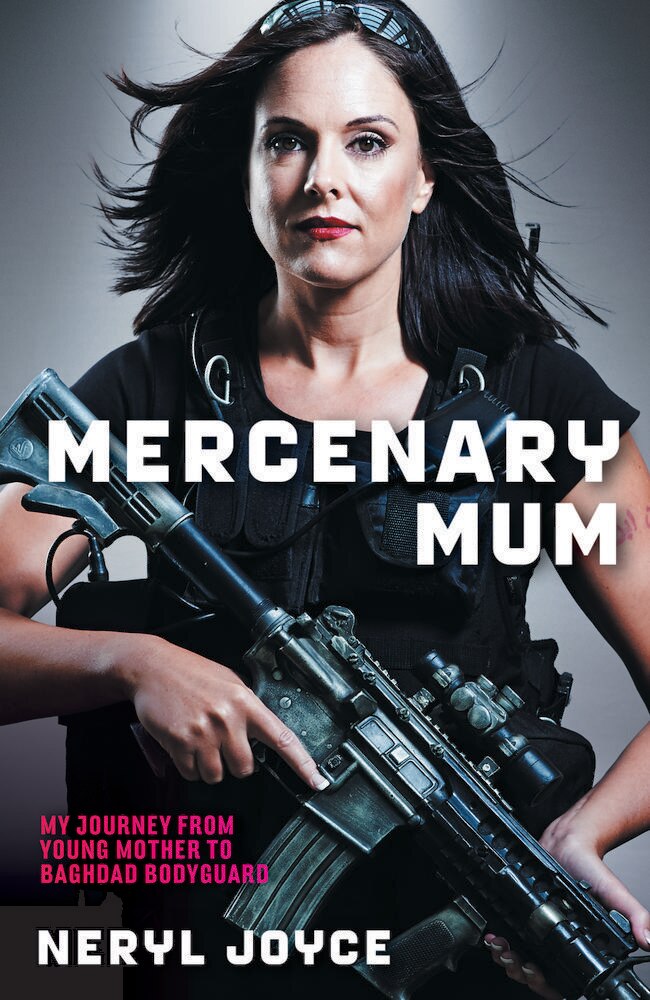

Neryl Joyce tells of her journey in her book Mercenary Mum

EXCLUSIVE EXTRACT: Australian Neryl Joyce went from being a single mum to a Baghdad bodyguard. But her journey exposed her to more than threats of ambush and assassination.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

NERYL Joyce went from single mum to a highly trained Baghdad bodyguard. But her journey from working at Woolies to protecting innocents in the battlefields of Iraq exposed her to more than threats of ambush and assassination – she had to battle with her own teammates as well. In Mercenary Mum Neryl reveals what she had to overcome in order to succeed as a woman, and a mother, in the dangerous world of high-risk security.

I love my dad. He was an army infantry officer who held himself to a high standard, and he expected the same of those around him. At age eighteen when it was time for me to leave home and start life on my own, he dropped me off at the train station. I was off to join the army, just like him.

My first job after graduating from recruitment training was as a dental assistant based at the Wagga Wagga Royal Australian Air Force base. The dental unit mainly involved packing and repacking medical stores. The days were long and boring. I needed something more than suction machines and dental floss to spike my interest and enthusiasm.

One day, the military police (MPs) came to our medical facility to give us a presentation on their roles in the field. I knew it was for me. As a woman in the army at that time, I wasn’t able to join combat-related corps. However, as an MP, I’d be able to see and do many things that most women in the reserves wouldn’t. My mind was made up: I was going to apply for a corps transfer to military police.

With my new career in the MP in my sights, I moved to Cairns to start a university degree. I got a part-time job at Woolworths and moved into a tiny unit. During my uni breaks, I would fly down to Brisbane for my MP training. I had to work hard to balance the demands of my studies with those of my job but I passed the MP course with flying colours. I was the top student and the only woman in the platoon.

It was around this time that I met Bruce, who was also in the army. We got engaged and, in due course, I became pregnant. I couldn’t wait to be a mum. We were going to be the perfect little family.

As the months went by, I no longer fitted into my camouflage army uniform and had to start wearing a maternity dress. I worked right up until I went into labour and when our baby was born we named him Kane – ‘son of the warrior’.

I really took to motherhood. There were nappies to be washed, feedings at all hours and limited sleep. But it was glorious. My maternity leave was all too short. I took extra leave without pay. That’s when things started to get tough financially. With great reluctance, I returned to work.

At the start of the new millennium, we moved to Canberra so that I could undertake officer training at the Royal Military College (RMC). I didn’t want to give up the chance to become an officer or give up being a mum. Somehow I juggled the two roles.

Officer training was definitely one of the most challenging times of my life. The days were long, and the nights longer. I’d escape the rigid training institution and return home to my son. I didn’t want Kane to forget who I was. Each night I bathed him, fed him and put him to sleep. As I lay with him to settle him down, I’d often fall asleep from exhaustion.

My alarm was set so I could work on my assignments before Kane woke up. At four in the morning it is hard to focus on the weapon characteristics of an Abrams tank as compared to those of a Leopard tank.

Eighteen months later my father looked on proudly as I received my commissioned rank of lieutenant at our graduation ceremony. It’s funny how when you’re on a good run you don’t stop to think that things can go wrong.

My relationship with Bruce had been put under considerable strain during my time at RMC and eventually Bruce opened up: “I’m leaving. I don’t love you anymore.” I was devastated – completely and utterly devastated. To top things off, I had to march into my new unit the very next morning.

