for help. ‘If you’re not part of the solution, you’re part of the problem,’ said Ted, the charismatic pastor, the showman, dressed all in white – white suit, white shoes, white shirt, white tie – challenging the crowd.

I quickly decided that I did not wish my life to end with me feeling I had been part of the problem, and so volunteered to help. I’d volunteer in the coffee shop and on Saturdays I’d go and visit the old ladies in the neighbourhood who were being literally terrorised by property developers like Frank Theeman who wanted to tear down the Victorian terrace houses in the area and replace them with soulless, profit-turning high rises. I was caught up in all of that, and well remember the disappearance a few years later of Juanita Nielsen – an activist and local journalist who spoke out against Theeman’s plans and the eviction of dozens of residents from their homes on Victoria Street. It was an ugly time.

Very soon I wasn’t just listening to the Sunday service and the ensuing Question Time, I was helping run them, reading psalms, and when Ted started a crisis centre, I became part of that. It was a drop-in and call-in centre for people in trouble. As it grew, we were face-to-face with all the traumas experienced by people living in Kings Cross and elsewhere. The drugs, the sex, the Americans soldiers on R & R from Vietnam. The runaway kids. The corrupt police. And over and over, the drugs.

I was home. They were all my brothers and sisters. The counsellors and the people in trouble were my family. It was magic. We were a group, a tribe, and unlike Townsville Grammar or AWA (Amalgamated Wireless Australia, where I was working), this was my tribe.

As a volunteer at the Chapel, the first thing I was asked to do was drive the Chapel jeep somewhere. I’d never driven a four-wheel-drive before. But whoever was with me said it’s easy, just get in and drive it. I did, I drove it. It was the first time I realised I could do something capable and useful that wasn’t part of the path my parents wanted me to walk down. I had all these sides to me that had been blocked or imprisoned. I was full of abilities and competencies and stuff that my father thought wasn’t important, but most of my being had been submerged, pushed down. The Chapel showed me that there was more to me than met the eye. Ted Noffs was part of my opening up, and in many ways I looked on him like God. Or perhaps as a father.

Whether it was the combination of working with needy people and participating in the church services and seeing work through new eyes I’m not sure, but within a few weeks my visits to the Wayside Chapel led me to undergo a profound religious experience.

One evening, at the Chapel, I was going up the stairs to the coffee shop to do my shift and I got to the landing. It must have only been a millisecond in which all I’m about to tell you took place. Yet time seemed to stand still. I cannot say that I literally heard a voice, but it was a knowing and to this day I’ve spoken of it as a voice. It just happened as I paused momentarily on the landing. The ‘Voice’ said to me: ‘You are to leave your job and come and work here. You are to work with the poorest of the poor. The work will be hard and unrelenting, but I will be with you. The work will be onerous, but I will help you keep at it. I will guide you. You will become well known but don’t worry about that. And by the way your personal life won’t be that happy. But I will be with you.’

It was the last bit that made me realise it was real. If it had been all flowers and sunshine and happy music and I was told I would be happy forever and that I’d be rich, I wouldn’t have believed it. But because the good stuff, the success, was leavened with the not so good, that’s what made me believe, made me trust.

I have found that most people who have these sorts of experiences come from a fundamentalist Christian background and are confirmed in their prejudices and preconceptions by what they hear. My experience was almost the opposite, urging me to change my life completely and opening me up to a wide range of religious and spiritual thoughts and experiences. I embraced the multiplicity of religious and spiritual beliefs of the alternative culture as well as those that were more traditional, be they Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim, Jewish and so on.

Whatever had taken place going up those stairs, it was as if the sun had come out for me. Bang! Just do it.

I went to AWA the very next morning and said, I’ve got to leave; I have to go and work at the Wayside Chapel. I didn’t talk it over with anyone. It was difficult, because AWA had invested a lot of money in me, in my studies. I remember I was crying and upset. I just have to go, I have to go, I said. There was no looking back.

By comparison, telling AWA was the easy part, because then I had to go home and tell my parents. I had to tell my father. It was really hard, but I had no choice. I was turning my back on a promising career, a well-paid job I’d studied for, that others envied, a position Dad had gone out on a limb to get for me.

My father disowned me. It was terrible.

For the past fifty plus years I have in my own imperfect way tried to stay true to that Voice. In many ways I feel like the Apostle Paul who uses the word doulos to explain his relationship with God. Doulos means slave or servant. I know rationally I can walk away from the Church and my ministry at any time, but emotionally I can’t. Sometimes I wish to hell I could. I could have ignored or denied the Voice, but I didn’t. I could have stayed at AWA, but I didn’t. I could have made my father proud, but I didn’t. I now know I never could. Towards the end of his life, I could see he was proud of me but it seemed to be because I was well-known.

Twelve Rules For Living A Better Life by Reverend Bill Crews, published by HarperCollins Australia, is on sale from May 5. Pre-order at Booktopia.