Grantlee Kieza reveals man behind myth in Macquarie

Lachlan Macquarie is credited with shaping Australia’s destiny. But was he a reformer or a tyrant? In his book extract, Grantlee Kieza looks at the man behind the myth.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

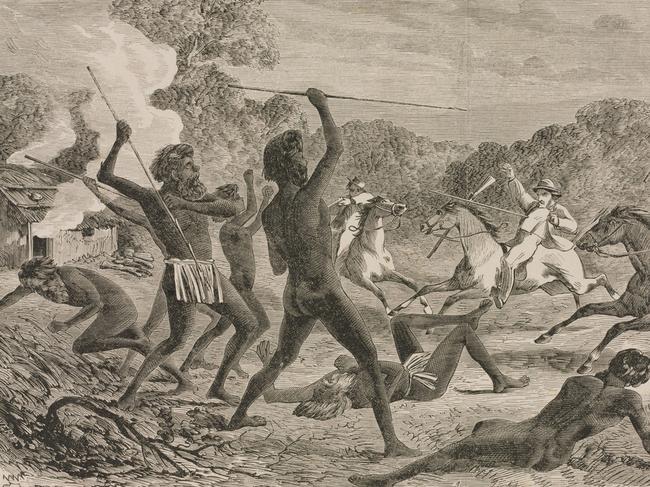

Lachlan Macquarie is credited with shaping Australia’s destiny, transforming a penal colony into a prosperous society. In this extract from his new book Macquarie, Grantlee Kieza asks whether he was the man who sowed the seeds of a great nation or a tyrant who destroyed Aboriginal resistance.

IT WAS A COLD, moonlit morning and the Cataract River flowed rapidly northwards from its source near Mount Pleasant in the Illawarra.

The deep water cascading over the boulders was caught in the stream, before rushing through the deep canyons. The mossy crags and thick forest carpeted the whole area in a sea of dense, dark foliage, ending in sheer cliffs 60 metres high.

The air was heavy with menace. There was no sound of an owl, no rustle of a kangaroo, no

lowing of cattle in the distance – just the burbles of the fast-flowing water, punctuated by

the thump of boots striking the rocky ground as the red-coated soldiers of the 46th

prepared to administer frontier justice.

The pocket-watch of Captain James Wallis had told him it was just after 1am when he

ordered the shadowy march from the camp at the Cowpastures to this spot. It was 17 April

1816, and Wallis had been hunting Aboriginal people in vain for a frustrating week. Now his

native guides had led him to this majestic campsite, shrouded in the soft moonglow.

The camps were deserted but their fires were still burning. Wallis, a talented artist and

ambitious young officer from Gloucestershire, crept forward to where he hoped the locals

were hiding. He feared that, knowing this country better than he did, his quarry had

escaped once again to make his pursuit look like a folly.

Then he heard a child cry.

At the same time Lachlan Macquarie slept at Government House beside his wife Elizabeth,

and their little son Lachlan Jr, the three-year-old’s long blond hair and rosy cheek resting

lightly on the pillow.

The Dharug people were much less comfortable as they tried to shelter amid the rugged

rocks and cliffs near Appin, knowing that their lives were in danger.

Macquarie’s foot soldiers were about to perpetually stain the governor’s record with the

blood of innocent men, women and children.

Macquarie had written a précis in his memo book on 10 April of the orders that he had

given to three officers. Their mission was to commence the next day.

He had resolved to send a grim warning to the native population of the colony. His

reputation for mercy was set aside. He wrote that he felt ‘compelled, from a paramount

sense of public duty’, to ‘chastise these hostile tribes’ by inflicting ‘terrible and exemplary

punishments’.

Macquarie might have been psychologically unhinged. Certainly, his health was in decline.

The years of heavy drinking, the syphilis medications he had taken and the enormous stress

of his battles with bureaucracy over his lenient treatment of pardoned convicts might all

have contributed to his 180-degree turn in relation to the indigenous people he had always

viewed with benign paternalism. His authority was being threatened by the Aboriginal raids

and as the leader of an army he was not going to let enemy forces gain the upper hand even

for a moment.

Once he had apologised for the Aboriginal attacks on settlers, saying it was mostly the fault

of the whites. Now, he would not be swayed by moderate voices.

Dr Charles Throsby, who had hosted Macquarie at his property Glenfield, counselled the

governor against reprisals.

MORE NEWS

The top ten most gripping non-fiction books

Top ten books for summer reading

Top ten kids’ books of the year revealed

On 5 April 1816, Throsby had written to Acting Provost-Marshall William Wentworth

expressing his concerns for the safety of Aboriginal men Yelloming and Bitugully and the

young Doual, who two years earlier had explored the Bong Bong area with his friend

Hamilton Hume. Throsby outlined the horrific treatment of Yelloming’s wife and children

that had occurred during earlier battles with settlers:

The people not content at shooting at them in the most treacherous manner in the dark, actually cut the woman’s arm off and stripped the scalp of her head over her eyes, and on going up to them and finding one of the children only wounded one of the fellows

deliberately beat the infant’s brains out with the butt of his musket, the whole of the bodies then left in that state by the (brave) party unburied!

Was it any wonder, Throsby asked, that the natives went looking for revenge? Yet Macquarie would tolerate no excuses:

The Aborigines, or native blacks of this country, having for the last three years manifested a strong and sanguinary hostile spirit, in repeated instances of murders, outrages, and depredations of all descriptions against the settlers and other white inhabitants residing

in the interior and more remote parts of the colony, notwithstanding their having been frequently called upon and admonished to discontinue their hostile incursions and treated on all these occasions with the greatest kindness and forbearance by government; – and having nevertheless recently committed several cruel and most barbarous murders on the settlers and their families and servants, killed their cattle, and robbed them of their grain and other property to a considerable amount, it becomes absolutely necessary to put a stop to these outrages and disturbances, and to adopt the strongest and most coercive measures to prevent a recurrence of them, so as to protect the European inhabitants in their persons & properties.

Macquarie ordered three separate military detachments to march into the ‘interior and

remote parts of the colony’ to punish ‘the hostile natives, by clearing the country of them

entirely, and driving them across the mountains; as well as if possible to apprehend the

natives who have committed the late murders and outrages, with the view of their being

made dreadful and severe examples of, if taken alive’.

I have directed as many natives as possible to be made prisoners, with the view of keeping them as hostages until the real guilty ones have surrendered themselves, or have been given up by their tribes to summary justice. in the event of the natives making the smallest show of resistance – or refusing to surrender when called upon so to do – the officers commanding the military parties have been authorised to fire on them to compel them to surrender; hanging up

on trees the bodies of such natives as may be killed on such occasions, in order to strike the greater terror into the survivors.

This is an extract from Macquarie by Grantlee Kieza. Published by HarperCollins and now available in all good bookstores and online.