The next day I dropped Kane off at day care, reported for duty, did my job, and then came home. That became my life: work, look after Kane, work, sleep. For the next year and a half, I struggled along. Bruce was hardly ever around as he was either deployed on operations or attending courses. I had no life outside of Kane. I wasn’t interested in going out and meeting anyone new. I wanted to concentrate on my son and make things the best I could for him.

In January 2003, I was given the opportunity to try out for the elite MP close personal protection (CPP) course. Only one or two officers were permitted to attend the course at a time, as most of the positions were given to the lower ranked corporals.

It was the best course I’d ever done: it was physically demanding, mentally draining, but a hell of a lot of fun! I was ecstatic when I learnt I had passed. I had worked hard and was extremely proud to be the first female officer qualified to command CPP teams on military operations.

As a female leader in the army, I found that I had to be above average in all areas of the job in order to be thought of as equal to my male counterparts. I needed to be ‘special’ in order to be accepted. Completing the CPP course bolstered my reputation as a female leader, and I hoped it would propel my career within the MP.

However, as my relationship with Bruce continued to deteriorate, work went off the rails.

My soldiers and sergeants were being deployed on operations, and I found myself left with an understaffed platoon for most of the year.

At first I relished all these challenges, but after twelve high-tempo months it just got plain hard. I loved my job, but being a single mum was tough. All too often I found myself driving Kane to my mum’s house at the weekend (a twenty-hour round trip), so I could attend mandatory army field exercises. I’d then have to repeat that trip the following weekend to pick him up.

I had got so much from being a soldier and an officer, but things had changed. At work, I wanted to invest all my time and effort in my job. When I was at home, I wanted to immerse myself in Kane’s life. As things stood, I wasn’t doing either to my satisfaction: my mind was always in two places. I also had a deep sense that I wanted something more out of life. So I began to think about other options.

I’d heard about the emerging security contractor scene in Iraq. My whole adult life I’d trained to work in a war zone, and yet I couldn’t do so as a female officer. But, in the security sector, the possibilities were limitless. I wrestled with how it would affect my son, and ruminated torturously on the ‘what if’ scenarios. How would Kane cope without me for six months – the length of the typical contract? What if something happened to me while I was over there? These were difficult, soul-searching questions.

After lengthy discussions with Bruce, we decided Kane would live with his dad for the six months I’d be away, and when I returned on leave I would be a stay-at-home mum. Apprehensively, I resigned from the army and, before I knew it, I had a job lined up as part of a private security detail (PSD). This was a life-changing decision, and making it felt electric.

After three days in transit I picked up my luggage from a broken-down conveyor belt at Baghdad airport and headed over to customs – and by ‘customs’, I mean a man sitting behind a small table. I took out my knives, weapon holsters, and chest webbing, but my kit barely roused the man’s interest; he simply waved me through. I smiled to myself.

Today was the start of my new career. I was a new member of the security team hired to

protect the nine Iraqi electoral commissioners.

It was strange how quickly living in a war zone became ordinary. The days were a strange

mix of being on intense alert, looking out for threats, and being profoundly bored. But death was never far from my mind.

One evening we turned into the street where three of our clients lived and were met immediately by US military forces. A mortar had landed right in the middle of the street, causing massive destruction. A guard had been hit in the neck by some shrapnel and a child who had been playing outside had also been hurt.

I noted a man running towards a small group of people who had gathered in the street. I looked closer only to see that he was covered in blood. I heard a great scream, followed by wailing. Several women, covered from head to toe in black, huddled together and began keening. The sorrowful howl grew louder and louder, and steadily more hysterical.

A US military interpreter went over to the women, but they were in no condition to talk.

The blood-soaked man told him that the little boy who had been playing outside when the mortar hit had died on the way to hospital.

Luckily our clients managed to escape the blast, but I could only imagine how those women felt. The pain must have been unbearable. I could feel it digging into my heart.

Life as the only woman in a security team isn’t without its challenges. Threats from attack were one thing but I also had to fight just to be recognized by my own team. In one instance I was told I would be used as the bodyguard who handled ‘female’ issues and that my fellow security contractor Smokey would be used as the ‘real’ bodyguard.

No matter how I phrased it, my team leader just couldn’t see what my problem was – why I would take issue with not being trusted to do my job, despite the indisputable fact I was the best qualified person on the team to do it. In the end I had to fall into line, as unhappy about the decision as I was.

I was getting really frustrated. I was used to the Australian Army. There, we worked as a team; we communicated and we helped each other out. This was not how they rolled here. No one was being trained properly, people were stepping into jobs they weren’t qualified to perform, and there was no group solidarity. I felt my professionalism was being compromised. How sad that my concerns would reveal themselves to be very well founded.

One morning my team headed out for Baghdad airport to pick up a client. I had injured myself and was unable to go with them. I think sometimes things happen for a reason.

On the way to their airport my team was ambushed on Route Irish, one of the deadliest roads in the world. My colleagues Tomahawk, Camel and Ronin were all shot and killed by insurgents and there was nothing I could do.

Insurgents were to blame for the deaths of my mates, but the team’s safety was the responsibility of my leaders and my company. Their failure has left me bitter and angry to this day. As a security team, we were supposed to avoid risk, and run our operations as safely as possible. It was blatantly obvious this was not happening, and it contributed to the deaths of my colleagues.

I couldn’t wait to leave the country. A few days later I caught a lift back with another team.

As we flew out of Iraq everything felt different. I didn’t have to watch my back anymore.

Gone were the guns, the armoured vehicles and the tang of testosterone in the air. I was heading back to civilisation and to my little boy Kane who I loved and missed so much.

It felt like I had lived a lifetime away from him. Now, I was returning to my son, and to being a mother.

Edited extract of Mercenary Mum by Neryl Joyce, published by Nero.

Originally published as Neryl Joyce tells of her journey in her book Mercenary Mum